Jews used many surfaces to write incantations in late antiquity.

Two of the more well known & preserved kinds are earthenware bowls & metal amulets. In Babylonia, we only have evidence of the former.

However, other surfaces were used, like skulls and eggshells! 💀🥚

🧵 1/9

Two of the more well known & preserved kinds are earthenware bowls & metal amulets. In Babylonia, we only have evidence of the former.

However, other surfaces were used, like skulls and eggshells! 💀🥚

🧵 1/9

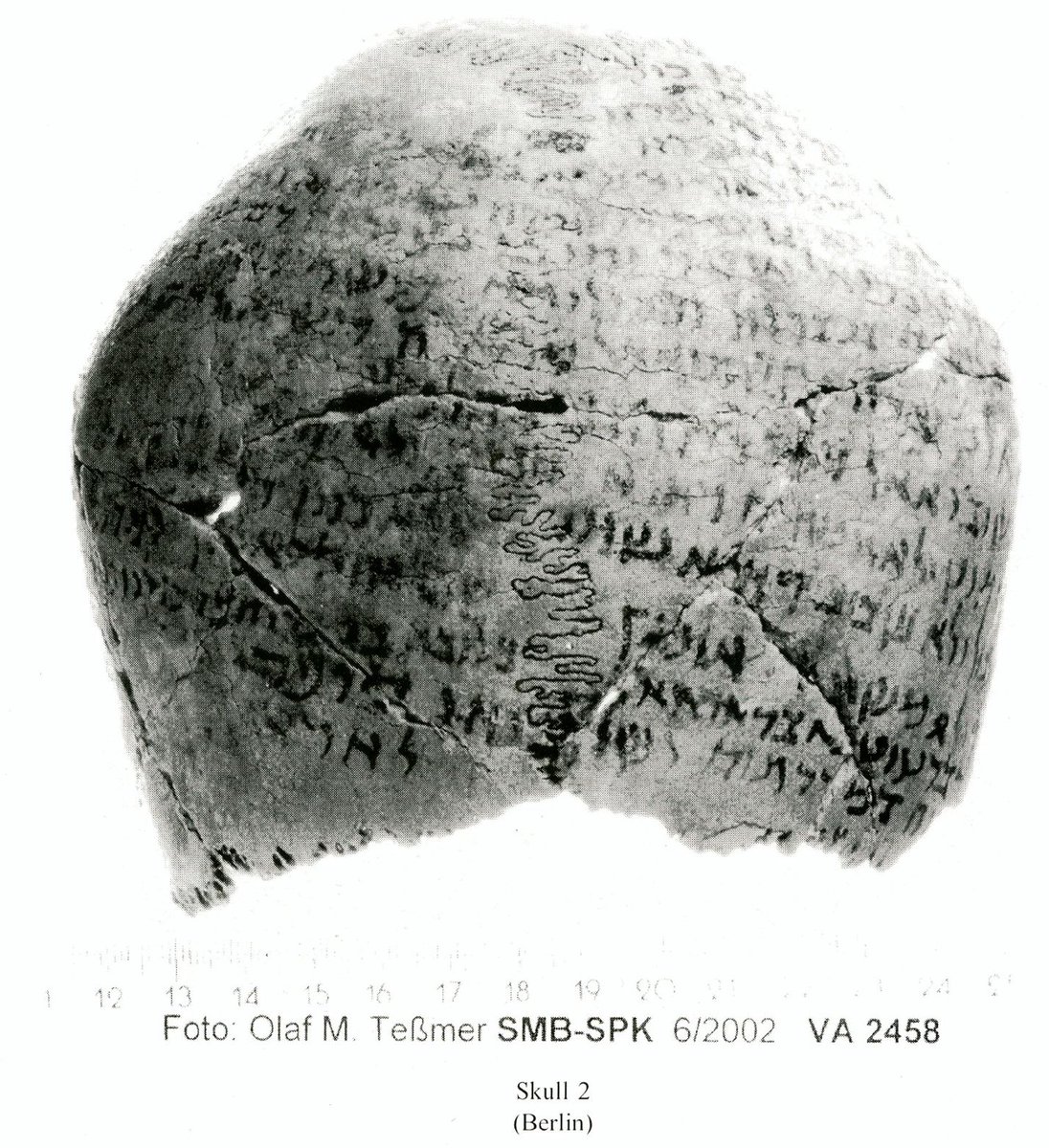

Five Jewish Babylonian Aramaic skull incantations are currently known, both male and female.

They have all been expertly examined and published by Dan Levene here:

academia.edu/3692177/Levene….

2

They have all been expertly examined and published by Dan Levene here:

academia.edu/3692177/Levene….

2

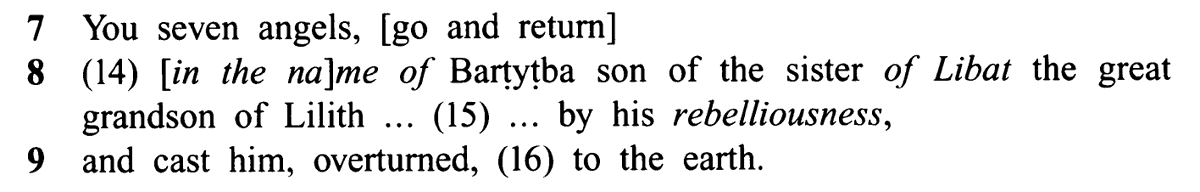

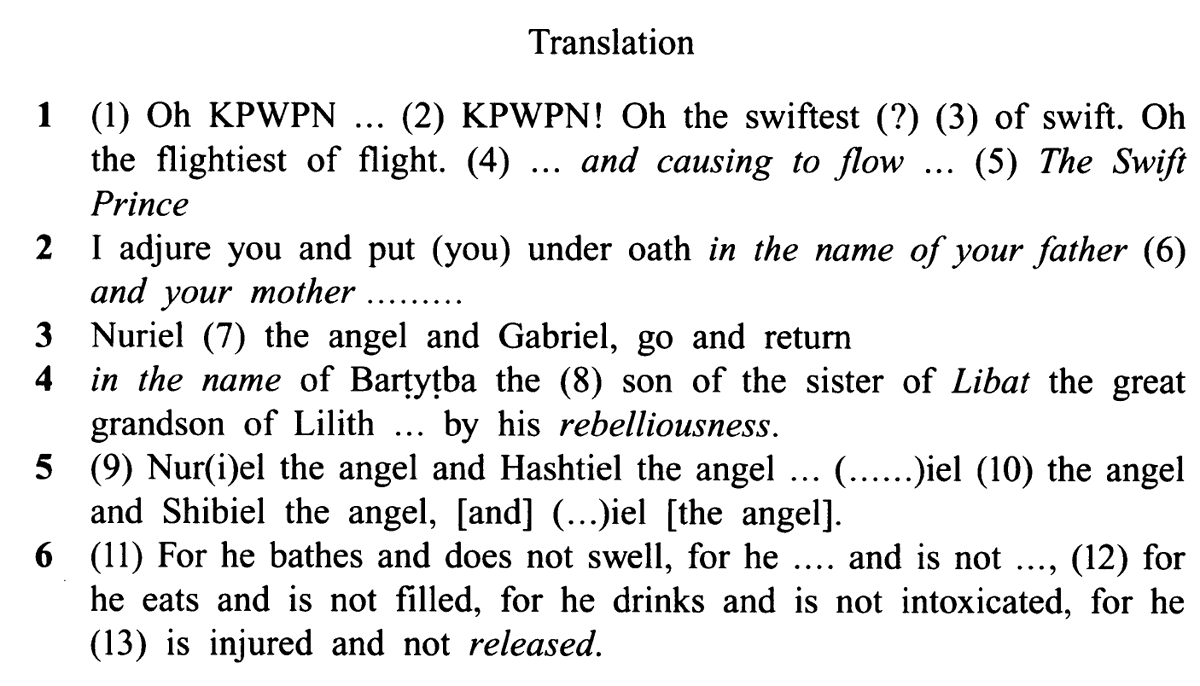

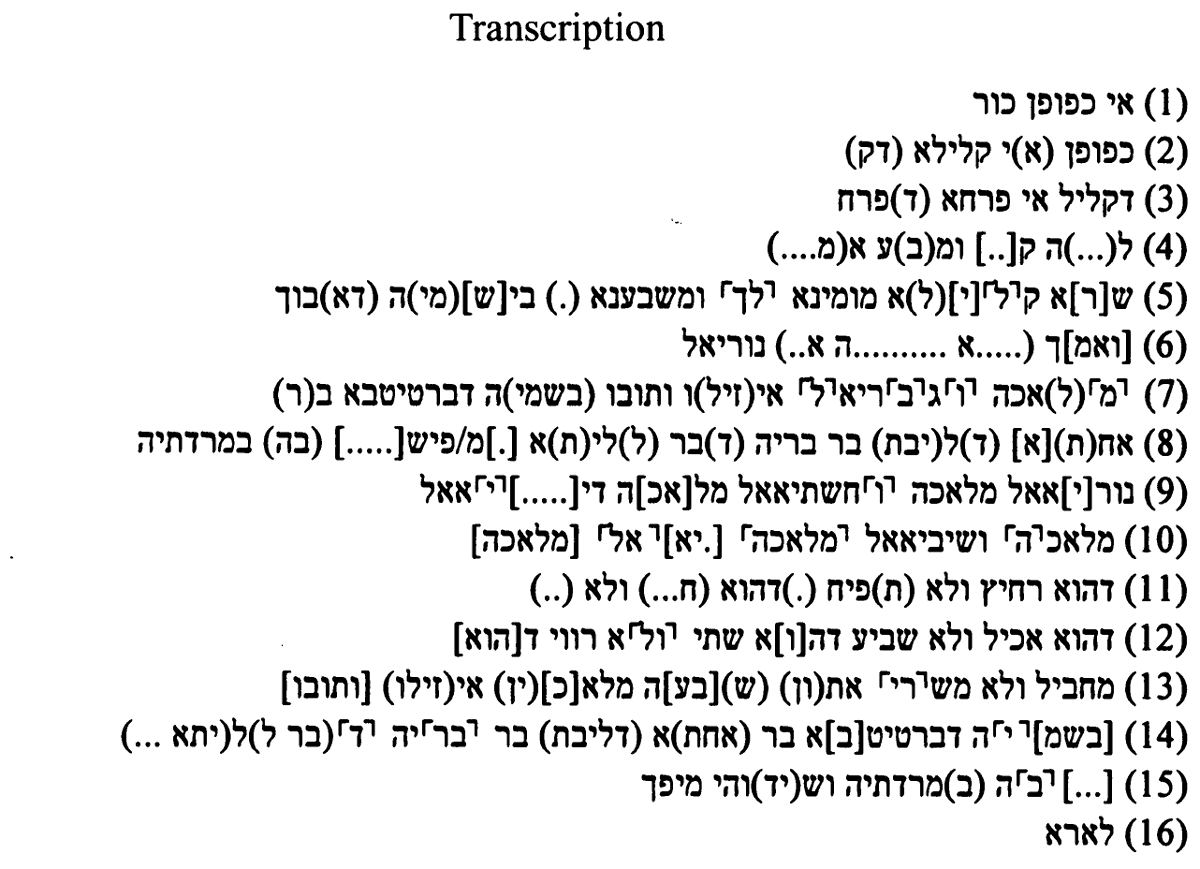

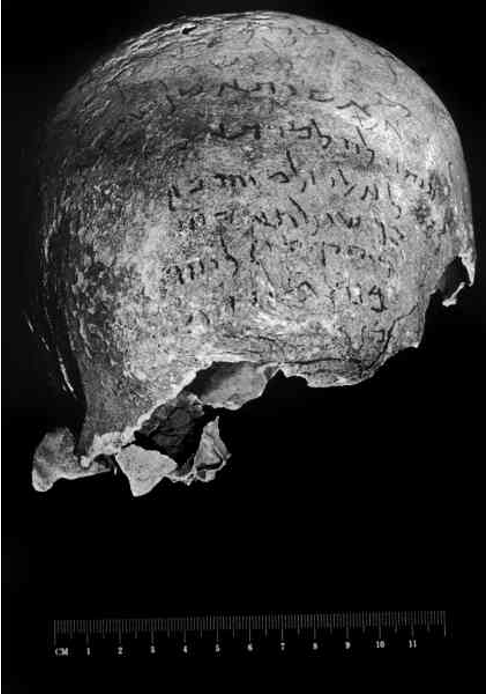

The incantations on the skulls are preserved to different degrees.

Two are highly fragmentary, and one is written in pseudo-script, that is, there is no legible incantation.

But two contain incantations parallel to those on incantation bowls. Here is the most complete one:

3

Two are highly fragmentary, and one is written in pseudo-script, that is, there is no legible incantation.

But two contain incantations parallel to those on incantation bowls. Here is the most complete one:

3

Why skulls? How common was this?

It's difficult to say.

It should be noted that a number of archaeological reports describe the discovery of bowls in/ near cemeteries.

Cemeteries and the dead were probably viewed as sites where otherworldly power was more easily exploited.

4

It's difficult to say.

It should be noted that a number of archaeological reports describe the discovery of bowls in/ near cemeteries.

Cemeteries and the dead were probably viewed as sites where otherworldly power was more easily exploited.

4

Jewish magical recipe books discuss the use of bones, like the Babylonian "Sword of Moses":

To send a spirit, take a bone of a dead man & the dust from under it with a tooth & tie it up in a colored linen rag, & say upon it from..to..in his name, & bury it in the cemetery."

5

To send a spirit, take a bone of a dead man & the dust from under it with a tooth & tie it up in a colored linen rag, & say upon it from..to..in his name, & bury it in the cemetery."

5

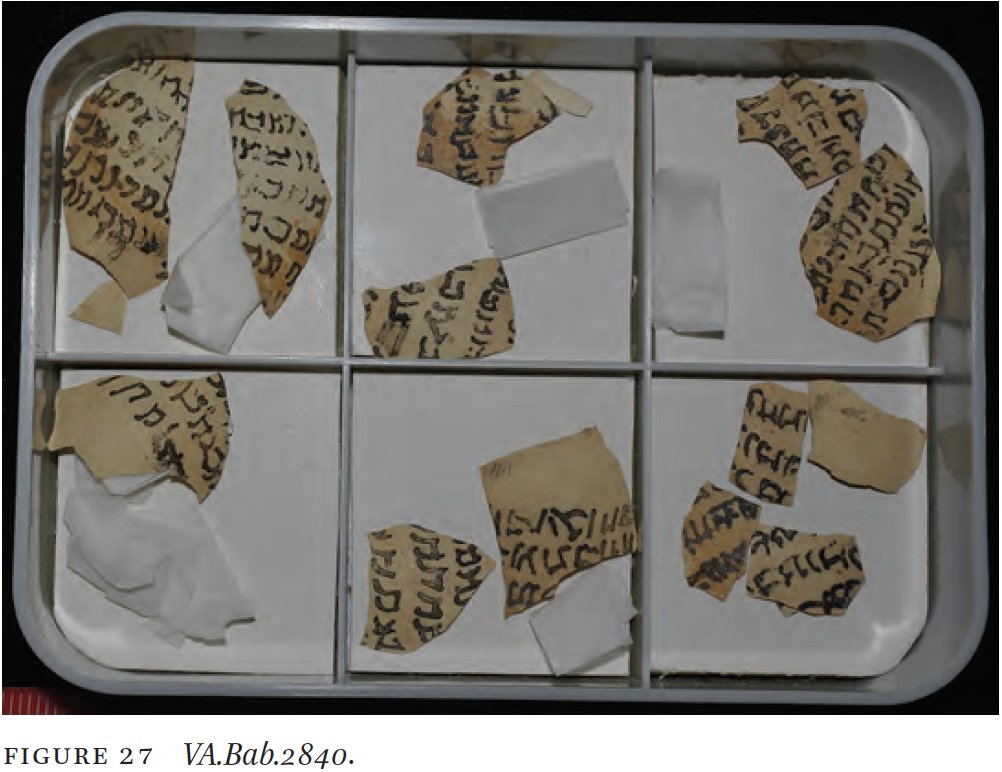

Other surfaces used include eggshells, and these are more common than skulls.

A number of these are associated with love magic in particular, wonderfully analyzed by Ortal-Paz Saar in her book on Jewish love magic.

6

A number of these are associated with love magic in particular, wonderfully analyzed by Ortal-Paz Saar in her book on Jewish love magic.

6

For whatever reason, these are always chicken eggs.

Love spells try to make the target "burn" with love for the client, and therefore via the logic of sympathetic magic, the eggs with incantations were often tossed in flames to enact that burning.

7

Love spells try to make the target "burn" with love for the client, and therefore via the logic of sympathetic magic, the eggs with incantations were often tossed in flames to enact that burning.

7

For instance, one such spell reads:

"Take an egg that was born on Thursday from a black hen & bake the egg, & remove its upper shell, & write on the egg 'dwng dg dwng', & burn it, & say: ‘As this egg is burning so should burn the heart of n {son} daughter of n over the land."

8

"Take an egg that was born on Thursday from a black hen & bake the egg, & remove its upper shell, & write on the egg 'dwng dg dwng', & burn it, & say: ‘As this egg is burning so should burn the heart of n {son} daughter of n over the land."

8

Magical recipe books include a number of other surfaces and materials used for writing or effectuating amulets, but we have yet to discover material evidence of their use. But that may change at any moment!

Fin.

9/9

Fin.

9/9

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh