(1/8) Our study on questionable research practices (QRPs) and open science practices (OSPs) is now published in JQC. Data are public, link below is to open access version. This thread summarizes the findings. @socpsychupdate @ceptional @siminevazire

rdcu.be/cvwK5

rdcu.be/cvwK5

(2/8) First, we review the evidence on the prevalence of QRPs and OSPs in other disciplines, besides criminology. Unfortunately, QRPs are common in all disciplines where scholars have looked.

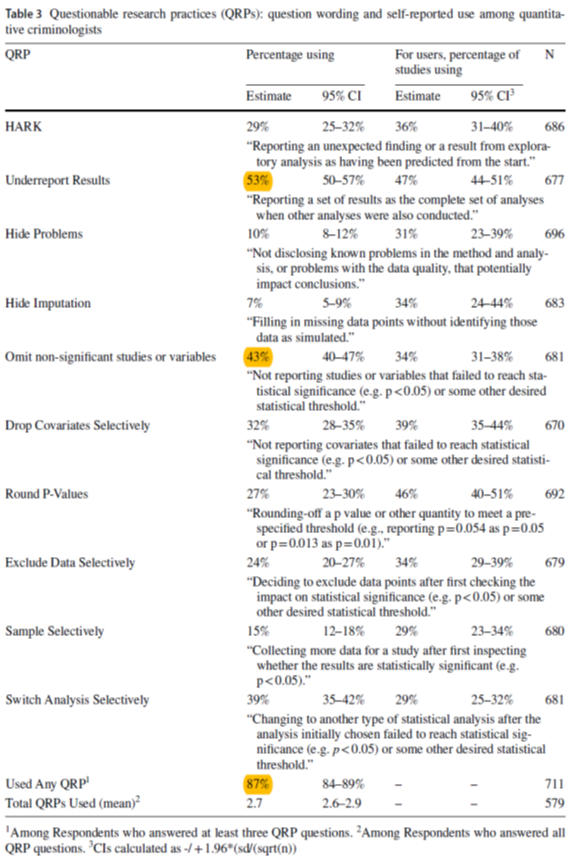

(3/8) We find that the vast majority of criminologists have used QRPs. The average criminologist has used multiple QRPs. One of the most common QRPs is selectively reporting significant studies/findings. Hence, publication bias is a real threat to evidence-based crime policies.

(4/8) OSPs are common in criminology, about as common as in other disciplines. The most common OSP is posting an article publicly, which is also similar to other disciplines. OSP users are also more likely to use QRPs, which is weird (we discuss some possible reasons why).

(5/8) Criminologists perceive a high prevalence of QRPs in their discipline, but the uniform distributions for many of the perceptual questions suggest that criminologists really don't know what their peers are doing in terms of research ethics (= weak descriptive norms).

(6/8) In terms of support, there is a non-trivial percentage of criminologists who believe it is sometimes ok to do things like file drawer null results (67%) or fill in missing values WITHOUT informing readers (18%).😟The latter is arguably data fraud.

(7/8) Support for open science is even higher. The vast majority of criminologists support each OSP. That is good news! The implication is that there is likely to be little resistance to changing journal policies. So, why don't we do it?

(8/8) Methods training appears to have little association with use of QRPs or OSPs. It also appears to have little association with views about QRPs or OSPs. The implication is that QRP use may not reflect ignorance; QRP users may be fully aware of what they are doing.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh