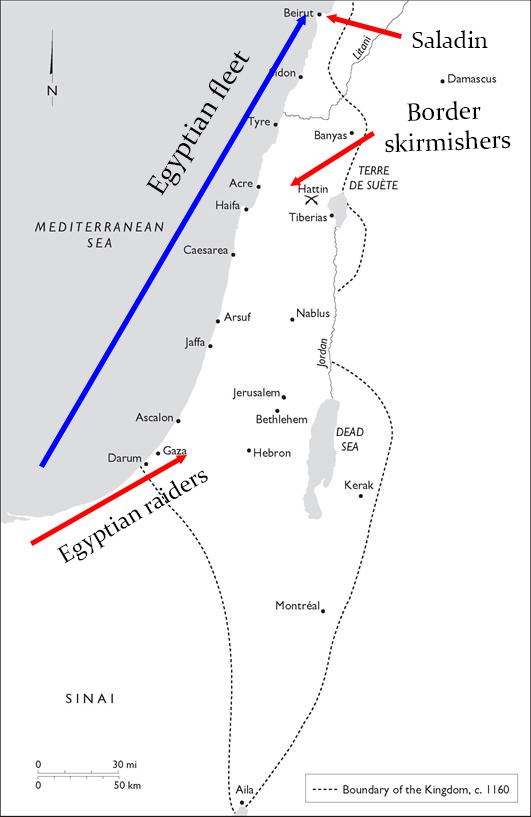

In 1182, Saladin launched a daring attack by land and sea on Beirut.

It was a sharp break from his usual raids into enemy territory and skirmishes with the Crusaders. But at a deeper level, it was part of a consistent strategy that ultimately brought him victory.

Thread

It was a sharp break from his usual raids into enemy territory and skirmishes with the Crusaders. But at a deeper level, it was part of a consistent strategy that ultimately brought him victory.

Thread

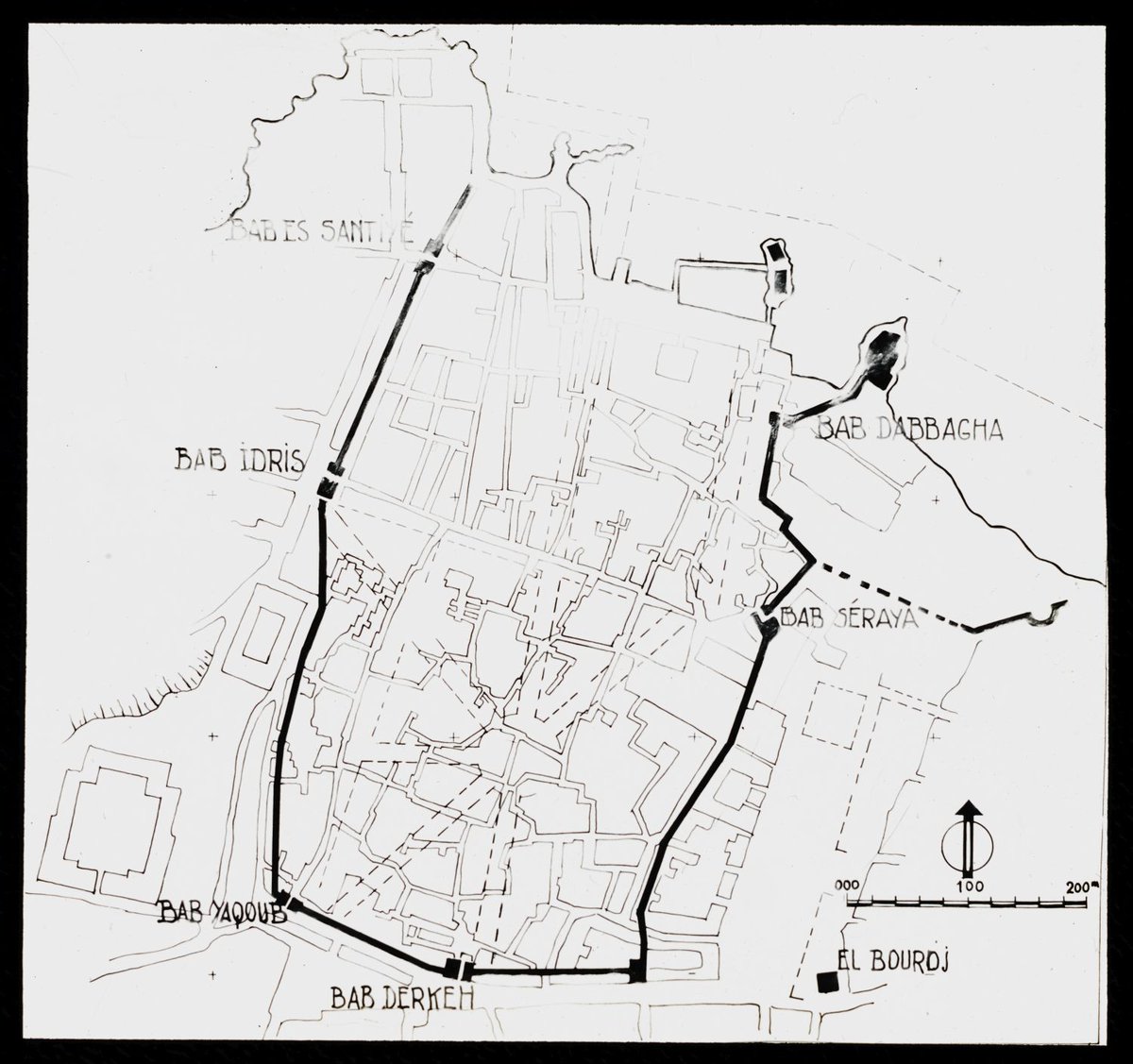

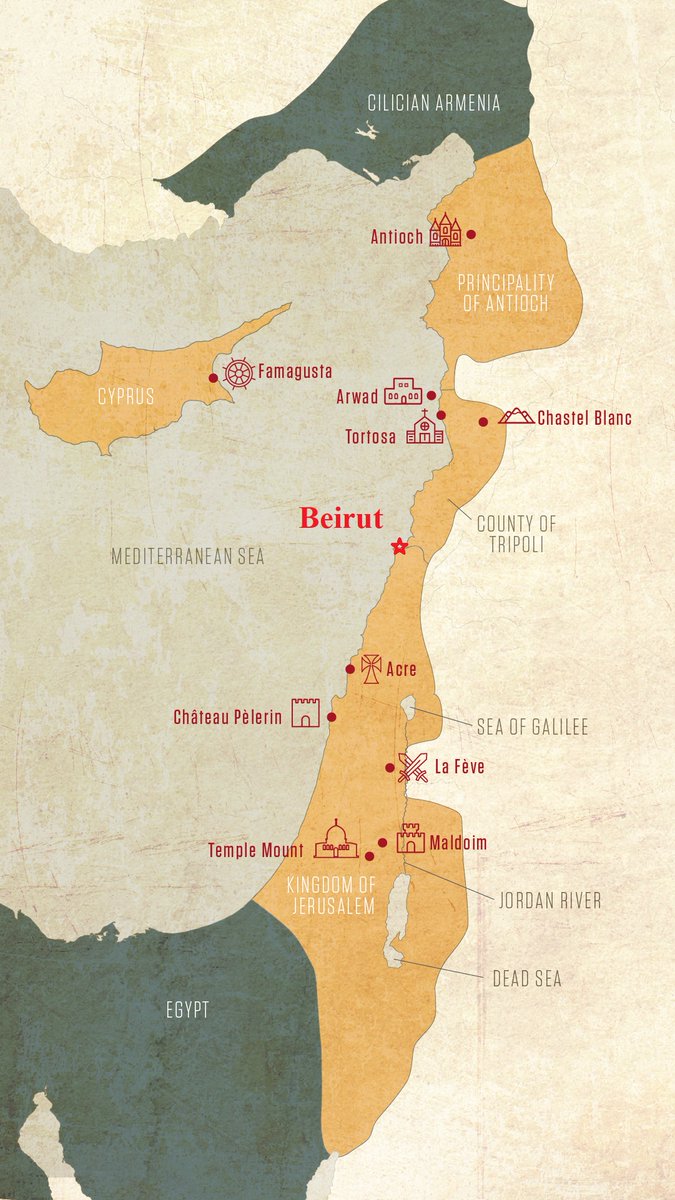

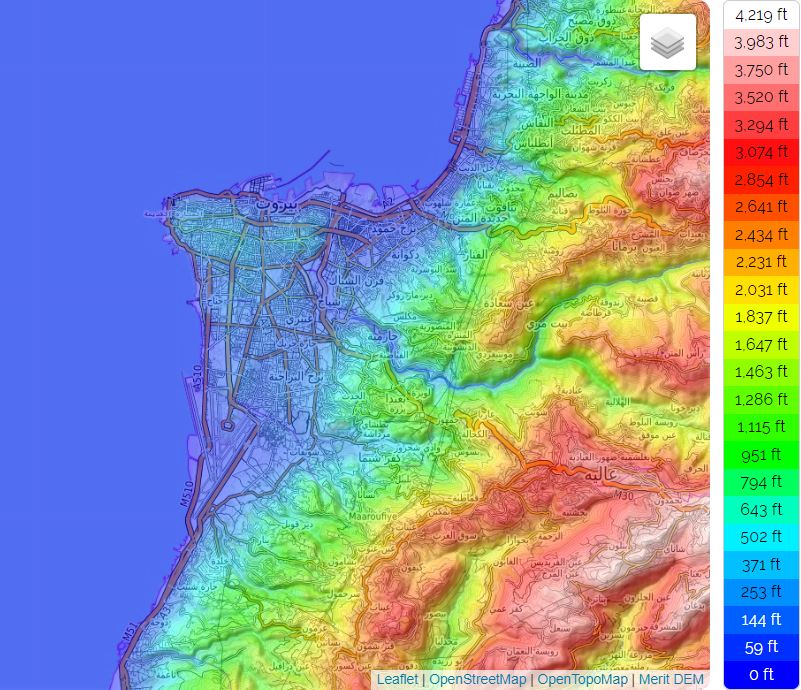

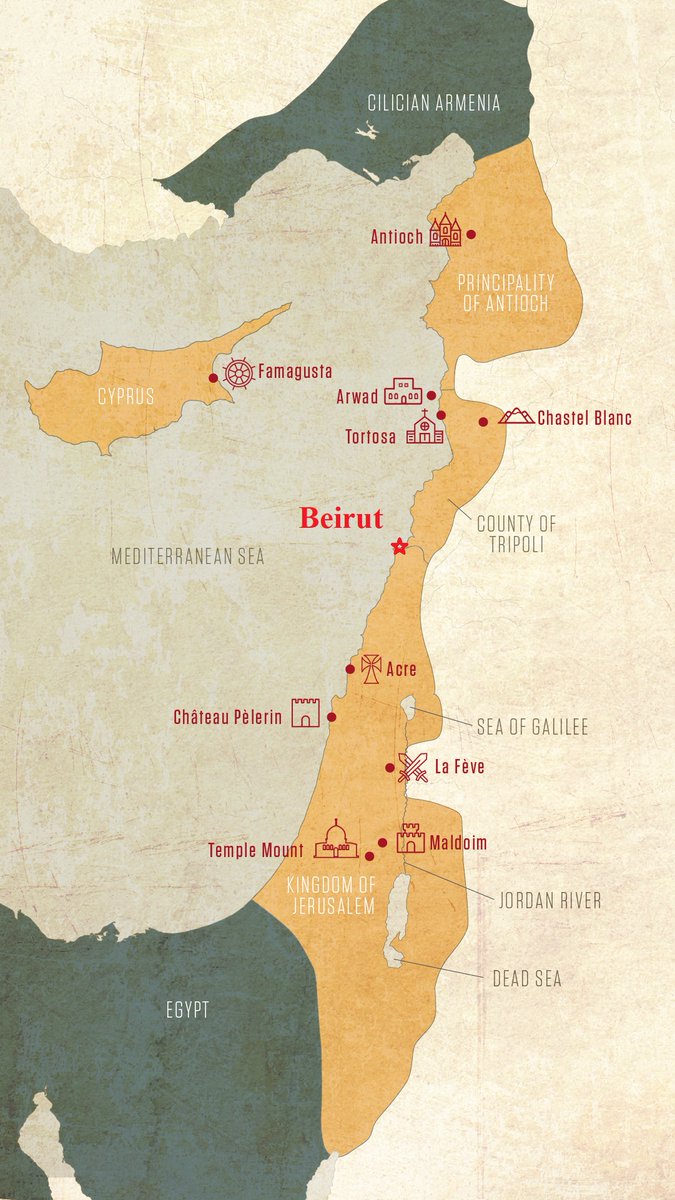

Beirut stands on a broad triangular promontory, which in Saladin’s time was covered with fields and orchards. The medieval city stood on its northern edge and was endowed with one of the finest harbors in the Levant.

Beirut was obviously an attractive target, but this was uncharacteristically bold for Saladin. This was not just a raid: it was an attempt to seize and hold ground in the middle of Crusader territory.

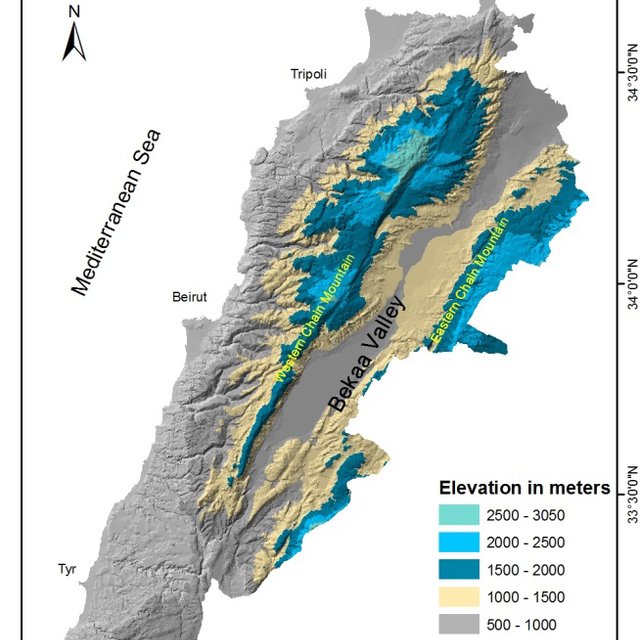

More important in Saladin’s calculations were the surroundings. Mountains come down to the sea on either side, squeezing the coastal road along the shore. Only a few narrow paths crossed the mountains.

From a military point of view, Beirut was virtually an island.

From a military point of view, Beirut was virtually an island.

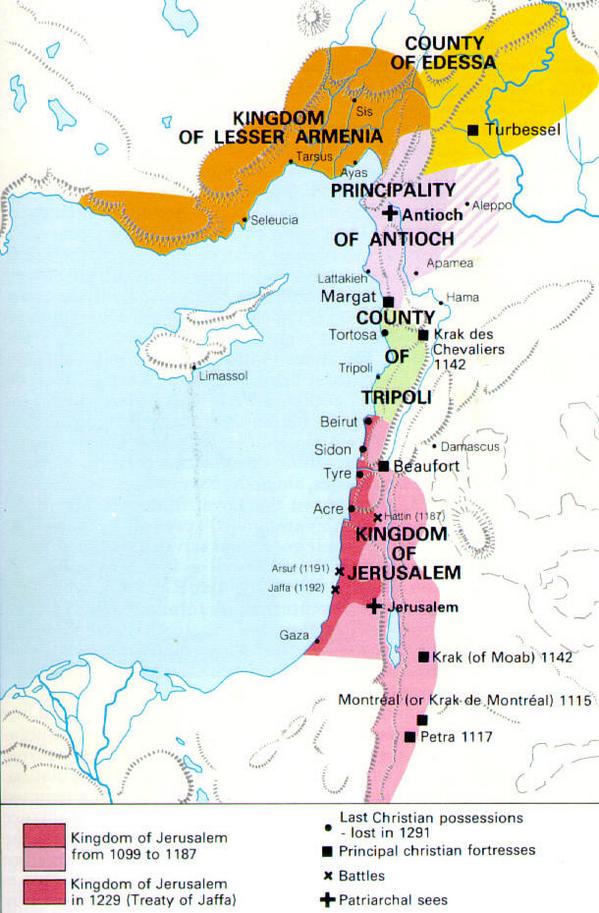

The Crusaders’ only practical land access was by the coastal road: from the County of Tripoli to the north or Kingdom of Jerusalem to the south. Over the mountains lay the Beqaa Valley, which was under Saladin’s control.

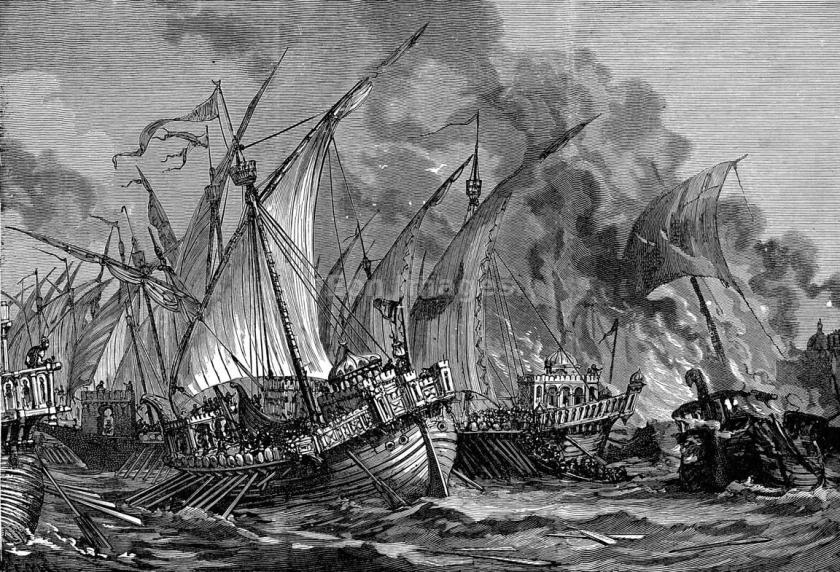

The only other access was by sea. Traditionally the Crusaders had command of the seas, aided by Venetian, Genoese, and Pisan ships. As part of his long-term strategic reforms, Saladin began rebuilding the Egyptian navy in 1176.

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1393286425882288133

This allowed him to launch sea raids every spring with the opening of the Mediterranean sailing season. In their first few forays, the Muslims had some modest successes, capturing a few Christian ships.

In 1182, Saladin decided to undertake something more ambitious.

In 1182, Saladin decided to undertake something more ambitious.

The sultan had spent the winter in Egypt. After arranging affairs there, he departed in spring for Damascus then conducted multiple raids through Galilee. This kept the Crusaders focused on their eastern frontier.

Saladin left a modest force to guard the border, then in July brought most of his troops up to the Beqaa Valley. He posted lookouts in the mountains above to keep watch for a signal….

On August 1st the lookouts spotted the signal: 40 galleys sailing up the coast from Egypt. They sent word to Saladin, who immediately set off across the mountains with the army.

While Saladin was crossing the mountains, a raid force came up from Egypt right on schedule and began devastating the land around Gaza. Skirmishes in Galilee sparked rumors of an attack from that direction, then reports began arriving from the north…

Confusion reigned among the Crusaders. They were assembled and ready to march, but reports were coming in of attacks from all directions. The army was paralyzed, not knowing which was the main attack.

Saladin had meanwhile descended to the plains around Beirut and immediately settled in to invest the city. He hadn't brought his siege engines, which would slow him down, but had his crack sapper corps with him.

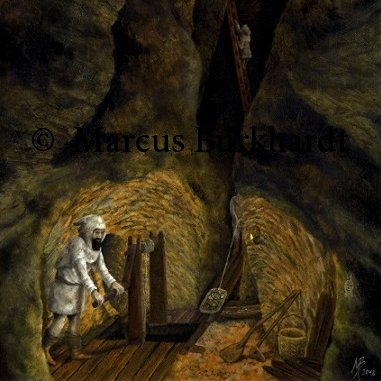

The sappers immediately began entrenching and digging mines beneath the walls, while archers kept up a continuous rain of arrows to keep the defenders’ heads down. The galleys meanwhile kept up pressure on the harbor.

There were only a few soldiers in the city (most of the garrison had joined up with the main army), but the bishop organized the townspeople into a defensive brigade. They worked around the clock and successfully countermined the siege tunnels.

After three days, it was apparent that a successful siege would take a while longer. One of Saladin’s commanders suggested a direct assault on the walls, which were guarded by only a few fighting men—no sooner did he say that than an arrow pierced his throat.

The Crusaders had meanwhile realized the gravity of the situation at Beirut. King Baldwin marched with his army to the great port city of Tyre and ordered the fleet made ready.

Saladin, in the meantime, sent his infantry to build a wall blocking the coastal route from the south and devastated the plain around Beirut with his cavalry. He ordered his ships, which could not compete with the superior Christian navy, to return home.

After a few days, he achieved all he could hope to and saw no more opportunities to take the city. He gathered all his forces and withdrew over the mountains.

The siege of Beirut was a failure, but one that cost Saladin nothing—in fact, he gained plunder and damaged the Crusaders. Success, on the other hand would have brought him a great deal….

Seizing Beirut would have split the Crusader states in two, preventing Tripoli and Antioch from reinforcing Jerusalem and vice-versa. It also would have given his fleet safe harbor to continuously raid the coast.

Although Saladin never tried anything quite so bold before or after, it was characteristic of his larger strategy: make continuous small-scale attacks on the Crusaders while probing for vulnerable points, exploiting opportunities as they came.

This depended on careful preparation, good intelligence, and above all disciplined execution. It had a narrow window of success which had to be ruthlessly exploited, unlike longer, large-scale sieges.

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1411017267358355457

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh