Happy #808day everybody! And as we're celebrating the Roland TR-808 Rhythm Composer I make no apologies for sampling one of my favourite previous threads.

This is the story of digital synthesised music...

This is the story of digital synthesised music...

In the 1940s Musique Concrète introduced the idea of sampling and sound distortion into musical composition - often with the help of audio tape splicing.

It was all very avant-garde, but it was limited by the available technology.

It was all very avant-garde, but it was limited by the available technology.

However by 1957 the massive experimental RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer had shown composers how an analogue synthesizer could be paired with a programmable sequencer to play music too complex for human musicians to manage.

Yes, it is big.

Yes, it is big.

The Moog synthesizer debuted in 1964. With separate oscillators, envelope generators, modulators, amplifiers and other ways to create and shape electronic noise it was the first commercial analogue synthesizer. Composer Wendy Carlos was an early pioneer of its unique sound.

Analogue drum machines also began to emerge in the 1960s, each with a distinctive sound. Ikutaro Kakehashi was hugely influential in their development, working at Ace Tone in the 1960s (pioneers of the Rhythm Ace drum machine) before founding Roland in 1972.

Just as important as the synth was the sequencer: hardware or software to record and play back sequences of notes. Step sequencers were common in drum machines, letting you programme complex percussion. Others could be connected to analogue synths to allow complex arrangements.

By the early 1970s portable analogue synths and sequencers meant any band worth it's salt had to have an analogue knob twiddler staring at an oscilloscope. Sonic swoops and kling-klang beats were in, and the keyboard player was the new magician of pop.

Some musicians went even further. Kraftwerk designed their own drum synthesizer and sequencer, though their light controlled drum kit was less successful. It looked like music and machines were becoming a perfect match.

However...

However...

Early analogue synths could be tricky things. Normally monophonic they took some setting up, and didn't always stay in tune for long. Long delays because someone plugged in the wrong patch chord or stood on the step sequencer made some musicians curse these electronic newcomers.

But over time improvements did happen: patch chords gave way to integrated units and polyphonic synths became more common. The Sequential Circuits Prophet 5, launched in 1978, was one of the most popular (and reliable) of the later analogue synths.

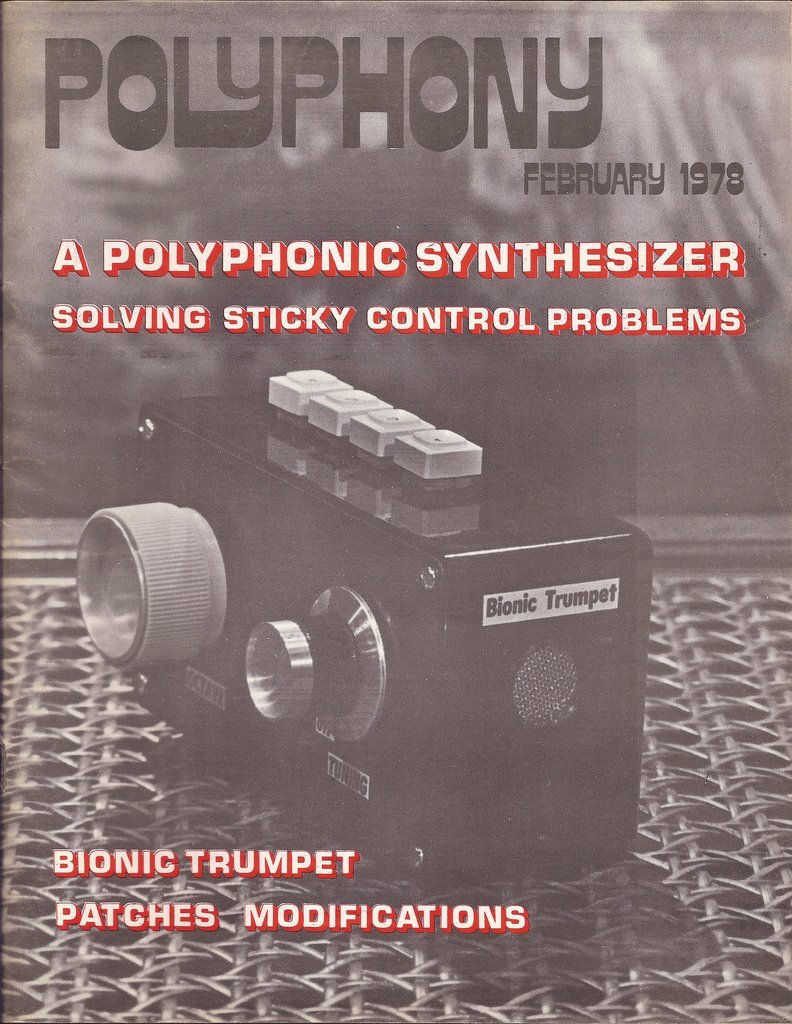

But it was a pain to sequence instruments from different manufacturers because there was no shared technical standards. Plus prices were still high. Despite the interesting music the analogue synth was not quite ready to lead the band - Bionic Trumpet notwithstanding!

Fortunately there was a new kid on the block: digital synthesis! In 1973 Yamaha licenced the algorithms for frequency modulation synthesis, which they then used to built a prototype digital synthesizer in 1974.

The New England Digital Synclavier, launched in 1977 and updated in 1980, was one of the first digital synths to use FM synthesis. Later models allowed digital sampling to magnetic disc, meaning that a vast range of new sounds were available to you. It was also polyphonic.

The 1979 Fairlight CMI took things a stage further with digital sampling, three sequencers and 28Mb of memory built in. It cost the same as the average house, but that didn't stop Peter Gabriel from buying the first one.

At the other end of the price spectrum was the 1979 Casio VL-Tone - a combined calculator, synthesizer and sequencer the size of a half baguette. It may have looked like a toy, but it introduced a generation to programmable music.

Drum machines were also going digital. The 1982 LynnDrum was one of the first to digitally sample, sequence and play real drum sounds, while the Roland TR-909 offered a hybrid mix of analogue synthesized sounds and digital samples.

More importantly in 1982 the MIDI technical standard was agreed. A MIDI link could carry up to sixteen channels of data, allowing synths, sequencers, drum machines and anything else MIDI-enabled to work together. Studio-level technology was suddenly available to anyone.

And then... in 1983 Yamaha launched the mighty mid-priced DX7; polyphonic, programmable and MIDI-enabled. It may be the best selling digital synth of all time. It certainly became one of the dominant sounds of '80s synthpop.

The digital synthesizer began to influence more and more musicians, especially as it could be linked to more than just keyboards. Guitar synths, wind synths, virtual synths - you name it and FM synthesis was probably trying to be compatible with it.

And thanks to the keytar - particularly the Roland SH-101 - the keyboard player was no longer stuck at the back with the drummer. Now they could dance at the front of the Top Of The Pops stage with the guitarist!

The MIDI standard made it much simpler (and cheaper) to link synths to computers. With a MIDI sound card - plus a music macro language programme - a single person could programme a complete song through various synths without needing to read or understand music notation.

The Atari ST, launched in 1985, certainly owed some of its success to having built-in MIDI ports, along with a reasonable price tag. From Tangerine Dream to Fatboy Slim the ST has powered a number of artists. Atari Teenage Riot even named themselves after it.

Analogue didn't die away however, instead it helped drive forward a lot of new underground music. The Roland TR-808 analogue drum machine became a powerhouse of 80s and 90s dance music.

Similarly the Roland TB-303 analogue bass synth may have been a flop when it was released in 1981, but second hand models created the sound of Acid House in the late 1980s. Analogue and digital weren't rivals, they were friendly competitors.

Today modern computers can emulate almost any type of synth or rhythm machine - analogue or digital. The synth is certainly here to stay, and music is (probably) all the better for it.

More future sounds another day...

More future sounds another day...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh