Routines redeploy attention

→ They enable students to spend less time thinking about the *process* of their learning and more time thinking about the *content* of their learning.

🧵...

→ They enable students to spend less time thinking about the *process* of their learning and more time thinking about the *content* of their learning.

🧵...

First, let's zoom out a bit. Routines can be both behavioural and/or instructional:

• Behavioural routines (eg. classroom entry) create more time and space for learning.

• Instructional routines (eg. cold call) make learning more efficient.

• Behavioural routines (eg. classroom entry) create more time and space for learning.

• Instructional routines (eg. cold call) make learning more efficient.

Both types bring a range of benefits:

→ Reduction in behaviour management burden

→ Increased student motivation, confidence and safety

→ Freeing up of teacher mental capacity to monitor learning and be more responsive

→ Reduction in behaviour management burden

→ Increased student motivation, confidence and safety

→ Freeing up of teacher mental capacity to monitor learning and be more responsive

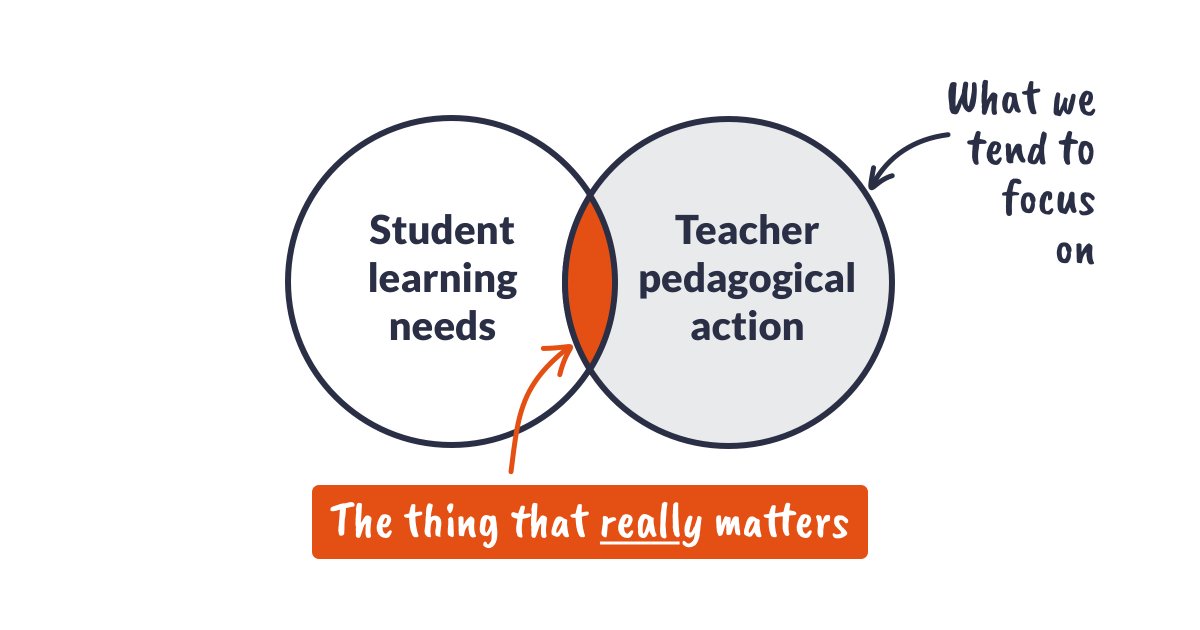

But imho the main benefit is how they shift the balance of attention:

Routines enable students to spend less time thinking about the *how* of their learning, so they can spend more time thinking about the *what* of their learning ⚖️

Routines enable students to spend less time thinking about the *how* of their learning, so they can spend more time thinking about the *what* of their learning ⚖️

They do this by stripping out decision costs, reducing the amount of novel information that needs to be processed, and employing our ability to think less about the things we repeatedly do.

They hack the attention economy of the classroom to help pupils learn things faster.

They hack the attention economy of the classroom to help pupils learn things faster.

Routines are often thought of as boredom-brokers and creativity-killers, but I'm not sure this is always true...

→ Effective routines can secure success and so act as an antidote to boredom.

→ They also free up the precious mental capacity needed for creativity to flourish.

→ Effective routines can secure success and so act as an antidote to boredom.

→ They also free up the precious mental capacity needed for creativity to flourish.

Caveat: I'm not saying that lessons should be formulaic.

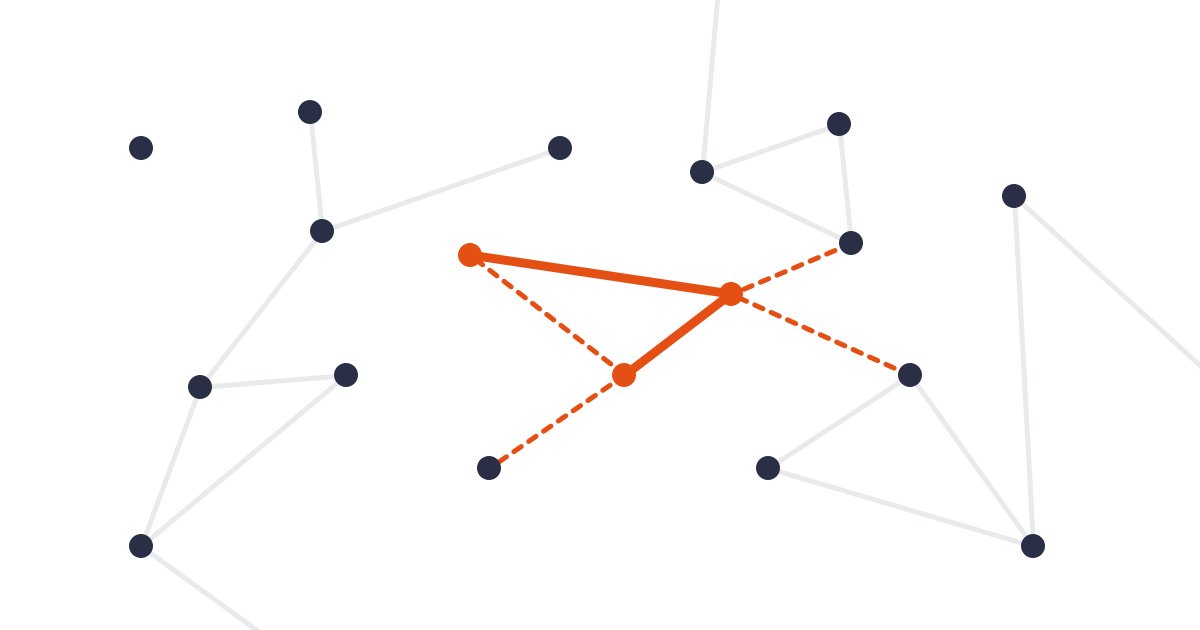

Instead, I find it more useful to think about having a broad 'repertoire of routines' to draw upon.

This ensures that teaching can be both efficient *and* responsive: to help meet the needs of students and the curriculum.

Instead, I find it more useful to think about having a broad 'repertoire of routines' to draw upon.

This ensures that teaching can be both efficient *and* responsive: to help meet the needs of students and the curriculum.

Finally, for any PD folks who've made it this far:

A reminder that teaching teachers is just teaching: routines can be also be powerful in a PD context.

This is why instructional coaching has such potential: as a finely-tuned routine for ongoing teacher development.

A reminder that teaching teachers is just teaching: routines can be also be powerful in a PD context.

This is why instructional coaching has such potential: as a finely-tuned routine for ongoing teacher development.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh