Today in pulp I'm looking at some of the many illustrators who worked for Ladybird Books.

The following thread may bring back memories...

The following thread may bring back memories...

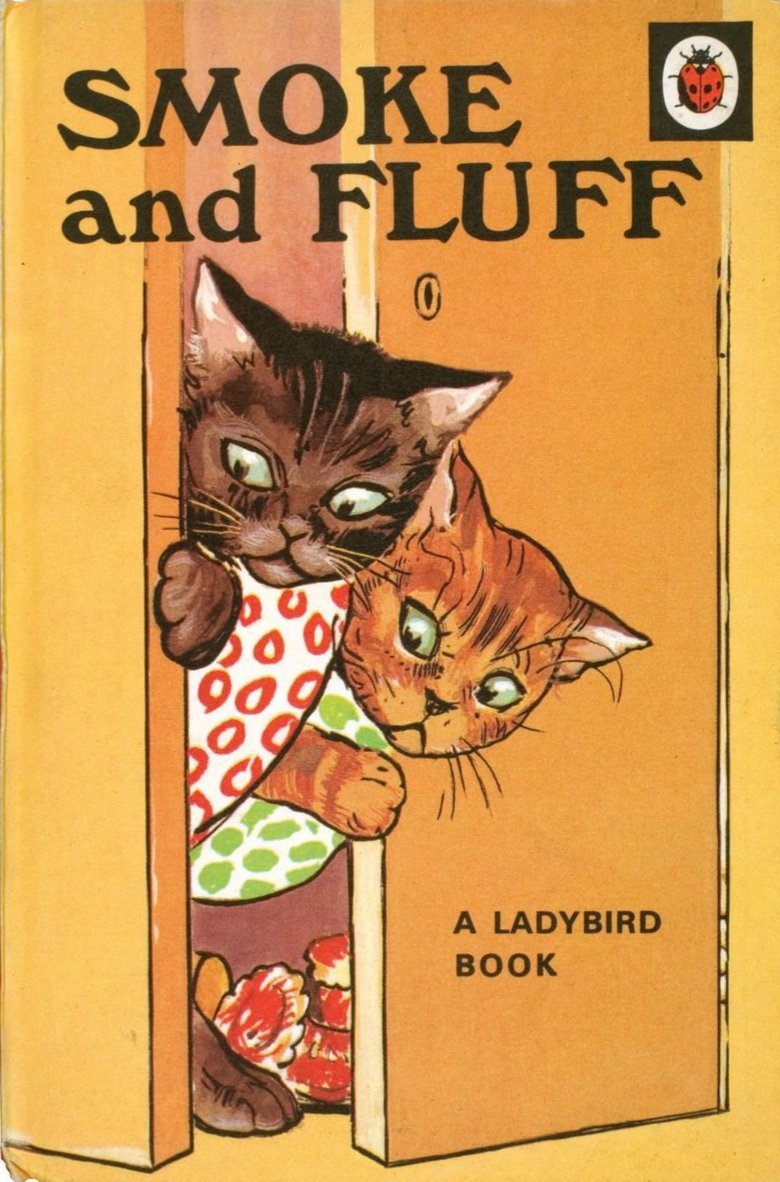

Ladybird Books began in 1914, but they really hit their stride from the 1940s onwards. Their distinctive hardback design with a bright, bold cover illustration made them hugely appealing to young readers.

Let's look at some of the people who helped make those iconic covers.

Let's look at some of the people who helped make those iconic covers.

Angusine Jeanne (A.J.) Macgregor illustrated many of the early Ladybird titles. She was born in Birmingham in 1879, where she later studied art before becoming a children's book illustrator. She began working for Ladybird in 1940.

As well as an illustrator A.J. Macgregor authored a number of children's stories. However her work for Ladybird consisted solely of illustrations, particularly for the Animal Rhymes series of verse stories by W. Perring.

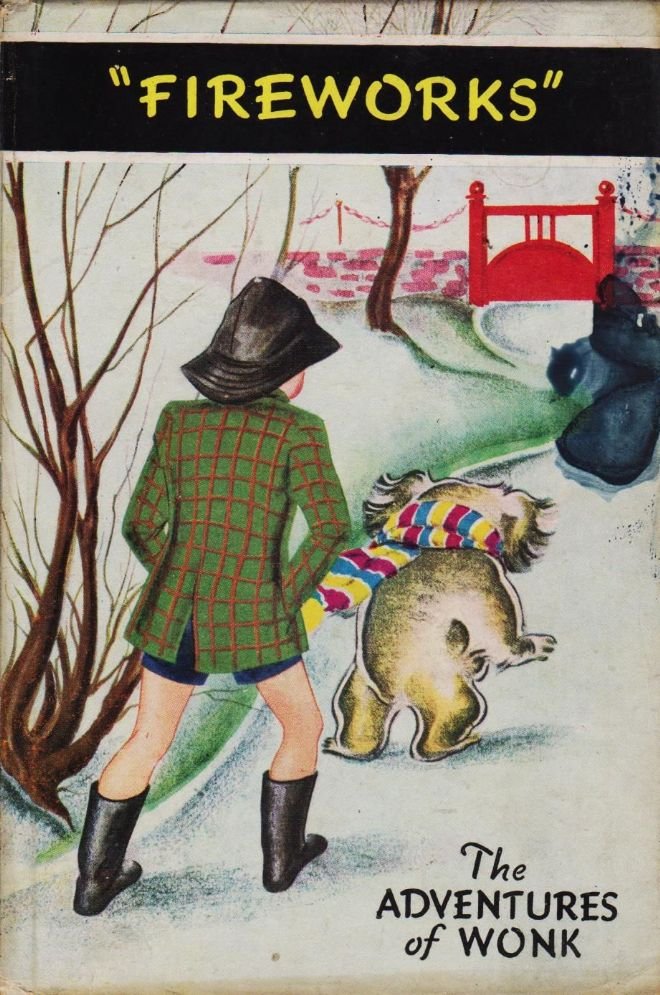

Joan Kiddell-Monroe was a prolific illustrator who is best known for her Oxford Myths and Legends series for OUP. However she also illustrated the Adventures of Wonk series for Ladybird in the 1940s.

Wonk was a mischievous koala who along with his friend Peter regularly got into trouble. These books are now quite rare as the wartime paper stock used for printing them was somewhat fragile.

Septimus Scott was born in Sunderland in 1879 and studied at the Royal College of Art before working in advertising. He is well known for his L&NER railway posters, but he also illustrated the 1950s Uncle Mac series of Ladybird stories.

Percy Bell Hickling had a long career in magazine illustration, drawing for Punch, Black and White and The Strand magazine in the 1920s and '30s. In 1949 he illustrated the Animal Tales stories for Ladybird Books.

Noel Barr wrote the Animal Tales series as a set of morality stories, with each animal having a habit or trait which they overcame. Ned The Lonely Donkey is probably the most famous book of the series and Hickling's full colour illustrations for it set a wonderful tone.

The Well Loved Tales series of Ladybird books was first published in 1964. Created as easy reading titles their covers were provided by two artists: Robert Lumley and Eric Winter.

Robert Lumley was born in London in 1920 and later set up Broad Oak Studios in Essex. He would often use local buildings and people as models for his work.

Eric Winter studied at Hornsey Art School before specializing in commercial art. As well as drawing for Eagle comic and Girl magazine he designed the Abbey National building society logo in 1950.

John Berry illustrated all 20 titles of the Ladybird People At Work range. Born in Hammersmith in 1920 he enlisted in the RAF at the start of WW2. His ability as a painter was quickly recognised and he became the only official War Artist to have been recruited from the ranks.

People At Work covered the main industries in Britain in the 1960s and '70s - from mining and railways to pottery and farming - as well as the uniformed services.

Ladybird produced a range of Bible Stories, which were staple reading at many a Sunday School. Kenneth Inns illustrated these in the 1950s with Clive Uptton working on the series in the 1960s.

History was certainly Ladybird's forte. Beginning in 1956 the Adventure From History range brought Kings, Queens, explorers and writers to life for many school children. John Kenny was the main illustrator for the early titles in this range.

Harry Wingfield worked across the full range of Ladybird books in the 1960s and '70s. His distinctive style is instantly recognisable and closely associated with Ladybird Books.

As is Martin Aitchison, who illustrated many of the Peter and Jane illustrations for the Key Word Reading Skills series. In fact I've barely scratched the surface of the many artists who have worked for Ladybird Books over the years.

If you want to learn more about the people behind Ladybird Books then you'll want to visit Ladybird Fly Away Home - one of the best fan sites available: ladybirdflyawayhome.com

That's it for my look at Ladybirds today. More another time...

That's it for my look at Ladybirds today. More another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh