The Advent of Japan - a thread

(1) The Japanese archipelago today is one of old, entrenced cultures, political unity & relative ethnic uniformity. Yet the Yamato - the proper name of those often called simply the "Japanese ppl" - are not the only, nor the first on the islands

(1) The Japanese archipelago today is one of old, entrenced cultures, political unity & relative ethnic uniformity. Yet the Yamato - the proper name of those often called simply the "Japanese ppl" - are not the only, nor the first on the islands

(2) Crucial to understanding any further discussion of Japan's past is the fact that the Yamato, much like the Celts and Teutons of the British isles, arrived in Japan as migrants & invaders - roughly at the same time the first Celts crossed into Britain, in fact.

(3) To begin our exploration of Japan's creation, we have to go back - far, far back, to the cold and desolate world of the Pleistocene, perhaps 40,000 years ago, when the Japanese archipelago was still connected to the mainland, and the first humans reached the area.

(4) Even while land still bridged the archipelago to the mainland, the Japanese region was an isolated place. The genetic split between the first Japanese and the mainland predates that between the East Asians and the folk who first crossed into the Americas.

(5) The word means Jōmon means "cord-marked", and was in fact first coined by American orientalist Edward S. Morse, before being adapted into Japanese. The word refers to their particular style of pottery, the practice of which began in the isles as early as 15kya.

(6) Of the culture of the ancient Jōmon, little can be said with certainty. Quite probably shamanistic, a characteristic of their culture was the production of "dogū"-figurines, typically animalic or, if humanoid, Venus-like.

They lived in pit-houses and limited, tribal units.

They lived in pit-houses and limited, tribal units.

(7) With 40ky of history, the Jōmon would certainly have been not 1 but many cultures & languages. Nor were they utterly insulated, despite their isolation. In their ancestry are traces from maritime East-Asia, including, fascinatingly, Austronesian-related peoples.

(8) The end of the Jōmon period, and, ultimately, their culture and people began not in Japan, but in neighboring Korea. There, 1500 BC saw the dawning of the Mumun period, and with it, the advent of complex agriculture and social hierarchy.

(9) A megalithic culture, the Mumun produced large dolmens like those in Neolithic Europe. They were also the first to import tools and weapons of bronze, though it was not produced locally until 8th century BC. Though not predominating, rice-farming first reached Korea here.

(10) Crucially, the late Mumun period also sees the first appearance of Mumun-like settlements in Japan, on the southerly island of Kyushu. Here, for the first time, is evidence of substantial movement of foreigners into Japan, and with them, settled life and agriculture.

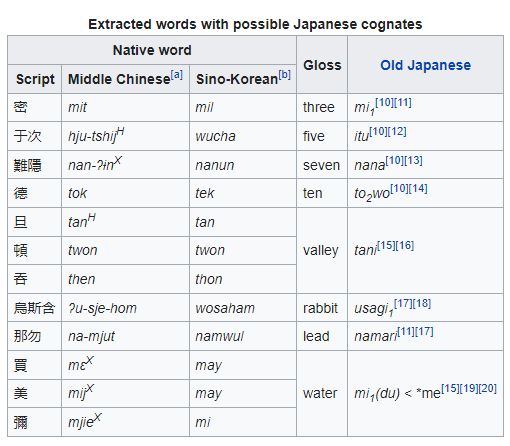

(11) Though linguistic evidence is necessarily scarce here, everything points towards at least the southern parts of the Korean peninsula being the Urheimat of the Japonic languages. Like the insular Celtic languages, Proto-Japonic as we know it likely split post-migration.

(12) The reasons for this migration of early agriculturalist Japonic-speakers across the sea and into Japan are likely diverse and multifaceted, but a very likely factor was the ongoing invasion of Korea by the iron-wielding Kanjin, eventual ancestors of today's Koreans.

(13) This transition is confused by the separate periodisations used by Korean & Japanese, but in Japan, this appearance of identifiably Mumun practices circa 300 BC marks the beginning of the Yayoi period, and with it, the end of the Japanese Paleolithic and the Jōmon period.

(14) I do not have time here to discuss the ultimate ending of the Jōmon people, of their development into the Emishi-tribes and, through admixture with Siberians, the Ainu, nor of the long wars between the Emishi and the rising Yamato empire. This, in the end, was but a prelude.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh