(1/12) “We were summoned to the house of my girlfriend to discuss the situation. The atmosphere was very tense. Her family on one side of the living room. Mine on the other. Her grandfather was the first to speak: ‘You should be ashamed,’ he told me. ‘For what you’ve done..."

(2/12) “My daughter was born three weeks early. I wasn’t there for the birth; I was working in another town. And that still hurts me today. When I arrived at the hospital I was almost too scared to hold her. She looked so fragile. And all I could think was..."

(3/12) “I sold all my possessions. I even let go of my apartment. But still it was not enough for a camera. So I turned to my mother for help. She sold second-hand clothes for a living. She knew nothing about photography. But when I told her a camera would help me be a father..."

(4/12) “The online tutorials made photojournalism sound easy: ‘Quit your job, find the best story, get published.’ But this advice was for Westerners. Nobody quits their job in Ghana. And even if you did— there’s no place to publish your photos. I’d see pictures from Africa,.."

(5/12) “I’d been rejected at the gate because I didn’t have a ‘body of work,’ so after that day those words became very important to me. I spent all my time in the internet café, researching stories that belonged in a ‘body of work.’ I discovered a blog post about a community..."

(6/12) "It was time for me to face the truth: there wasn’t a path for this kind of thing in Ghana. Photojournalism was not a way to feed my daughter. I stopped looking for stories to tell. I went back to weddings and events, and took any job I was offered. Later that year..."

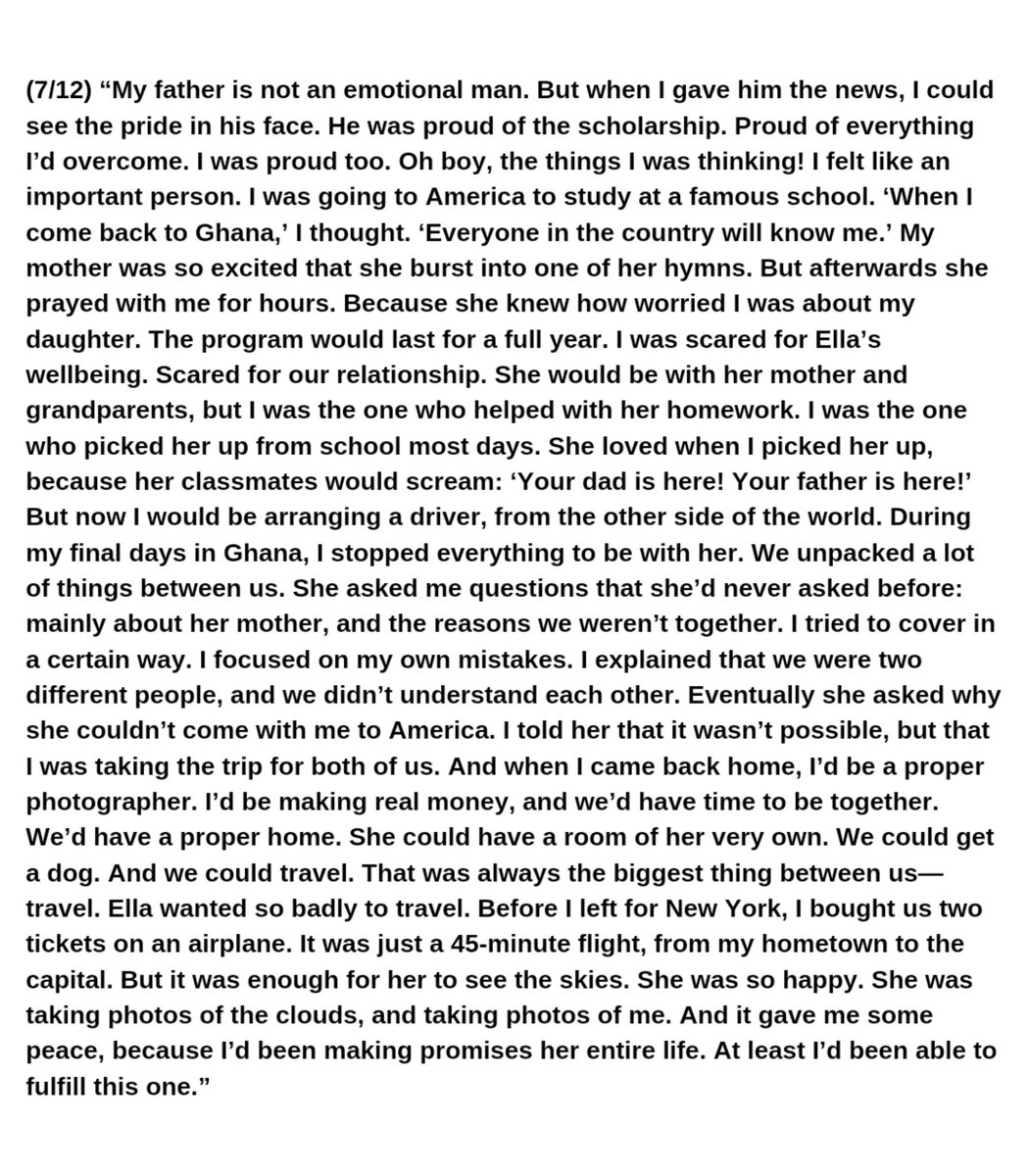

(7/12) “My father is not an emotional man. But when I gave him the news, I could see the pride in his face. He was proud of the scholarship. Proud of everything I’d overcome. I was proud too. Oh boy, the things I was thinking! I felt like an important person..."

(8/12) “When I landed in New York I was full of joy. I spent the first few days exploring the city. I saw places that I’d only seen in photographs: Times Square, Central Park, The Empire State Building. During orientation I met other students from all over the world..."

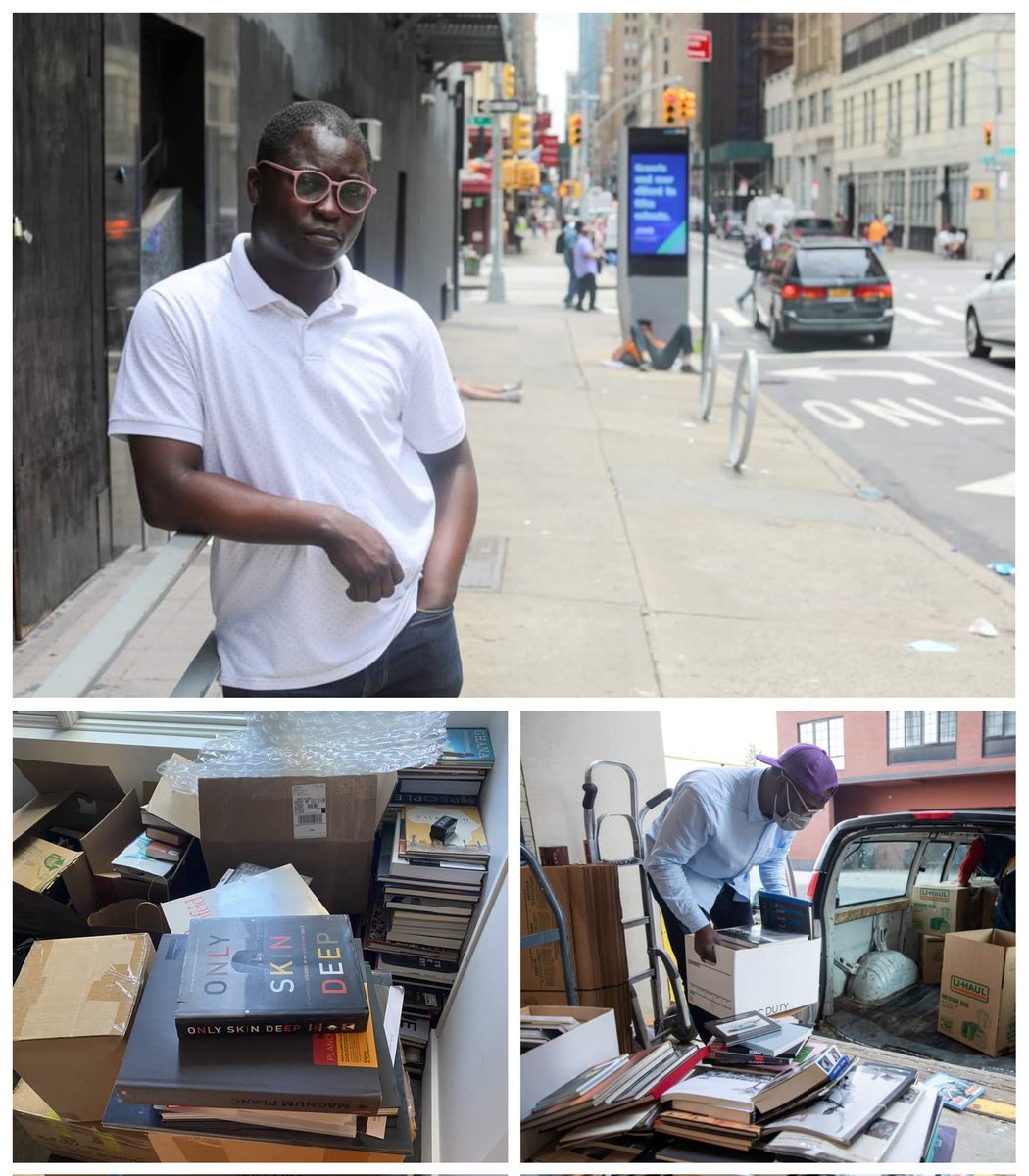

(9/12) “Every day after class I went to the main branch of the New York Public Library. It was my favorite place in the city. I couldn’t believe how big it was. This place had every book in the world. In Ghana I hadn’t been able to find a single photography book,.."

(10/12) “Growing up in Ghana, I’d never once had to think about my skin color. I saw myself as African. I saw myself as Ghanaian. I saw myself as Asante. But never black. Because all of us were black. And to become sensitive to your skin, for the first time,.."

(11/12) “My thoughts grew very dark. It felt like I was wearing new clothes, and I wanted to remove the clothes. But how could I remove my skin? And if I did—what would be left? I tried to push my feelings aside. I tried to switch off my emotions. But this time it wasn’t..."

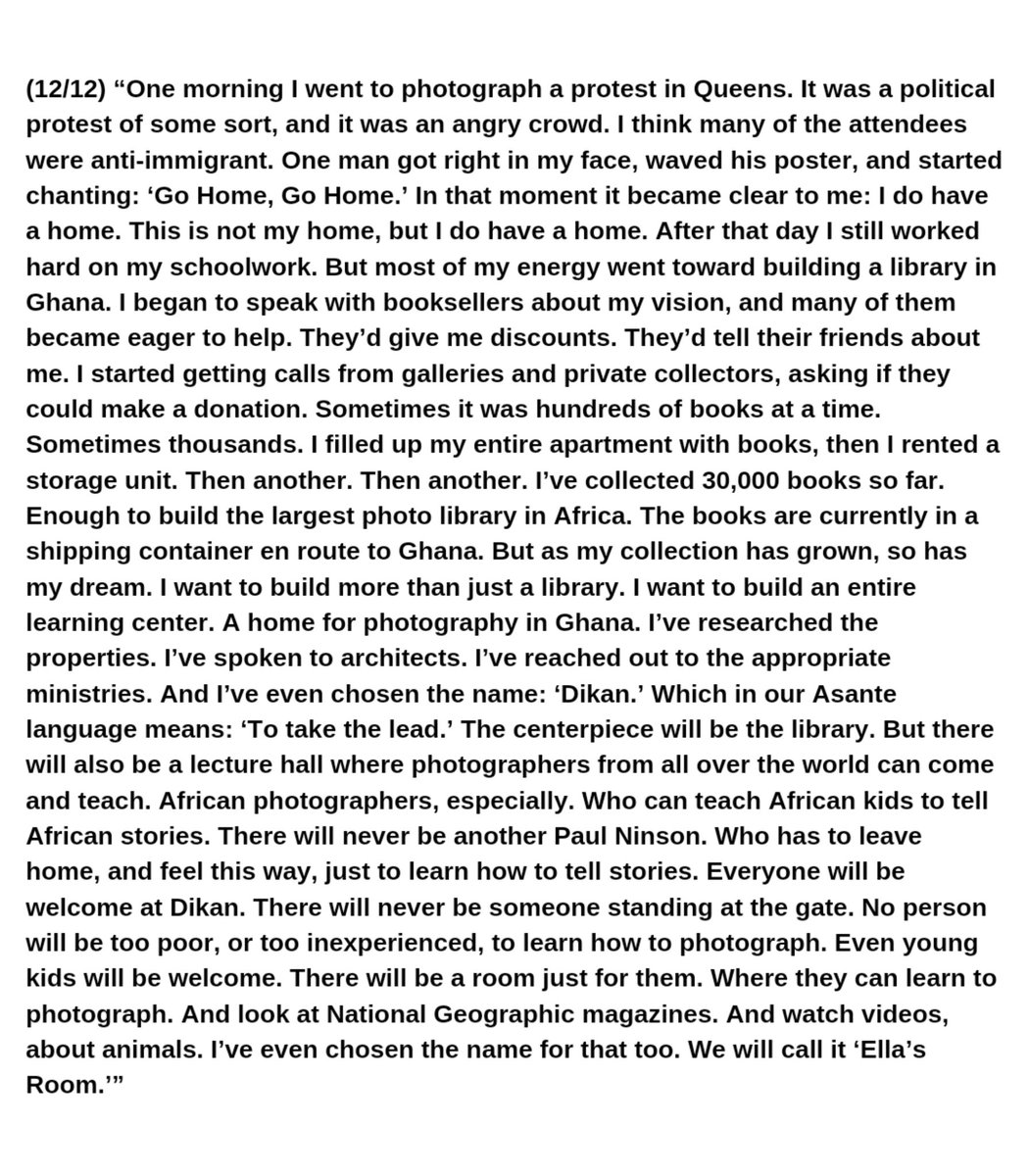

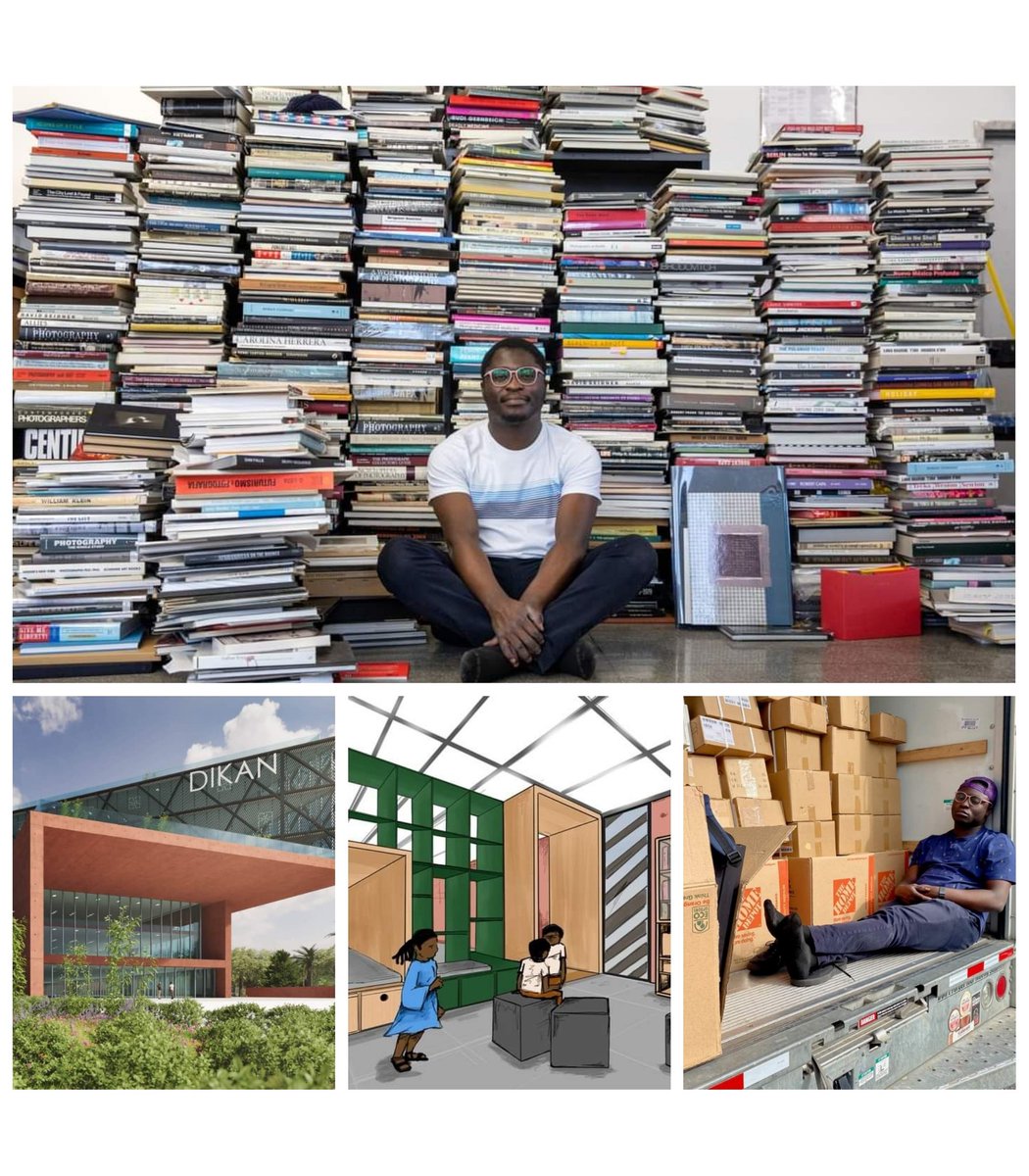

(12/12) “One morning I went to photograph a protest in Queens. It was a political protest of some sort, and it was an angry crowd. I think many of the attendees were anti-immigrant. One man got right in my face, waved his poster, and started chanting: ‘Go Home, Go Home...'"

Let’s Help Paul Build Dikan: bit.ly/letshelppaul

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh