Where are India’s biologically-significant Open Natural Ecosystems (ONEs)?

Thread 👇🏽 on a new, open, and analysis-ready dataset on the distribution of India’s beautiful and beleaguered semi-arid Open Natural Ecosystems. (Representative image for each of the ecosystem types).

Thread 👇🏽 on a new, open, and analysis-ready dataset on the distribution of India’s beautiful and beleaguered semi-arid Open Natural Ecosystems. (Representative image for each of the ecosystem types).

A large fraction of India’s landmass is semi-arid (annual rainfall < 1000 mm). The native vegetation in this zone is made up of grass, herbs and shrubs. They are often naturally without trees, and if at all trees do occur, cover is sparse. Yet, ONEs are staggeringly diverse.

Mirroring the diversity of habitats, ONEs also have a remarkable diversity of animal species, many of which are unique to the Indian subcontinent.

ONEs also are our primary rangeland habitats, which sustain grazing-based livelihoods of millions from of pastoral and agro-pastoral communities across the country.

These communities, with their diverse and rich pastoral and agro-pastoral cultures, have also had a long history of coexistence with these ecosystems, and their unique wildlife.

Besides being home to unique life-forms, and providing sustenance to local communities for millennia, they provide valuable ecological services. Research shows that, under certain environmental conditions, ONEs can sequester *more* carbon, than if trees were planted on them!

Yet, India’s ONEs continue to be misunderstood, misrepresented, and destroyed routinely. Successive governments have officially termed them 'wastelands', and led the charge against them, seeking to make them ‘productive’ and to ‘develop’ them, thereby incentivising their erasure.

Such ill-informed efforts to ‘develop’ ONEs result in a range of ecological incursions, such as the road cutting across this grassland here. But, in recent times, the two most significant threats to ONEs come from, wait for it, renewable energy and tree-planting projects.

Renewable energy technologies—wind and solar power, in particular—have become pivotal in a low-carbon energy economy. But, both wind and solar power are heavily reliant on the availability of open spaces. What better places to target for such ‘development’ than our ‘wastelands’?!

But here is the catch: to generate hundreds of gigawatts of power at the grid-scale, we end up with a geographical & ecological footprint of energy production—even with wind and solar technologies—that are environmentally and socially just as huge as that of a large hydel dam.

This (entirely avoidable) overlap of renewable energy projects and critically endangered fauna like the Great Indian Bustard has led to serious contestations going all the way to the Supreme Court. More on that here:

https://twitter.com/mdmadhusudan/status/1405086002775924739

But the scales are already tilted heavily against ONEs. Our remaining ONEs are rapidly being lost to colossal renewable energy projects that may be well-meaning but are ill-conceived and poorly-implemented.

Likewise, in recent years, there has been a spurt in ill-conceived plans of tree-planting—even where they were never meant to be—as a way of capturing atmospheric carbon into biomass. As a result, wildlife habitats in ONEs are being destroyed as they get planted over with trees.

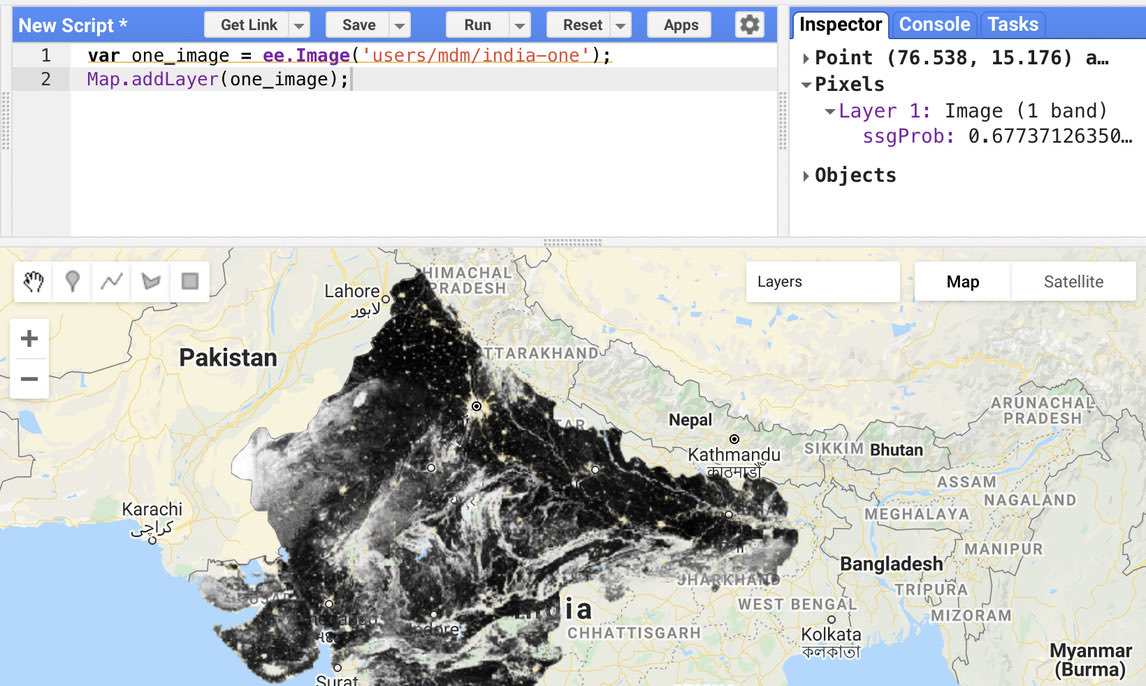

A key knowledge gap that has constrained us from more effectively protecting our valuable open natural ecosystems is the absence of a reliable map of the distribution and extent of our Open Natural Ecosystems. This, specifically, is the gap that our dataset hopes to bridge.

To make the visualisation and inspection of our data at state/district levels easy, particularly for journalists and policy-makers, we built an interactive app, which is available at http://tiny.url/open-natural-ecosystems.

For researchers, our data are available as an analysis-ready image within the Google #EarthEngine platform. From here, specific areas of interest can be exported and downloaded, or the layer called in QGIS via the GEE plugin.

More detail about our motivations and methods is available in this preprint: Mapping the distribution and extent of India’s semi-arid open natural ecosystems essoar.org/doi/10.1002/es…

We—@atree_org & @abi_vanak—see this map as the first step in a long road to making our ONEs first-class ecological citizens, worthy of care and conservation. This is work in progress, to be iterated and improved upon. So please do share your comments, corrections, or suggestions.

This video unfortunately didn’t seem to load in the threaded tweet…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh