So, Homo longi. It's such a good name. Dragon people. And an amazing skull discovery. Adds to our knowledge of the Middle Pleistocene in China. But it's sad that the name is not going to stay. cell.com/the-innovation…

The boring reason why we can't use the Homo longi name is technical. The research puts the Harbin skull together with the Dali skull, and Xinzhi Wu gave that the name Homo sapiens daliensis more than 40 years ago. So IF there's a species, it has to be H. daliensis.

In case you wonder how close Harbin looks to Dali, here is Harbin on the left and Dali (which has some crushing to the maxilla) on the right. As Weidenreich might have said, they resemble each other as closely as one egg resembles another.

But technical problems are unsatisfying. The real question is whether the Chinese later Middle Pleistocene record represents a lineage, and whether we should consider such lineages, like Neandertals, as species. Are Homo daliensis and Homo neanderthalensis the right way to talk?

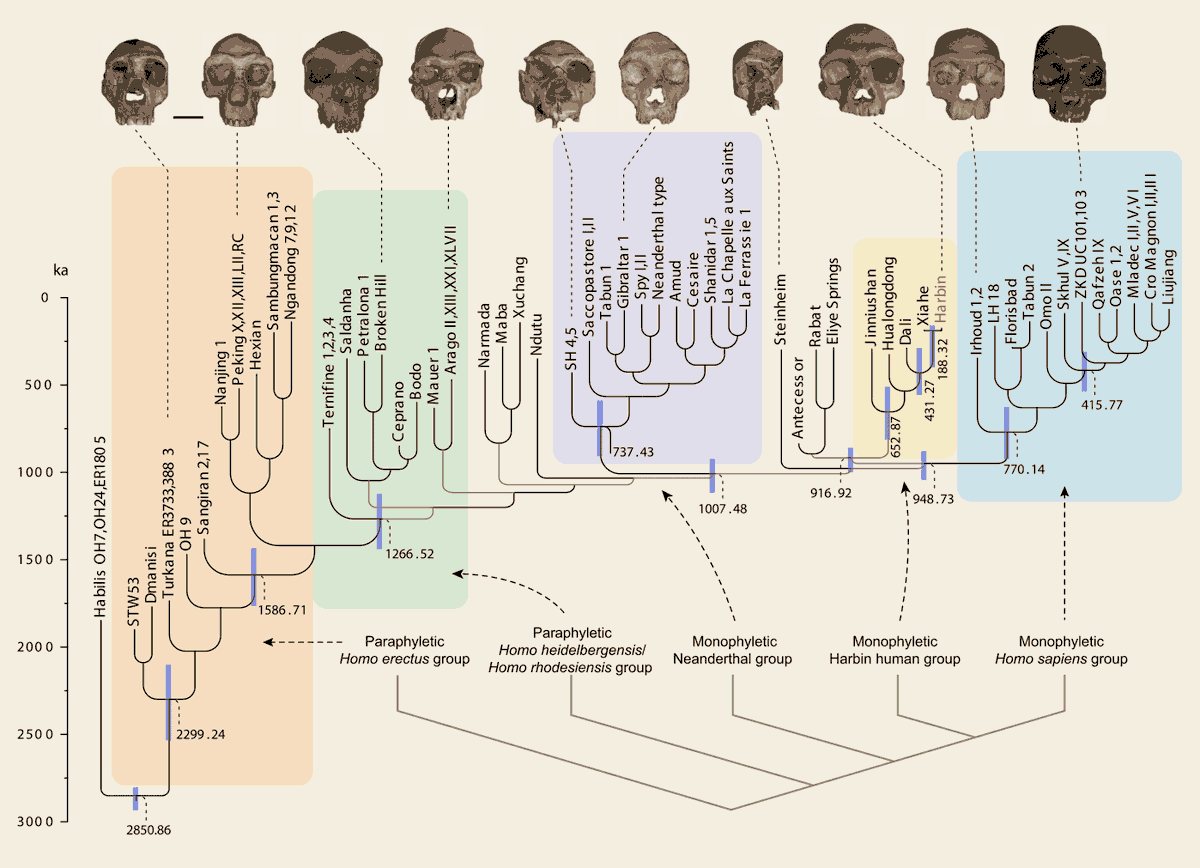

This is a deep problem upon which scientists have diverse opinions. I think that this new research on the Harbin fossil offers a window to a clearer future. Let's take a close look at that phylogeny, the one that places the Chinese MP fossils close to African H. sapiens...

The actual branch patterns are fascinating. H. antecessor groups with the Jinniushan-Dali-Harbin-Xiahe clade. Neandertals are an outgroup to these and moderns. Modern humans and H. antecessor are sister clades to the exclusion of Neandertals! It's nuts!

Now, we have learned a few things from DNA and ancient proteins. H. antecessor is a sister of the Neandertal-Denisovan-modern clade. Neandertals, today's humans, and Denisovans share common ancestors around 700,000 years ago. Neandertals and Denisovans were related.

All known archaic groups with ancient DNA evidence interbred. Repeatedly. Seemingly every time they came into contact. Three distinct groups of Denisovans, all known from their ancient interbreeding with modern people. So. Much. Interbreeding.

We have the interesting question of whether the Harbin skull is a Denisovan. Dali, Jinniushan, Hualongdong, all Denisovans. Good hypothesis. Could be true. Knowing the answer, though, is not essential to the basic problem, which is: Morphology and DNA here are inconsistent.

There is no way to make this tree match what we know from DNA and protein. Neandertals are in the wrong place. H. antecessor is in the wrong place. Heck, even Liujiang and ZKD Upper Cave seem like they're in the wrong places. Morphology and DNA are inconsistent.

It's not a question of DNA being right and morphology being wrong. They just tell us about different things. Morphology tells us about adaptation, convergence, and retained features from deep ancestors. DNA tells us about phylogeny, incomplete lineage sorting, and introgression.

So are they species? I think that the appearance of morphological distinctiveness between these human groups is mostly a result of poor sampling. This new research shows that as we increase the sample, our picture gets blurrier and less likely to match DNA evidence of phylogeny.

We still have much to do to understand why lineages retained some genetic differentiation for hundreds of thousands of years, and we may yet find that speciation mechanisms such as fitness costs of hybridization may be a part of the explanation. But we're not there yet.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh