Just finished reading this book by Allen Parducci. I so loved it that I was sad approaching the end. In my experience it is very rare to find books that are very relevant to both your professional and personal life. I will summarize few takes below 1/n

The core question of the book is whether (and under which circumstances) a happy life is possible. Happiness is defined following utilitarianism as the summation of pleasure of pain over time. Parducci clearly states this definition is descriptive, rather than normative.

Parducci’s original hypothesis was that of an “equal balance”. He report the anecdote of his father explaining that he should not envy richer kids, as they must experience as much disappointment as other kids and are not necessarily happier.

Helson’s adaptation-level theory provided a scientific ground for this. It states that dimensional judgements depend on the difference between the stimulus value and the average (BTW this theory is also at the basis of the reference-point dependence of K&T's prospect theory)

Parducci sought to further test the theory to ultimately apply it to hedonic judgements, but he realized instead that Helson’s theory works well only in special circumstances (when stimuli are normally or uniformly distributed) and fails when stimuli distributions are skewed.

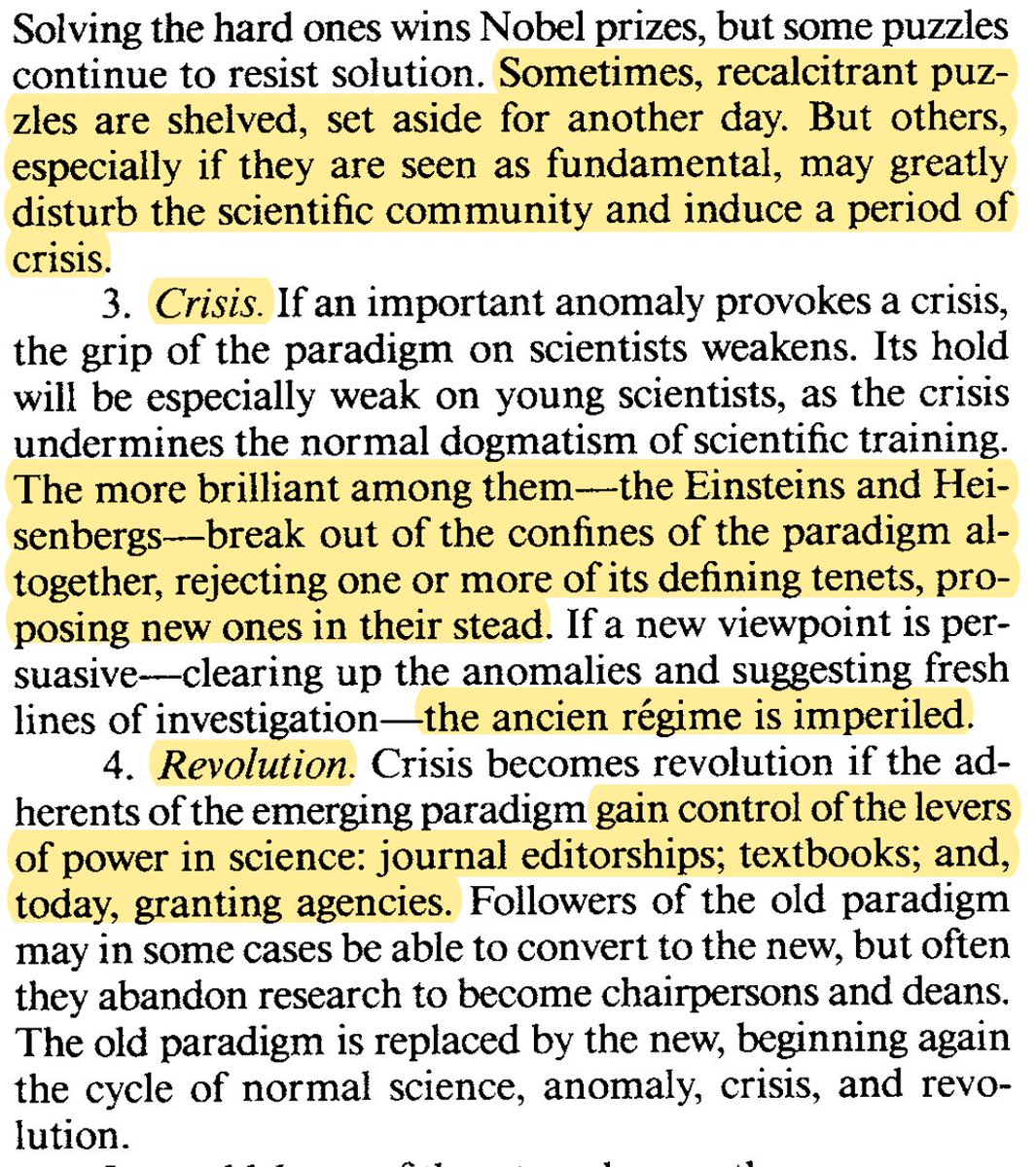

Indeed he finds that dimensional judgements are better explained by a compromise between the range value (the position relative to Smax and Smin) and the frequency value (essentially its normalized rank among all possible stimuli)

A key consequence of the R-F theory is that the average of judgements are no more doomed to strike "an equal balance". According to the R-F theory the average of judgements can be positive or negative as a function of the underlying distribution of the stimuli

Once applied to hedonic judgements, it appears that "happiness is a negatively skewed distribution" of hedonic experiences. The central part of the book is consecrated to showing how 1) apparently sensible choices can make us unhappy and 2) what we can do to tip the balance

Concerning 1: when we reach out for 'more' and we succeed, we experience immediate - reinforcing- satisfaction. However this new experience will extend our range upward, therefore undermining our subjective judgement of lesser results, that we once enjoyed

Concerning 2: letting go very high goals and expectations may counterintuitively tip the balance in favor of greater happiness (see the brillant figure below). Unfortunately it is easer to increase, than decrease, the range of contextual representations

In my opinion the book strikes a rarely achieved perfect balance between hard science, philosophy, phenomenology and real life anecdotes (from a guy who, en passant, co-invented the windsurf 🤯)surfertoday.com/windsurfing/th…

A final special mention for the thought-provoking chapter "utopia destroyed" where the effects of social planning of the US in Micronesia are seen through the critical lens of the R-F theory, highlighting the importance of psychological models of wellbeing for policy making.

If you don't want (or can't: I might have bought the last copy on Amazon: sorry 😬) read the book, I guess this article is a good summary of its main ideas psycnet.apa.org/record/1971-06…

I would like to conclude by mentioning a couple of "modern" development of the R-F theory

Kontek and Lewandowski range-dependent utility:

@RaBhui and @gershbrain DbS normative perspective: doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2…

Kontek and Lewandowski range-dependent utility:

@RaBhui and @gershbrain DbS normative perspective: doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2…

I wonder how the findings and hypotheses reported in the book relates to @RobbRutledge's recent more research on the determinant of momentary subjective well-being. Can the prediction error term of his equation capture range effects?

In case interested on why I was particularly excited by this book:

- I will present range effects on memory of economic values in this conference.

x.com/StePalminteri/…

- We recently published a paper (w/ @sophiebavard) on a pretty much related topic doi.org/10.1126/sciadv…

- I will present range effects on memory of economic values in this conference.

x.com/StePalminteri/…

- We recently published a paper (w/ @sophiebavard) on a pretty much related topic doi.org/10.1126/sciadv…

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh