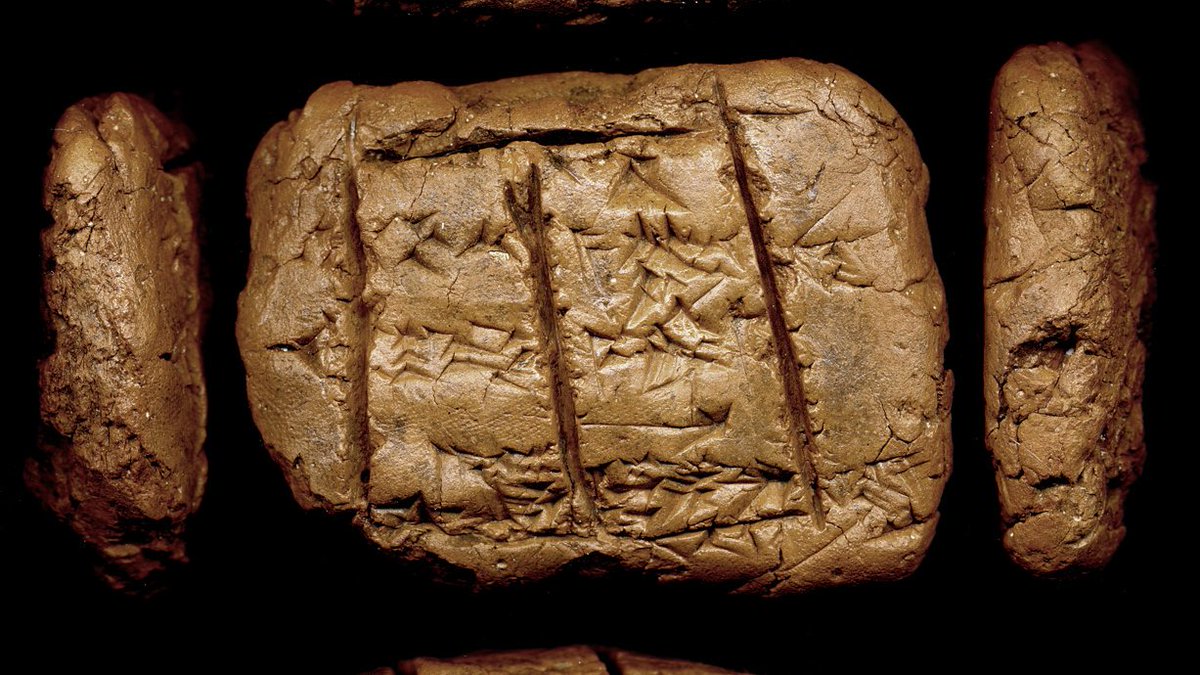

A clay tablet made by a young scribal student who was practicing the "A" sign 𒀀 over and over again at school almost 4,000 years ago in Babylonia.

Be still my heart 🥺

Be still my heart 🥺

A Babylonian scribal student practicing the sign "DINGIR" 𒀭 which looks like a star sometime between 2000 and 1600 BCE

This Babylonian student got bored and drew a doodle on his school exercise tablet ~4,000 years ago in Iraq

This Babylonian student left his now almost 4,000-year-old fingerprints on what looks like maybe a math exercise text from ancient Iraq

Compare this work of a young Babylonian scribal student practicing signs with that of a seasoned student writing out a mock lawsuit in cuneiform 🥺🥺

A Babylonian artist in the making several millennia ago in a scribal school in what is now Iraq.

On one side of a clay tablet, there are writing exercises and on the other side, this lovely drawing of a fish and a goat (I think) 🧡

On one side of a clay tablet, there are writing exercises and on the other side, this lovely drawing of a fish and a goat (I think) 🧡

I love these so much 🧡

All of these Babylonian school tablets are from the UCLA special collections, and you can peruse them here oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/1…

I somehow broke the thread so here’s the rest of it, complete with kids’ fingerprints and drawings

https://twitter.com/moudhy/status/1415621839812968452

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh