Why are prescription drug prices so high in the US?

Let us start with insulin as an example. Insulin is the Achilles heel. If we understand insulin, we understand why it's so hard to fix our broken system.

1/ Existence of a vulnerable population needing a lifesaving medicine

Let us start with insulin as an example. Insulin is the Achilles heel. If we understand insulin, we understand why it's so hard to fix our broken system.

1/ Existence of a vulnerable population needing a lifesaving medicine

2/ Monopoly

3 companies control the market for insulin. In a monopoly with significant regulatory and legal barriers to entry of competing products, the seller can set the price however high they want.

Here, the monopoly is not over a luxury item, but a lifesaving medicine.

3 companies control the market for insulin. In a monopoly with significant regulatory and legal barriers to entry of competing products, the seller can set the price however high they want.

Here, the monopoly is not over a luxury item, but a lifesaving medicine.

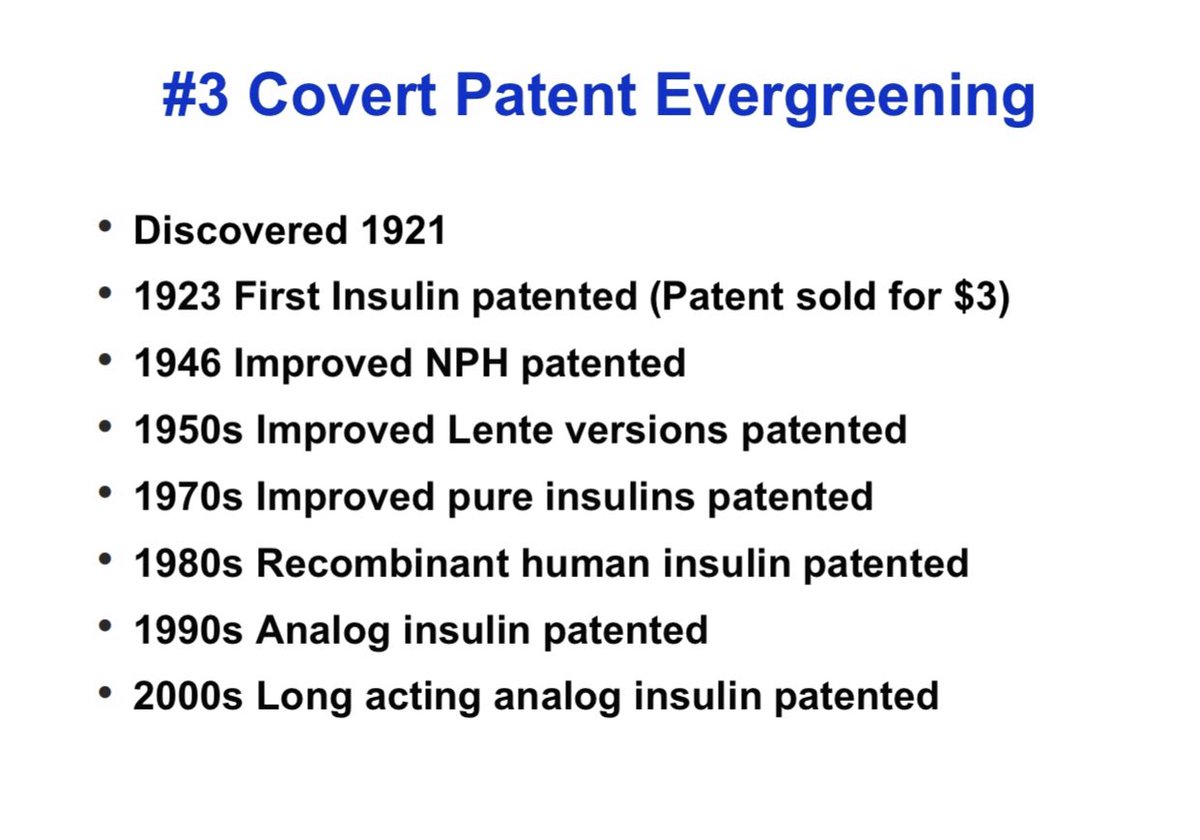

3/ Patent Evergreening:

Making patent life extremely long & preventing competition.

Covert: By making newer version of a drug and patenting it (see insulin below)

Overt: Filing multiple new patents on same drug to stretch patent life, pay for delay schemes, lawsuits.

Making patent life extremely long & preventing competition.

Covert: By making newer version of a drug and patenting it (see insulin below)

Overt: Filing multiple new patents on same drug to stretch patent life, pay for delay schemes, lawsuits.

4/ Planned Obsolescence

When Pharma introduces new drugs, the new one is marketed as so much better, that using an older drug is not good clinical practice.

With insulin it's ok. But in other fields, new "me-too" drugs often provide minimal incremental value to justify cost.

When Pharma introduces new drugs, the new one is marketed as so much better, that using an older drug is not good clinical practice.

With insulin it's ok. But in other fields, new "me-too" drugs often provide minimal incremental value to justify cost.

5/ Biosimilar and Generic drug approval process is slow, expensive, and complicated. Numerous regulatory and legal barriers.

Studies show you need 4 or more competing biosimilars/generics to have an effect on price. One is not enough.

Studies show you need 4 or more competing biosimilars/generics to have an effect on price. One is not enough.

6/ Price "Collusion"

Absent true completion, if just 2 companies make similar products they can choose to increase prices in lock step. Both benefit. With insulin for years prices of competing drugs increased almost on same day to same level. It is not overt collusion. But...

Absent true completion, if just 2 companies make similar products they can choose to increase prices in lock step. Both benefit. With insulin for years prices of competing drugs increased almost on same day to same level. It is not overt collusion. But...

7/ The Middlemen

Everyone in the supply chain from Pharma to Wholesaler to Pharmacy Benefit Manager to Pharmacy benefits from a higher price, except the patient. Profit is proportional to list price, which means it's in everyone's interest to have a high price.

Everyone in the supply chain from Pharma to Wholesaler to Pharmacy Benefit Manager to Pharmacy benefits from a higher price, except the patient. Profit is proportional to list price, which means it's in everyone's interest to have a high price.

8/ Influence of the Pharma Lobby

Pharmaceutical companies spend a lot on lobbying. Which is why nothing ever gets done.

Plus the factors for high price (#1-7) are many, and it's easy to point fingers.

Pharmaceutical companies spend a lot on lobbying. Which is why nothing ever gets done.

Plus the factors for high price (#1-7) are many, and it's easy to point fingers.

9/ There are also other factors that make prices insanely high that are unique to the US:

Medicare must buy, but cannot negotiate.

Prescribers of meds administered in doctors offices stand to gain more by prescribing a more expensive option.

Medicare must buy, but cannot negotiate.

Prescribers of meds administered in doctors offices stand to gain more by prescribing a more expensive option.

10/ So what are the solutions?

Every western nation has value based pricing. A maximum price that is negotiated for new drugs proportional to the value they provide. This ensures a reasonable launch price, & prevents the type of crazy price increases that are possible in the US

Every western nation has value based pricing. A maximum price that is negotiated for new drugs proportional to the value they provide. This ensures a reasonable launch price, & prevents the type of crazy price increases that are possible in the US

11/ Medicare must be able to negotiate for prices.

@ASlavitt once said almost 90% of Americans agree that Medicare should negotiate for drug prices, and 90% of Americans agree on very few things!

@ASlavitt once said almost 90% of Americans agree that Medicare should negotiate for drug prices, and 90% of Americans agree on very few things!

12/ Reform regulatory and patent process to make it easier for generics and biosimilars to end the market.

We cannot allow patent evergreening by repeated new patents filed on the same drugs as is the case with analog insulins and many new drugs.

We cannot allow patent evergreening by repeated new patents filed on the same drugs as is the case with analog insulins and many new drugs.

13/ Eliminate reimbursement for drugs administered in doctors offices from a % of sales price to a fixed reimbursement. The current system encourages the use of a more expensive alternative when an equivalent cheaper one is available.

14/ Reforms to ensure that price increases are not related to rebates and lack of transparency in deals between Pharma and PBMs.

Many ways to do this. Including transparency, ending practice of rebates or passing rebates to patients. There will be many trade offs. It's complex.

Many ways to do this. Including transparency, ending practice of rebates or passing rebates to patients. There will be many trade offs. It's complex.

15/ What can individual doctors do?

Help patients find the lowest cost options. Always prefer generics and biosimilars if possible.

For patients paying cash, prices of common drugs can vary dramatically. @GoodRx helps find the lowest price.

Help patients find the lowest cost options. Always prefer generics and biosimilars if possible.

For patients paying cash, prices of common drugs can vary dramatically. @GoodRx helps find the lowest price.

16/ Talk to patients about cost and affordability. Take cost and cost effectiveness into account when prescribing.

17/ I have discussed this in detail in a talk I gave @MayoClinic and you can access it here if interested. The problem of prescription drug prices is complex and unless we recognize the myriad factors and how they interact it is hard to fix.

cc: @hasanminhaj -- You have spoken about many of these issues on Patriot Act

My article on insulin pricing and what we can do about it. @MayoProceedings mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh