In 1836, British artist Frederick Catherwood met American travel-writer John Lloyd Stephens in London. They had read about some mysterious ruins discovered recently in Central America, so, in 1839, they set off on an expedition. [1/6]

This is perhaps the only picture we have of Catherwood (left, Stevens right). He died in 1854 when the steamer he was on collided with a French ship in the north Atlantic. He didn’t even appear on the casualty list (until friends and family kicked up a fuss). [2/6]

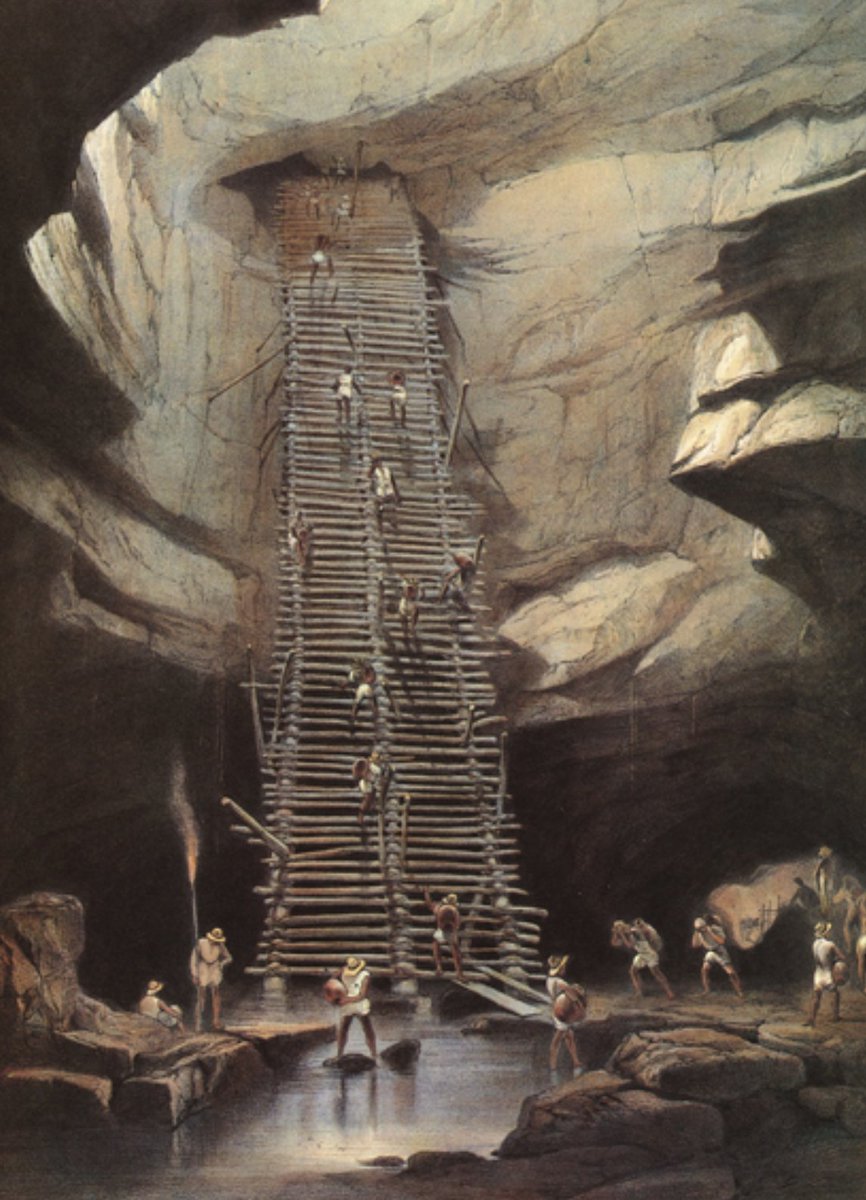

Catherwood had been sketching Mediterranean architecture for years, and, upon reaching central America, he declared that the structures they saw bore no similarity (and were therefore made by native Americans!). He drew these at Copán, Honduras. [3/6]

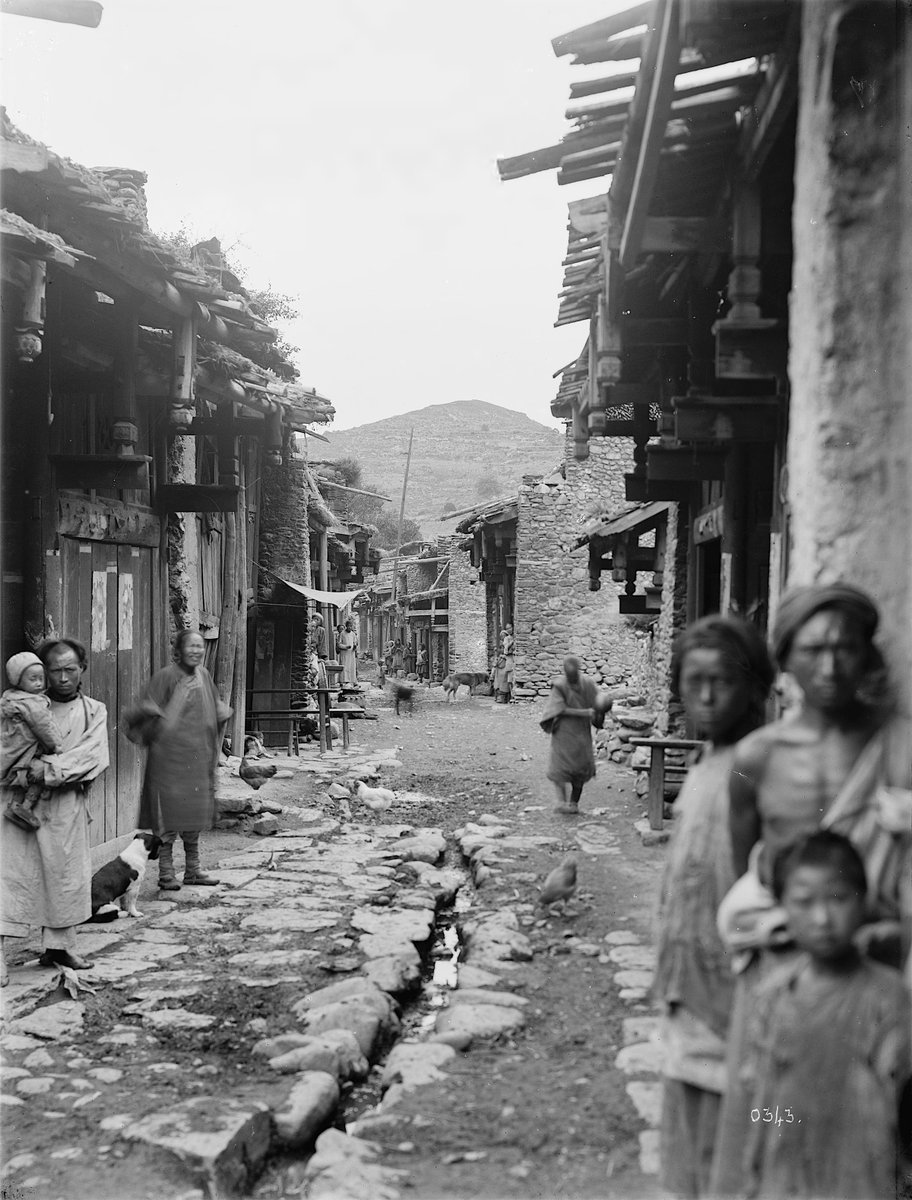

Catherwood & Stephens had to battle malaria and hack their way through heavy undergrowth. Or at least, their porters did: one of the most interesting things about Catherwood’s drawings is the people he included. This is Uxmal, Mexico. [4/6]

One of my favourites, drawn at Labna, Mexico. I tried to photograph the arch from the same spot in 1997… and almost got it right. [5/6]

Stephens & Catherwood had no idea who the Ancient Maya were, or where they had gone; it would be well over a century before the Mayan code was cracked. Their work, however, had got the world’s attention. You can see more here: [6/6] casa-catherwood.com/catherwoodinen…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh