Traditional pattern camoflague had been used by the British Royal Navy to break up a ship's outline for some time. But in 1917 artist Norman Wilkinson presented the Admiralty with a different idea - camoflague that confused the enemy rangefinders.

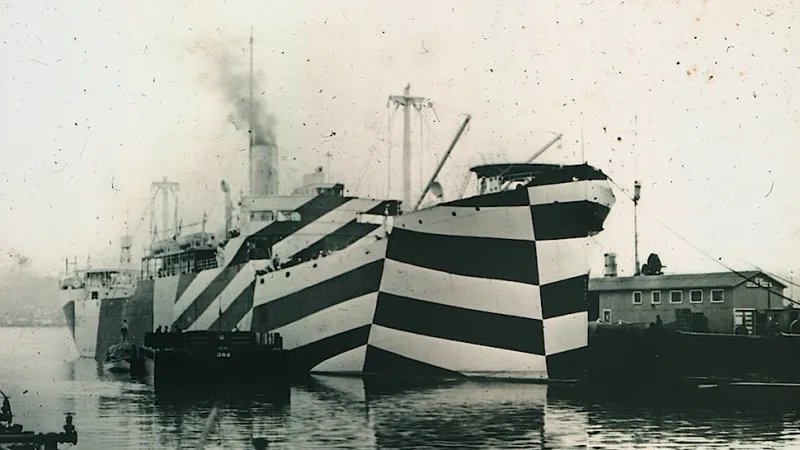

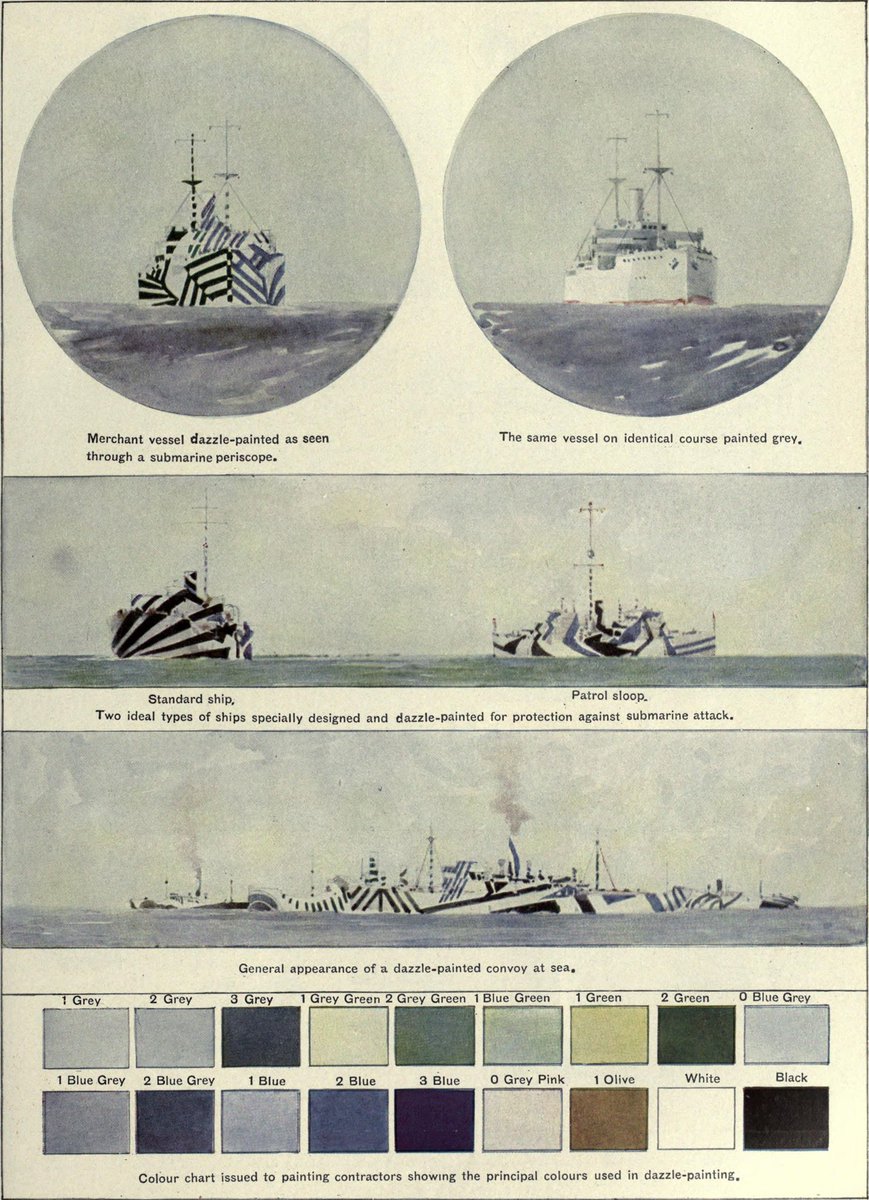

Dazzle - known in the US as Razzle Dazzle - would use high contrast colours in irregular patterns to make it difficult for enemy gunners to calculate a ship's range and bearing. This would (hopefully) lead to them taking up a poor firing position when they attacked.

When seen through a periscope, or a coincidence rangefinder, a ship's irregular appearance due to dazzle camoflague would make it much harder to hit. Were you looking at its bow or stern? Was it turning? Accelerating? Confision rather than concealment was the aim.

The Admiralty agreed, and over 4,000 ships adopted dazzle camoflague during WW1. There were no standard patterns or colour schemes used - each ship would be unique in its paint scheme.

Dazzle was based more on artist intuition than on scientific knowledge: patterns were painted on wooden models by Royal Academy of Arts students, then viewed with a periscope. If they seemed to work they were adopted.

There was also some disagreement over who had invented dazzle. Zoologist John Graham Kerr had pitched the idea of disruptive camoflague to the Navy in 1914. However this was for concealment. Dazzle was for confusion, and by 1922 the Navy decreed Wilkinson had invented it.

Some attempts were also made to use dazzle camoflague for WWl snipers. How well this would work is a moot point.

Dazzle captured the imagination of artists - Pablo Picasso one claimed to be its progenitor. Dazzle paintings and even dazzle swimsuits were created as a result.

Did it work? Later analysis proved inconclusive: there were too many variables to consider. It sounded logical though, and many navies adopted dazzle camoflague during WWI.

By WWII radar had made dazzle less effective in deceiving the enemy, and ships went back to a mix of gradiated grays and blues to blend into the background. However some torpedo boats still used dazzle in WWII.

And Dazzle is still used today on high-end test cars to make them harder to photograph. Sometimes the best way to avoid the limelight is to give 'em the old Razzle Dazzle!

More tech another time...

More tech another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh