Today in pulp: how do you write a novel in two weeks?

Pulp writing that has to work within specific constraints, which in turn shape the nature of the story. And speed is the biggest constraint of all: you have to write quickly!

But there are ways to make it work for you...

Pulp writing that has to work within specific constraints, which in turn shape the nature of the story. And speed is the biggest constraint of all: you have to write quickly!

But there are ways to make it work for you...

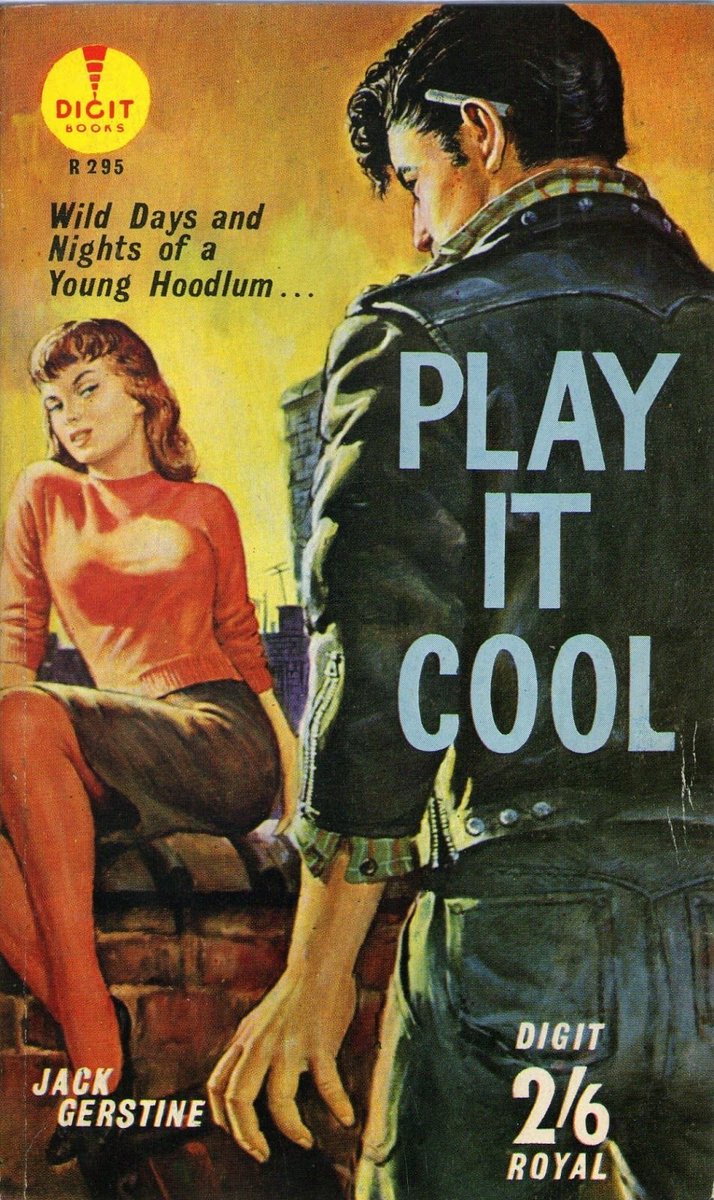

Today a prolific author may write a book every year, but in the 1950s and '60s pulp writer sometimes had as little as two weeks to complete a 50,000 word story and have it ready for print.

That’s 25 novels a year: but at least they got Christmas off!

That’s 25 novels a year: but at least they got Christmas off!

Writing that quickly is hard, but surprisingly liberating. Pulp writers had to go with their first ideas and had to make them work. There wasn’t time to ‘kill your darlings’ - instead you had to toughen them up and send them into battle!

But these books also had to sell. Potential readers had to see the book at the point of sale and immediately realise that this was something they would probably like. The plot, the characters, the themes all had to deliver immediate impact.

Pulp editors know their audience. They understand their passion points and their expectations. The pulp writer’s job is to hit those marks in spades, and to do it quickly, again and again. And there are certain hallmarks of pulp that make this frenetic writing process possible...

Full disclosure: a two week novel will not be a classic. There are many classic pulps but the following tips are not for writing those. However a two week novel is a fun writing exercise and will give you a break from crafting your Magnum Opus. It may even help it along a little.

Pulp hallmark no. 1 is: character comes through action. What a person does tells you who they are; you don’t need to go too deep into the character’s back-story to make them compelling. Think of a Clint Eastwood western. Do you know any of the background of The Man With No Name?

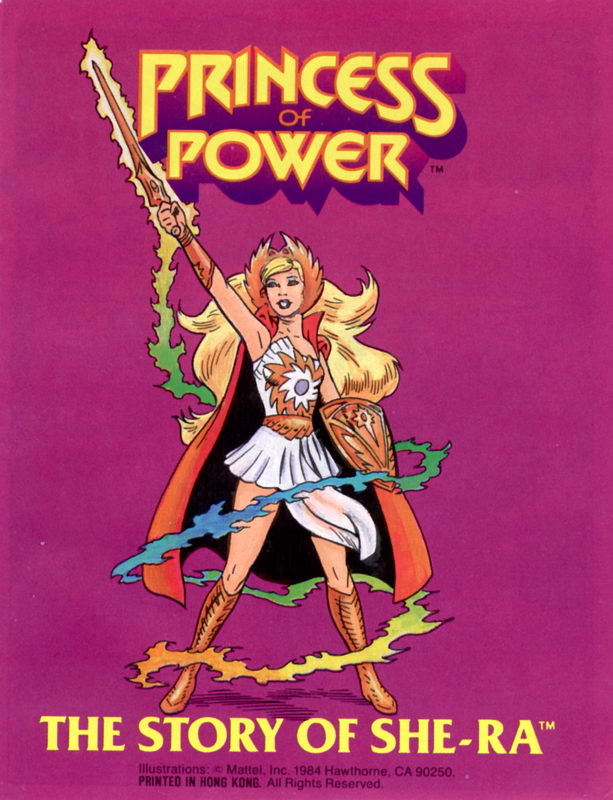

Well you don’t need to. Nor do you need to know Philip Marlowe’s back story, or what high school She-Ra attended. How they look, how they talk and what they do tells you everything you need to know to go with the character. The more they do, the more rounded they appear.

And that’s because pulp is not so big on character arcs. The character must have flaws and foibles, mannerisms and memorable tics, but they don’t need to be ‘on a journey.’ Or rather the journey itself is not one of personal growth…

Because the second pulp hallmark is: poetic justice. In a pulp story something is normally wrong with the world, some deep and possibly unspoken norm has been broken, and the hero’s job is to see that poetic justice is done to set things right.

Now the pulp hero lives within the moral confines of their particular world, even if they struggle with this fact. And in that world some things are just facts: the greedy win too often, the poor get shafted too much, love has too much cruelty about it, etc.

But even in that world some things just aren’t right. Some characters go too far, some people bite off more than they can chew, good people make bad choices. And it’s the hero’s job to be the agent of poetic justice, dragging things back to the (sometimes rotten) status quo.

Why do they do this? Because of pulp hallmark no. 3: they have a unique skill. Now that may be a practical skill: they’re an ace driver, a crack shot, or a demon lover. But it can also be intellectual: a forensic mind, an insatiable curiosity, a gambler’s instinct.

But the skill is always linked to a core belief, something the hero can never shake off. Someone has to stand up to bullies; someone has to protect the weak; revenge has to be served hot; mysteries have to be solved; soulmates can never be abandoned.

And they need one extra ingredient: insane levels of dogged persistance. Poetic justice means going through hell, and if you’re going through hell you have to keep going. In pulp the hero is always marching uphill and the hill keeps getting steeper and steeper.

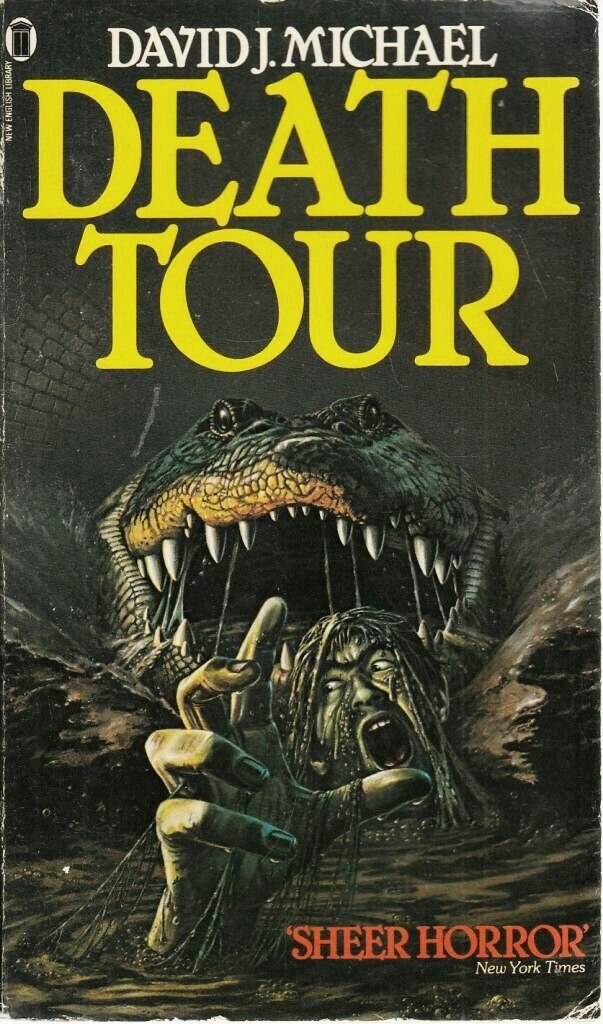

That’s because of pulp hallmark no.4: you keep shovelling grief onto the hero until you almost bury them! In most 3-act stories the dramatic tension rises and falls like a rollercoaster, with plenty of peaks and troughs until you reach the last thrilling section.

The pulp novel is a bit different. It tends towards an endless ratcheting up of the tension, problem after problem until the hero can barely stand. There’s no respite; the bad guys are getting nearer to them, the walls are moving closer, the storm is building…

The final scene is the moment of poetic justice: the showdown, the court scene, the villain’s unmasking, the lover’s salvation. Everything has been building to it and everything that has gone before is evidence for the moment of justice. We’re on tenterhooks awaiting the verdict.

Which leads to pulp hallmark no. 5: Deux Ex Machina is allowed! In pulp the Gods can intervene, fortune can alter the plot, a sudden inheritance can save the day. As long as it serves poetic justice, and happens at the right time to the right people, the audience will allow it.

A lightning bolt can burn down the castle. An eclipse can scare away the zombies. A lottery ticket can pay for the flight to Morocco to win back the long-lost sweetheart from the unscrupulous playboy. The Gods can and will intervene in pulp, and we the reader will cheer them on.

And this leads to pulp hallmark no.6: steal from the opera, not from the theatre. In opera the story is usually simple, because the passion and the drama is driven by the music.

But in theatre the story is more complex because the drama is driven by the dialogue. Pulp’s great trick is to lean towards the operatic, rather than the theatrical, to push the novel forwards.

Raw emotion, impulsive action, moments of great terror and pity: these are the operatic hooks of pulp. So give a character a moral problem, let the suffer as they gather the evidence, then let poetic justice be served!

3,600 words a day for 2 weeks. No rewrites. See how you go.

3,600 words a day for 2 weeks. No rewrites. See how you go.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh