Wooden tablets found on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the 19th century, thought to display writing or proto-writing. Never deciphered, since the native Rapa Nui said they couldn't read them when asked by the 19th century Europeans.

The first European to notice them was Eugène Eyraud in 1864, a friar stationed on Rapa Nui to proselytize. He reported seeing hundreds of tablets, but 4 years later, a French priest tried to recover as many as possible, and could only find a few.

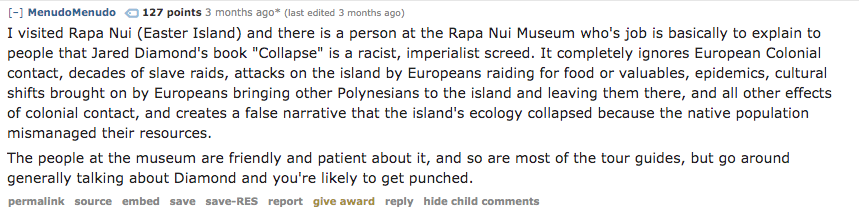

Their disappearance might be explained by reports of the native Rapa Nui's apparent disinterest in their survival. This is perhaps connected to European-introduced diseases to the island and the brutal Peruvian slave trade. These might have killed all the literate Rapa Nui.

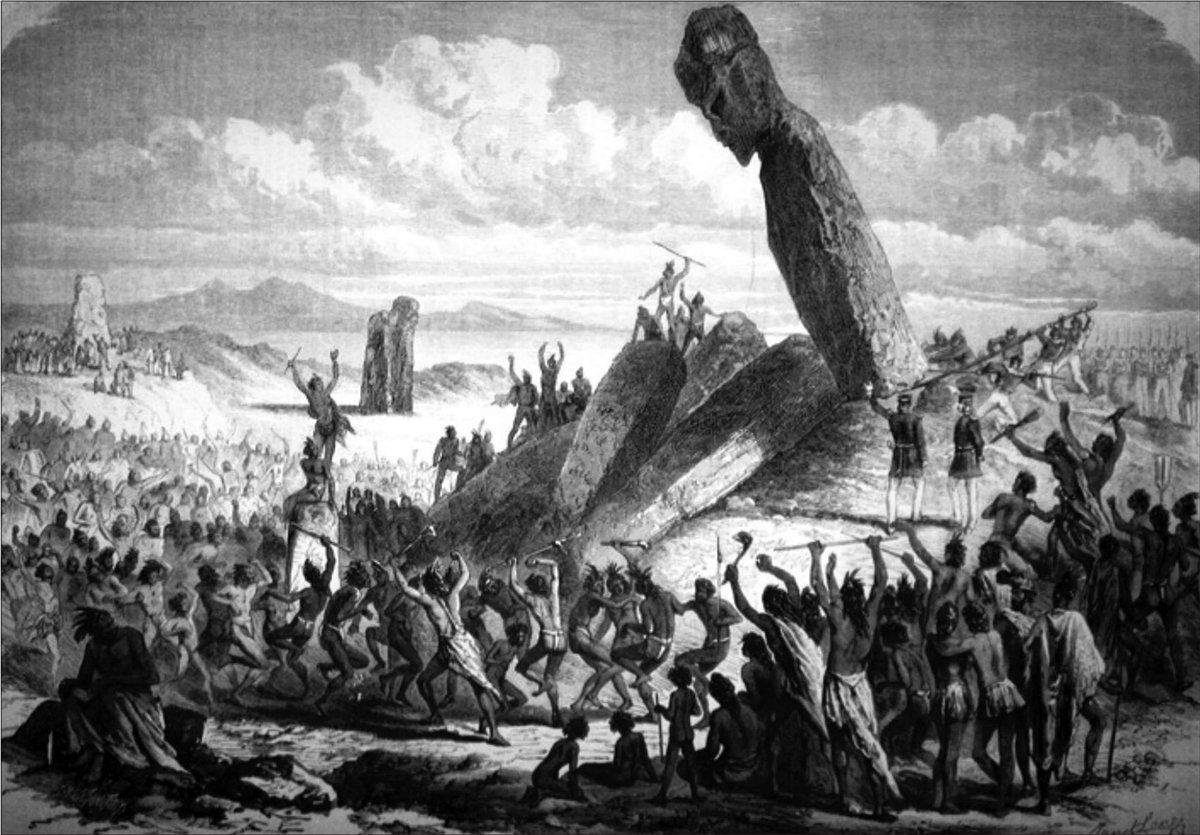

Rapa Nui also has tons of petroglyphs, the most in Polynesia. "Nearly every suitable surface has been carved." However, there seems to be limited connections between the petroglyphs and the tablets; the petroglyphs aren't "text-like."

Only about 2 dozen of the tablets remain, none on the island, all scattered through museums and private collections.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

![The late-Ming master of literati Dong Qichang if;lt~ (1555-1636) commented on the relationship between nature and painting, as quoted and translated by James Cahill: 'From the standpoint of splendid scenery, painting cannot equal [real] landscape. But from the standpoint of the sheer marvels of brush and ink, [real] landscape is not at all the equal of painting.'1 This early-seventeenth-century remark about Chinese landscape painting demonstrates the mutually irreplaceable status of nature and painting as reflected in contemporary artistic discourse. However, in the European Renaissance, Le...](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GfB_i1tbcAALSnz.jpg)