Hello class. I'm @tdgraff and will be your guest lecturer in the BBB series today on Mortgage Backed Securities. For background, I'm a buy-side PM today but I actually came up as an MBS analyst, and one of the strategies I run is mortgage specific.

https://twitter.com/EffMktHype/status/1406669892611305474

I'll try to live up to @EffMktHype's standards, but no promises :)

We'll cover what MBS are, how they trade, how you analyze them, who the buyer base is, what a CMO is, when MBS tend to outperform, and whatever else the audience asked about.

We'll cover what MBS are, how they trade, how you analyze them, who the buyer base is, what a CMO is, when MBS tend to outperform, and whatever else the audience asked about.

@EffMktHype I'm going to focus on "agency" MBS, which are the ones backed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac or Ginnie Mae. Non-agency MBS (like what blew up in '08) are a far smaller portion of the market, and TBH should be covered in a discussion of ABS/CMBS, which I'm not going to get into here.

@EffMktHype First, the MBS market is huge, at about $11.5 trillion according to @SIFMA. That's about $1 trillion bigger than U.S. corporates, and only topped by Treasuries.

It is also probably the second most liquid market in the world, after U.S. Treasuries. Again according to SIFA, about $300 billion of MBS trade per day, vs. just $40 billion of corporates, $9 billion of munis. Again, only topped by Treasuries (~$620 billion).

Mortgages that are sold to investors are bundled into "pools." The pool might hold as few as a dozen loans or it might hold 100,000+. The bank that originates the loan will sell the loan to one of the GSEs, and will pay a "guarantee fee" before selling it to the public.

Once that happens some bank will become the "servicer." This could be the originating bank or someone else. The servicer is who actually deals with the borrower from here on. I.e., that's who you make your check out to, who would deal with you in delinquency, etc.

Basic MBS are often called "pass throughs." This is because the cash flow "passes through" from the actual borrower to investors. When you send in your monthly mortgage payment some of that is principal and some is interest, which we'll call "P&I" from here on.

The servicer takes a fee out of the interest, then the rest of the interest plus the principal "passes through" to investors. Whatever principal is paid actually reduces the amount of bonds you own. The percentage that is remaining is called the "factor" on a mortgage.

Quick aside: the factor bit makes MBS trading easier. When we transact, the quantity quoted is in "original face" which is how much was originally outstanding. Then the factor is applied.

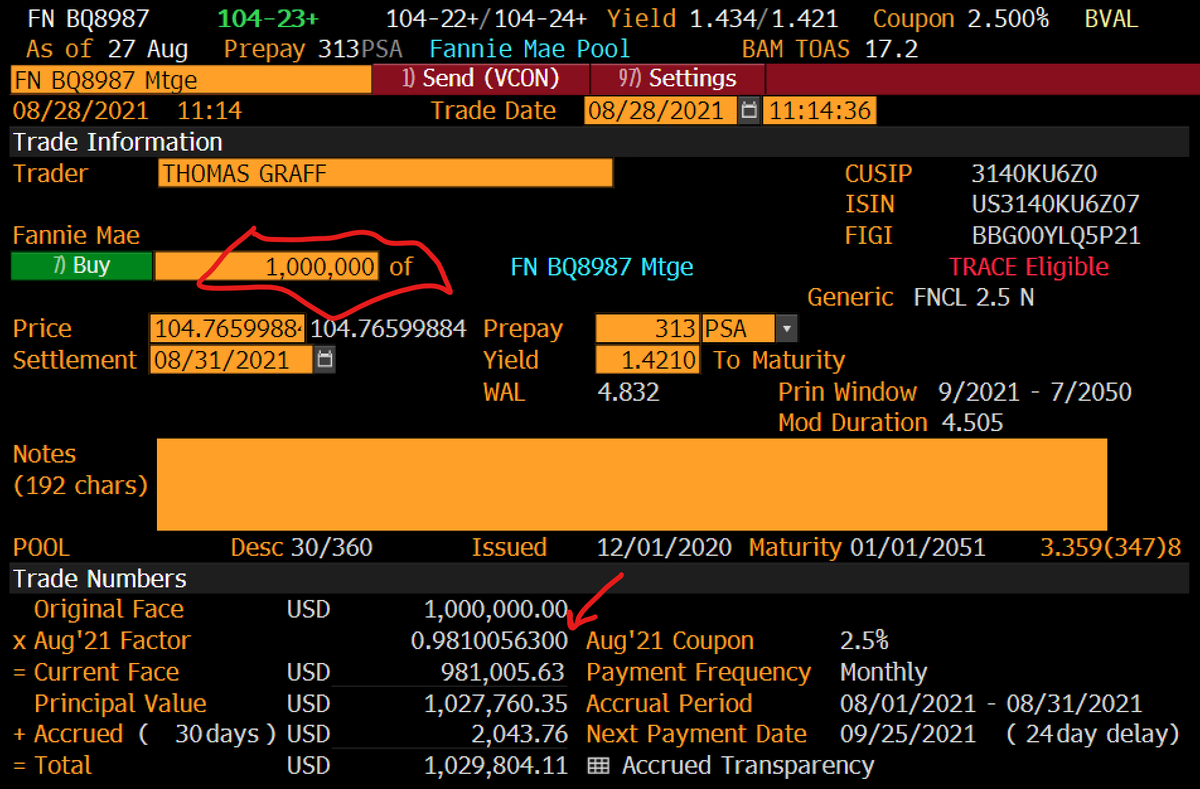

Below is an example using the "BXT" function in BB.

Below is an example using the "BXT" function in BB.

In this example, I'd tell my counterparty that I'm buying 1mm of FN BQ8987 (which is the pool ID) at a price of $104.766. Since this has 98.100563% outstanding, I actually wind up with $981,005.63 "current face."

The GSE's role in all this is strictly as guarantor. If a loan goes delinquent, at first the GSE advances both P&I to investors. However if a loan goes more delinquent for 4 months, the GSE "buys" the loan from the pool at 100% of its original face.

So in essence, any defaults act just like principal repayments from the investors' perspective. Worth noting that long-term delinquencies are rare. According to Fannie, about 1.7% of loans from 2009-2021 are seriously delinquent.

You can see the credit stats for a given pool using the CLP page in BB. This pool currently has zero delinquencies:

Thread continues here with how TBA works:

https://twitter.com/tdgraff/status/1431640600172847107?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh