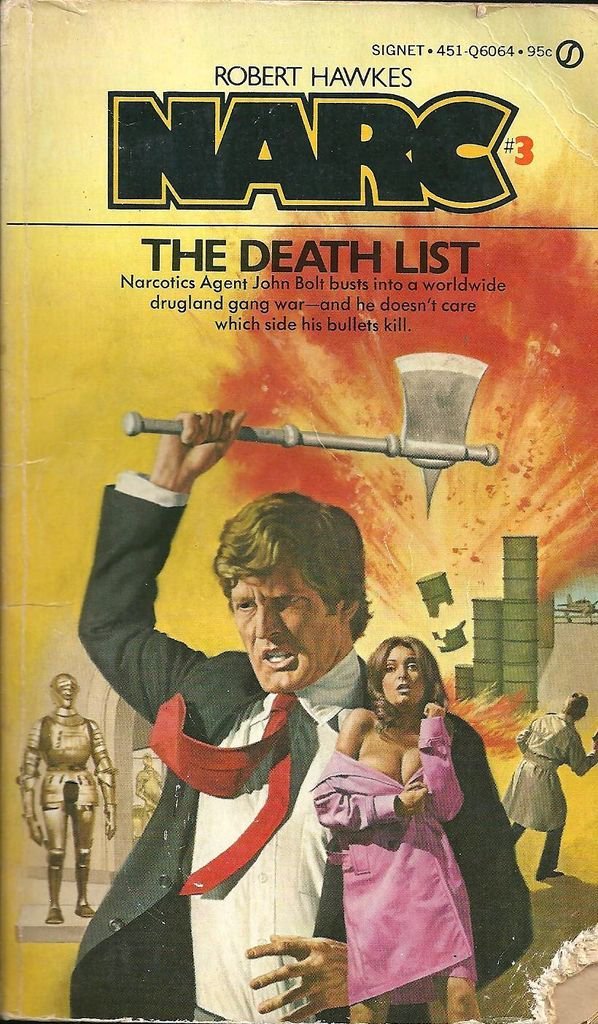

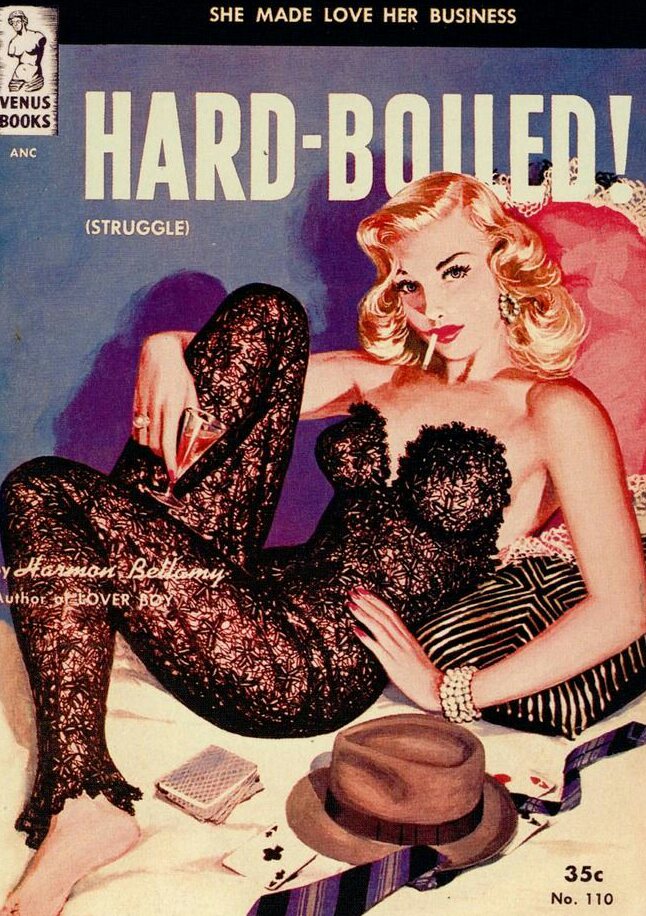

JX Williams was an alias used by many writers who knocked out cheesy sex pulp for Greenleaf publishing. At least 20% of each novel had to be sex scenes with the other 80% titillation, voyeurism or padding.

As a result Greenleaf plots were somewhat thin affairs: sexy sensationalism was more important than character arcs or the niceties of the three act drama.

William Lawrence Hamling set up Greenleaf publishing in 1950, initially specializing in science fiction magazines. By 1959 the company had moved into paperbacks.

By the early 1960s sex was selling better than sci-fi and a number of writers were quietly supplying novels for both scenes. Robert Silverberg Harlan Ellison and Donald E Westlake all provides pseudonymous sex novels for Greenleaf.

And no form of desire was off limits for Greenleaf. What mattered was what sold. Ed Wood Jr was able to pen Parisian Passions for the imprint, though it was never a best seller.

Pulp sex publishers in the early 1960s were, in their own way, blazing a trail for the permissive society. Any sex was good sex and if it felt good then do it!.

It couldn't last...

It couldn't last...

The US Government prosecuted Greenleaf on many occasions under the obscenity laws of the time.

For a while Hamling's luck held...

For a while Hamling's luck held...

But in 1971 Hamling was imprisoned for publishing - of all things - a fully illustrated version of the Presidential Report of the Commission on Obscenity and Pornography.

No prizes for guessing what the illustrations were like...

No prizes for guessing what the illustrations were like...

Appeals against the sentence went in for many years, but Uncle Sam wasn't going to let up. It all ended in 1976 with Hamling on parole but banned from working in the obscene book trade.

By the mid 1970s the obscenity laws had changed, hard core magazines were on the news-stands and cheesy sex novels were on the way out. Turns out the permissive society wasn't that interested in reading.

But let's give a cheer for Greenleaf and the mysterious JX Williams. They fought the law and the law won: but what a fight they put up!

More torrid takes of publishing another time...

More torrid takes of publishing another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh