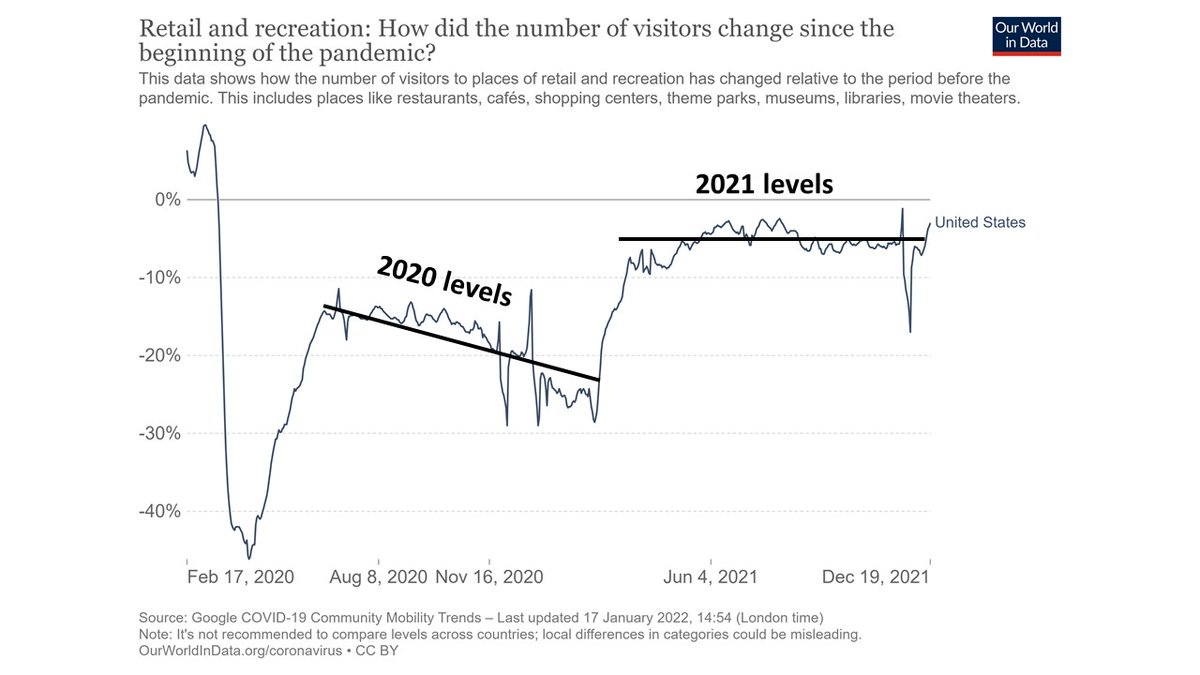

COVID rates are:

- declining in India, US, most of Europe

- stable & high in Latin America

- rising in sub-Saharan Africa & UK

Why such "random" waves of disease?

It's easy to blame variants, but this doesn't explain variability.

Segregated networks can explain five phenomena.

- declining in India, US, most of Europe

- stable & high in Latin America

- rising in sub-Saharan Africa & UK

Why such "random" waves of disease?

It's easy to blame variants, but this doesn't explain variability.

Segregated networks can explain five phenomena.

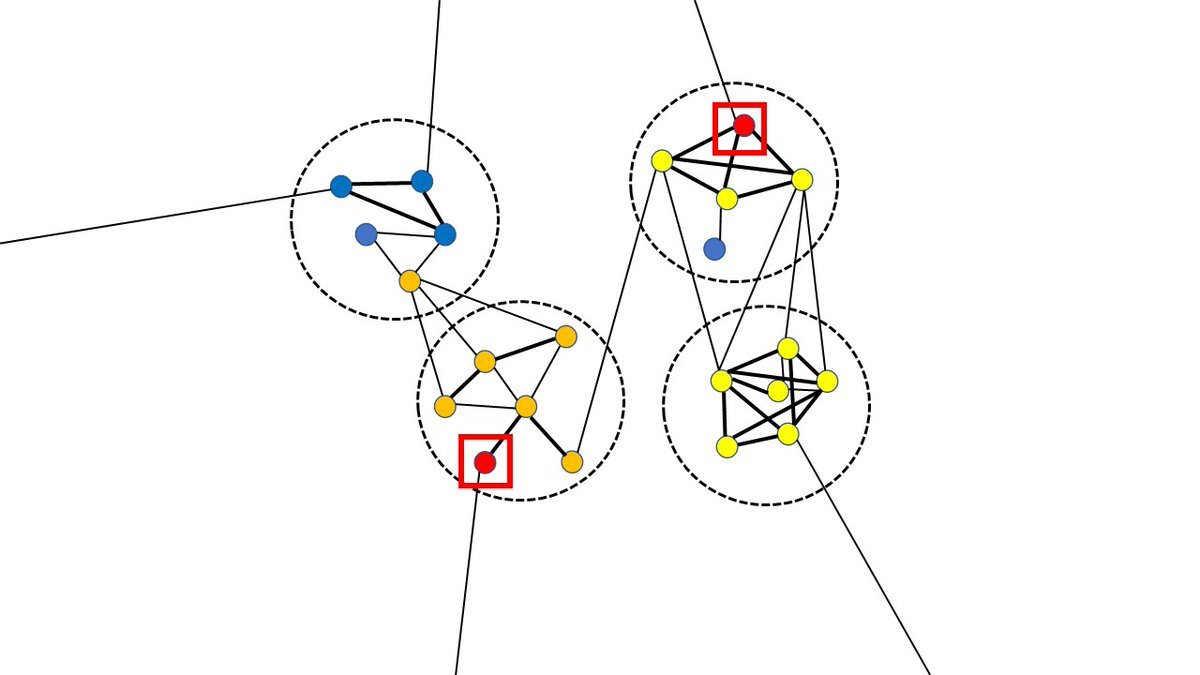

First, an orientation to this figure.

- Dot: person

- Dark line: very close contact (e.g., household)

- Light line: occasional contact

- Dotted circle: mini-network (e.g., same employer/school)

- Blue = uninfected, red = infected, orange = secondary infection, green = immune.

- Dot: person

- Dark line: very close contact (e.g., household)

- Light line: occasional contact

- Dotted circle: mini-network (e.g., same employer/school)

- Blue = uninfected, red = infected, orange = secondary infection, green = immune.

1. Small epidemics can occur without triggering a nationwide epidemic.

Say the person in the red square gets infected (via the line to the left). This will cause a micro-epidemic among their 2 close contacts, but might not spread.

Say the person in the red square gets infected (via the line to the left). This will cause a micro-epidemic among their 2 close contacts, but might not spread.

2. By contrast, if other people/groups are infected, major epidemics are likely to occur.

If either of the people in the red squares below get infected, then half the population will almost certainly get the disease.

But even major outbreaks may not infect the whole population.

If either of the people in the red squares below get infected, then half the population will almost certainly get the disease.

But even major outbreaks may not infect the whole population.

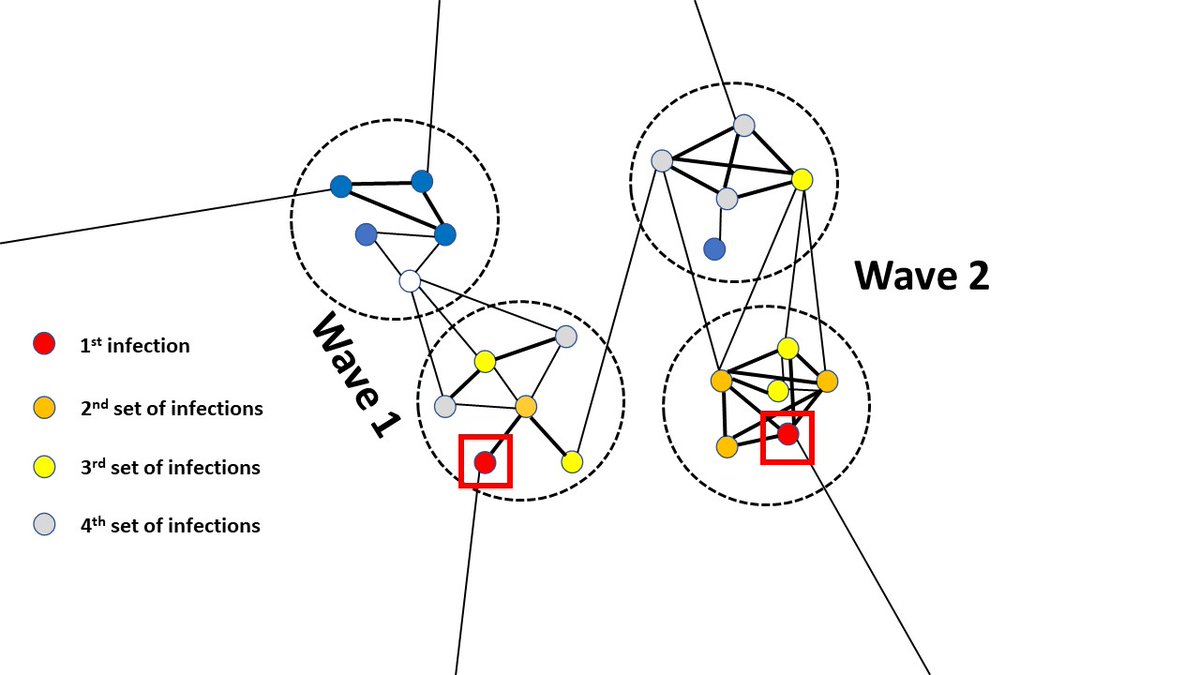

3. Epidemics can occur in waves at seemingly random times.

Say the person in the lower left is infected at one time, then the person in the upper right is infected later. This can trigger two independent waves b/c people on the left have few links w/ people on the right.

Say the person in the lower left is infected at one time, then the person in the upper right is infected later. This can trigger two independent waves b/c people on the left have few links w/ people on the right.

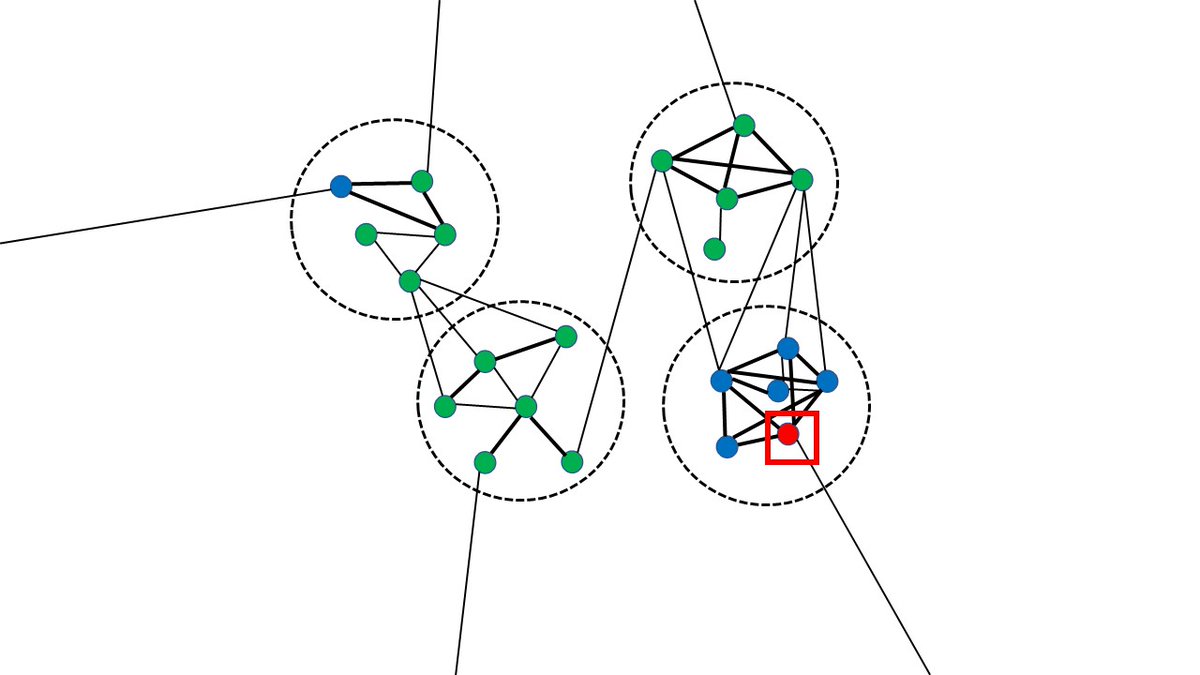

4. Outbreaks can still occur in populations where the majority of people are immune.

In the diagram below, ~70% of the population is immune (e.g., vaccinated or previously infected). Yet if the person in the lower right is infected, an outbreak will very likely occur.

In the diagram below, ~70% of the population is immune (e.g., vaccinated or previously infected). Yet if the person in the lower right is infected, an outbreak will very likely occur.

5. New waves can occur without new variants.

Assume the person in the lower left gets infected first, then the person in the lower right at a later time. The 1st wave will be slower, making the virus look less transmissible. But the only difference is the density of the network.

Assume the person in the lower left gets infected first, then the person in the lower right at a later time. The 1st wave will be slower, making the virus look less transmissible. But the only difference is the density of the network.

In summary, segregated networks can explain:

- small initial outbreaks

- the pandemic eventually reaching most places

- multiple epidemic waves at "random" times

- waves despite broad immunity (e.g., UK)

- waves of different size/speed

...without needing to invoke new variants.

- small initial outbreaks

- the pandemic eventually reaching most places

- multiple epidemic waves at "random" times

- waves despite broad immunity (e.g., UK)

- waves of different size/speed

...without needing to invoke new variants.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh