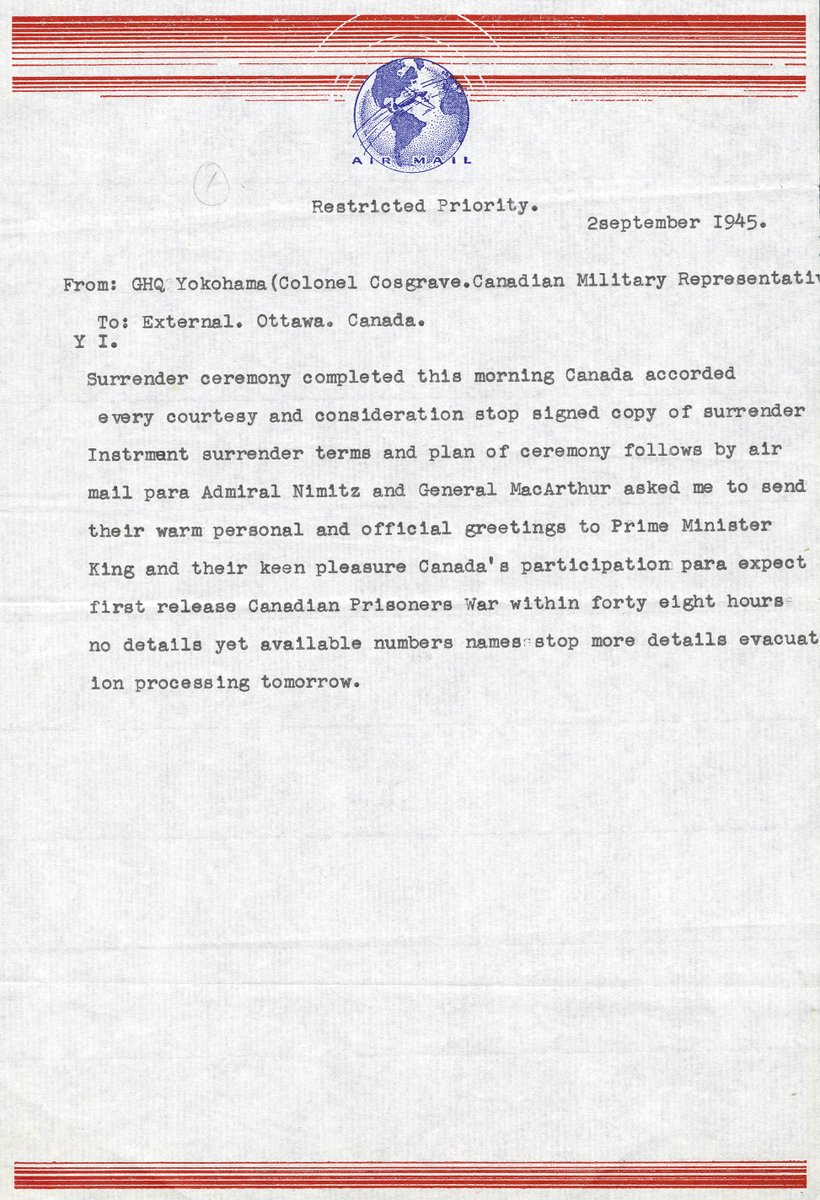

September 2, 1945.

Officials gather aboard the USS Missouri to sign this document and end the Second World War.

Canada’s signature is missing? No. Look closely. We signed on the wrong line.

Officials gather aboard the USS Missouri to sign this document and end the Second World War.

Canada’s signature is missing? No. Look closely. We signed on the wrong line.

Who would make such a blunder?

Well, it could've been anyone, really. We've all done it. Okay, maybe not on an Instrument of Surrender.

This blunder's all Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave.

Well, it could've been anyone, really. We've all done it. Okay, maybe not on an Instrument of Surrender.

This blunder's all Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave.

Who was this Colonel Cosgrave? During the First World War, he saw the gas at Ypres, poppies blowing in Flanders. Two Distinguished Service Orders. The Croix de Guerre.

Wounded in battle, blinded in one eye.

Young men crying for their mothers.

Children singing Silent Night.

Wounded in battle, blinded in one eye.

Young men crying for their mothers.

Children singing Silent Night.

He knew war. He saw it, felt it.

He thought its scourge was over forever.

“...at last, the world was safe for all the babes of the world... which, thank God and the men of to-day, would never again undergo the agony, the pain and the heart torture of another such Armageddon..."

He thought its scourge was over forever.

“...at last, the world was safe for all the babes of the world... which, thank God and the men of to-day, would never again undergo the agony, the pain and the heart torture of another such Armageddon..."

He knew the cost of war. So imagine him that day 76 years ago, half blind from his service. Imagine him signing to end it, committing to human dignity, freedom, tolerance, and justice.

Imagine how he felt in that moment.

Imagine how he felt in that moment.

It's strange how we treat those who make such mistakes, isn't it?

It's strange how we talk about it. It's strange how one mistake stays with them, even in their obituaries.

It's strange we don't ask more about their stories. It's strange we're not more curious.

It's strange how we talk about it. It's strange how one mistake stays with them, even in their obituaries.

It's strange we don't ask more about their stories. It's strange we're not more curious.

He saw the crosses, the poppies.

He tasted the horror of war.

He knew the Dead.

After Ypres, he said Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae laid a piece of scrap paper on his back and wrote this poem.

He tasted the horror of war.

He knew the Dead.

After Ypres, he said Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae laid a piece of scrap paper on his back and wrote this poem.

What would you think of the agony, pain, and heart torture since you signed that document?

What would you say today?

We see you, Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave.

What would you say today?

We see you, Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave.

Since posting this thread, we heard from a member of Colonel Cosgrave’s family who said the eye injury initially occurred while he was boxing at the Royal Military College.

During the war, as per these notes, another injury resulted in a complete loss of vision in the same eye.

During the war, as per these notes, another injury resulted in a complete loss of vision in the same eye.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh