We are heavily influenced by the behaviour and attitudes of others. The effect is particularly powerful when a large proportion of a group act in a similar way.

→ These unwritten rules of conduct are known as 'norms' and they play a HUGE role in school.

🧵...

→ These unwritten rules of conduct are known as 'norms' and they play a HUGE role in school.

🧵...

First, let's take a step back. Why do norms exist?

Firstly, an ‘imitation’ shortcut to behaviour makes sense from a risk point of view—if those around us are doing it, it can’t be all that bad a bet, right?

Firstly, an ‘imitation’ shortcut to behaviour makes sense from a risk point of view—if those around us are doing it, it can’t be all that bad a bet, right?

Secondly, conformity is a critical pre-condition for large group co-operation. Working together at scale can supercharge our individual and collective success.

But these things are only possible when the behaviour of individuals within a community is consistent and predictable.

But these things are only possible when the behaviour of individuals within a community is consistent and predictable.

As a result, we have evolved a tendency not only to imitate norms, but also to enforce them. Where norms are established, individuals within a group often work together to penalise those who don’t conform.

Going with the norm is both a quick and safe bet.

Going with the norm is both a quick and safe bet.

Norms are so powerful they often override more formal school policies or rules.

However, their largely invisible and unconscious nature makes them easy to underestimate, if not totally ignore.

However, their largely invisible and unconscious nature makes them easy to underestimate, if not totally ignore.

The *presence* of norms in school is inevitable—there is little we can do about it. However, the *nature* of these norms is within our influence.

Norms can be a powerful lever for improving student behaviour, learning and wellbeing.

Norms can be a powerful lever for improving student behaviour, learning and wellbeing.

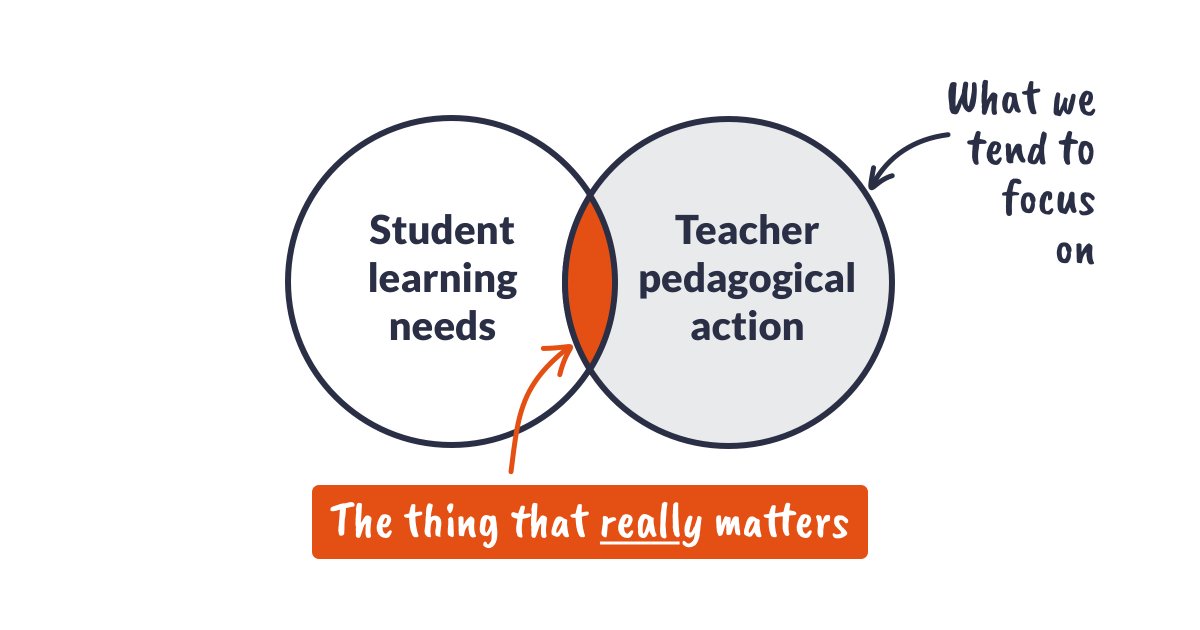

The norms students hold arise predominantly from their observation of others. We can make desirable norms more visible by increasing:

→ The proportion of students that appear to conform to a norm

→ How visceral and memorable our sightings of norm compliance are

→ The proportion of students that appear to conform to a norm

→ How visceral and memorable our sightings of norm compliance are

100% adoption is the ultimate lever—even a single dissenter makes it easier for us not to follow along.

When we see one person picking up litter, doing it ourselves becomes a slightly safer option. When we see everyone picking up litter, not doing it ourselves becomes a risk.

When we see one person picking up litter, doing it ourselves becomes a slightly safer option. When we see everyone picking up litter, not doing it ourselves becomes a risk.

Where there isn’t an established norm, we can point to evidence of an emerging norm, one that appears to be growing in adoption or approval.

Or we can point to norm outcomes. A full pile of homework books handed in or a tidy classroom signal 'how things are done around here'.

Or we can point to norm outcomes. A full pile of homework books handed in or a tidy classroom signal 'how things are done around here'.

Our perception of norms is not just influenced by the actions of others, but also their attitudes.

Approval can be signalled by teachers: what we permit, we promote. But it is much more powerful when it comes from peers.

Approval can be signalled by teachers: what we permit, we promote. But it is much more powerful when it comes from peers.

Peer approval is why regular exposure to positive role models can be so powerful.

When we see someone we identify with achieving, or simply acting like they believe they can, this opens up our own possibility space.

When we see someone we identify with achieving, or simply acting like they believe they can, this opens up our own possibility space.

Normative messaging is most potent in novel situations. This is why it is worth taking time to get things right in the early days of establishing a class.

Once norms have taken hold, they become increasingly hard to change.

Once norms have taken hold, they become increasingly hard to change.

This is why some schools host new classes for a few days at the start of the year, before the rest of the school begins.

It provides the elbowroom needed to get desirable norms and routines established before the rest of the party arrive.

It provides the elbowroom needed to get desirable norms and routines established before the rest of the party arrive.

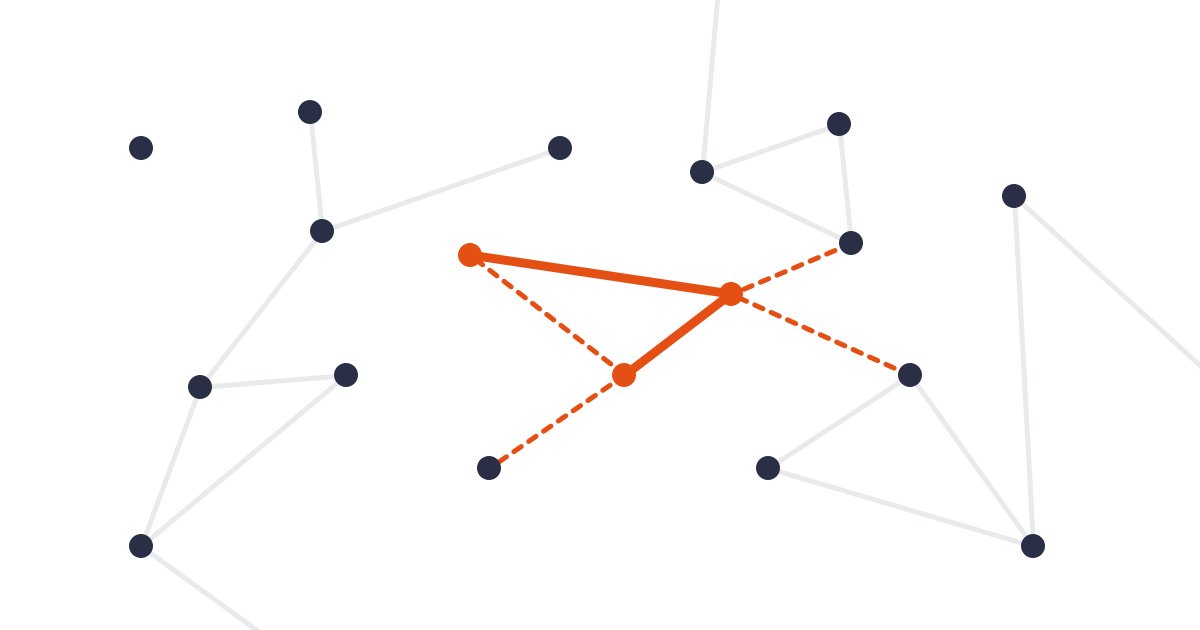

Finally, the norms of different groups within a school will naturally bleed into each other. When these norms oppose each other, both attenuate. But when support each other, both grow stronger.

Another reason why teacher consistency is such a desirable feature of school.

Another reason why teacher consistency is such a desirable feature of school.

Nuance: normative messaging appears to be more effective when it emphasises what we want to happen, rather than what we don’t.

Chastising a class by messaging that the majority of them didn’t do their homework is more likely to act as a reinforcement rather than a deterrent 🤦

Chastising a class by messaging that the majority of them didn’t do their homework is more likely to act as a reinforcement rather than a deterrent 🤦

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh