Many of you may have heard of Hammurabi's "Law Code", often (incorrectly) called the earliest collection of laws recorded on a 4,000-year-old diorite monument.

But why is this incorrect, what is this extremely cool artefact about, and what do we still not know about it?

But why is this incorrect, what is this extremely cool artefact about, and what do we still not know about it?

The monument that records Hammurabi's Laws is not the earliest collection of legal provisions.

Three centuries earlier, during the best-documented period of history in ancient Iraq, a ruler named Ur-Nammu (or Namma) had laws written out in the Sumerian language.

Three centuries earlier, during the best-documented period of history in ancient Iraq, a ruler named Ur-Nammu (or Namma) had laws written out in the Sumerian language.

"If a man presents himself as a witness but is demonstrated to be a perjurer, he shall weigh and deliver 15 shekels of silver."

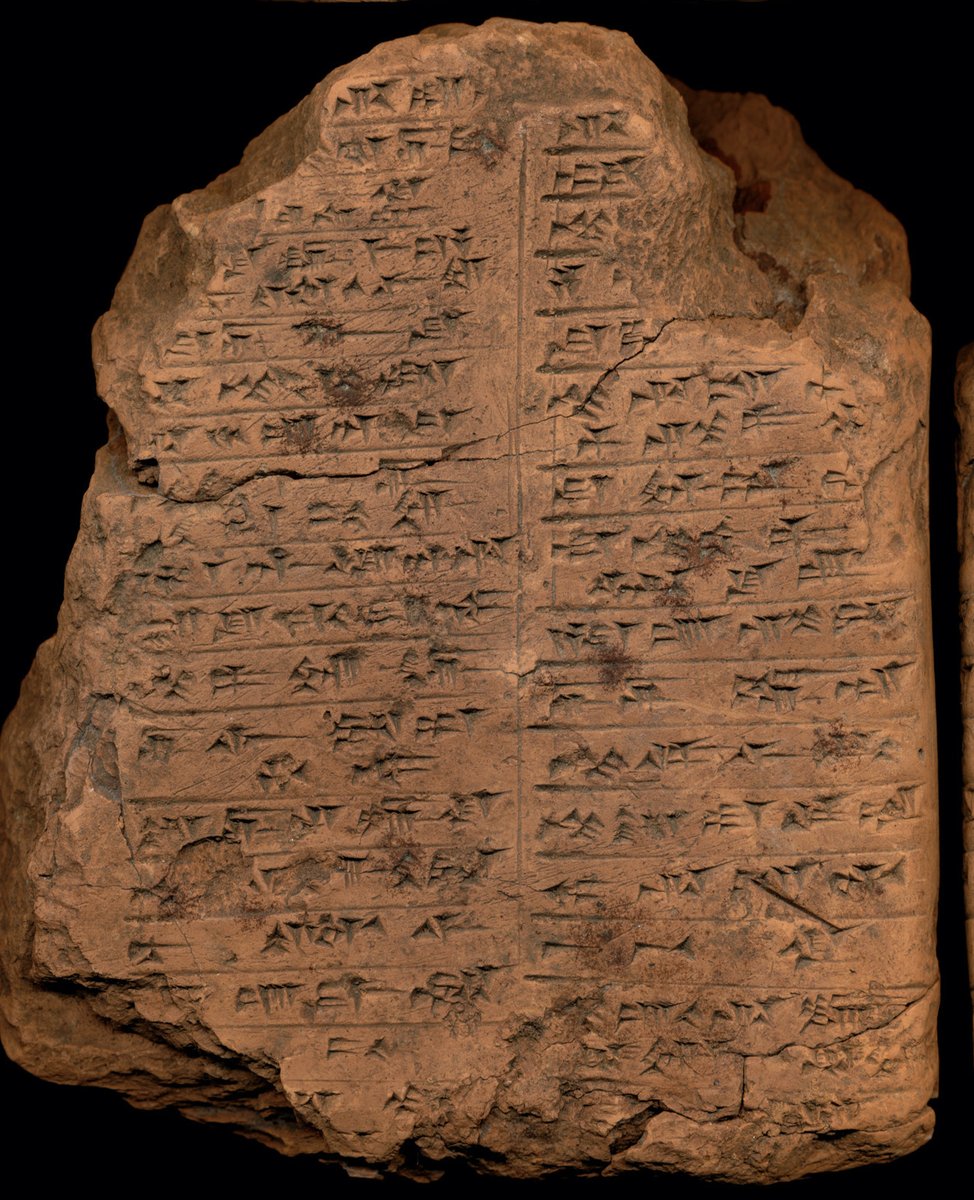

Written in Sumerian, the Laws of Ur-Nammu date to around 2100 BCE, but many have not survived.

Written in Sumerian, the Laws of Ur-Nammu date to around 2100 BCE, but many have not survived.

Collections of laws associated with other rulers before Hammurabi have survived from ancient Mesopotamia, and so too have school exercise texts with laws written on them.

This one was written by a scribal student named Belshunu

This one was written by a scribal student named Belshunu

Anyway back to Hammurabi. Or should I say…Hammurapi?

I don’t know, let's ask Prof. @SethLSanders about how to read his name based on the king's Amorite origins sethlsanders.wordpress.com/2019/11/14/ham…

I don’t know, let's ask Prof. @SethLSanders about how to read his name based on the king's Amorite origins sethlsanders.wordpress.com/2019/11/14/ham…

“If a man cuts down a tree in another man’s orchard without the permission of the orchard’s owner, he shall weigh and deliver 30 shekels of silver”

One of almost 300 laws written down on Hammurabi’s stela.

One of almost 300 laws written down on Hammurabi’s stela.

“If an awilum (a class of citizen) should blind the eye of another awilum, they shall blind his eye”

An articulation of “an eye for an eye” in Hammurabi’s collection of laws from the 18th century BCE.

An articulation of “an eye for an eye” in Hammurabi’s collection of laws from the 18th century BCE.

It’s even possible to learn something about physicians and medical “malpractice” in the 18th century BCE from Hammurabi’s Laws. Kind of.

I talk about that briefly about 10 minutes into this conversation with @pospo

I talk about that briefly about 10 minutes into this conversation with @pospo

The legal provisions recorded on Hammurabi’s monument cover ~so many~ scenarios. Marriage, divorce, illicit sex, false accusation, false testimony, grain storage, field usage, venture capital, kidnapping, theft, wet nursing, and much more.

The famous diorite stela is not the only source for Hammurabi’s collection of laws.

They were also copied down in scribal schools by students for over a millennium, which is a really long time and gives some important context for the production and use of the text.

They were also copied down in scribal schools by students for over a millennium, which is a really long time and gives some important context for the production and use of the text.

Hammurabi’s monument is not just a list of legal statements. It has a prologue and epilogue that highlight his achievements as king.

“In order that the strong not wrong the weak, to provide just ways for the hungry and widowed, I inscribed my precious pronouncements on my stela"

“In order that the strong not wrong the weak, to provide just ways for the hungry and widowed, I inscribed my precious pronouncements on my stela"

Here's the funny thing. One of the reasons Hammurabi’s Laws are so fascinating is that there’s almost no evidence they were enforced.

And if they weren’t enforced, then what on earth was the point of them?

And if they weren’t enforced, then what on earth was the point of them?

...If you want to learn more about Hammurab/pi and his laws, tune in this Friday when @AANDeloucas @SethLSanders @willismonroe Pamela Barmash, and I will discuss this fascinating text.

Open to all. Please join us! branecollective.org/2021/04/10/pri…

Open to all. Please join us! branecollective.org/2021/04/10/pri…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh