On D-Day, he wrote to the families of men killed by his side. In July, he stepped on a mine, earned the Legion d'honneur. He jumped into Arnhem, swam across the Rhine to escape.

He never forgot the liberation, the letters.

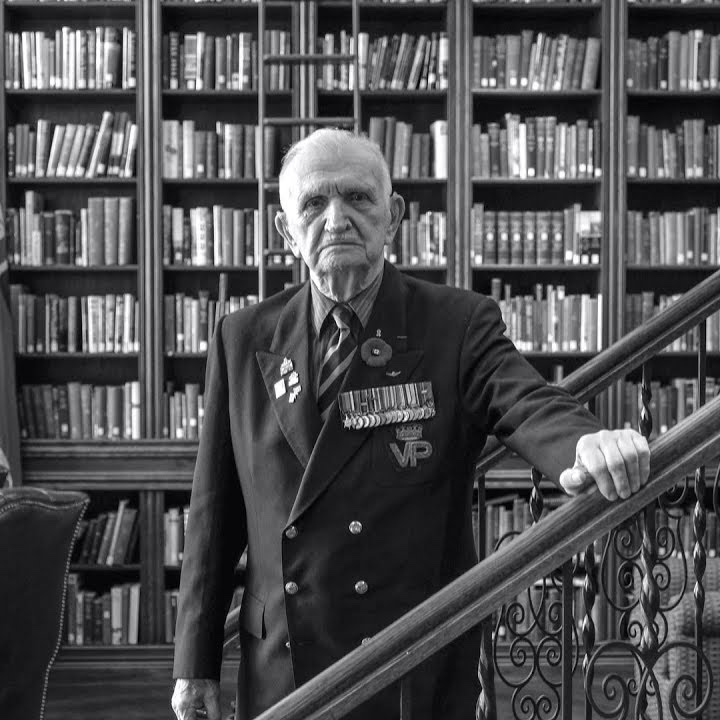

Charles Scot-Brown died Saturday.

Please remember him.

He never forgot the liberation, the letters.

Charles Scot-Brown died Saturday.

Please remember him.

Charles was one of 673 Canadian officers who volunteered for service with British regiments.

He was a fresh-faced 20-year-old officer staring at his Sergeant who had three medals for bravery.

How would he win him over?

He was a fresh-faced 20-year-old officer staring at his Sergeant who had three medals for bravery.

How would he win him over?

By darning socks. Obviously.

After the mine and before Arnhem, he found a familiar face in the hospital in England.

Doreen, a friend from back in Canada, had joined the Air Force. They marry and he returns to the front.

That Christmas, she's writing to him when a German bomb lands on her apartment.

Doreen, a friend from back in Canada, had joined the Air Force. They marry and he returns to the front.

That Christmas, she's writing to him when a German bomb lands on her apartment.

Charles returns to England to bury his wife. Within days, he’s back on a night patrol.

He finds two German soldiers. After some persuasion, he takes them as prisoners.

He finds two German soldiers. After some persuasion, he takes them as prisoners.

That escape swim across the Rhine?

He did it with a wounded soldier on his back.

He did it with a wounded soldier on his back.

By the end of the war, 128 of his fellow CANLOAN officers had been killed and another 337 wounded. Out of 673.

This memorial in Ottawa is dedicated to Charles' brothers who never made it home.

This memorial in Ottawa is dedicated to Charles' brothers who never made it home.

He made it up the beach at Normandy, survived Operation Market Garden, saw the horror of Bergen-Belsen.

Along the way, he wrote letters to the loved ones of those who fell by his side.

He knew the cost of war and wanted you to know, too.

Along the way, he wrote letters to the loved ones of those who fell by his side.

He knew the cost of war and wanted you to know, too.

He remembered the jubilation after the liberation of Holland, the dancing, the joy. He often chose to focus his memory on the lighter moments between the fighting.

"That's the way I programmed myself, so I didn't feel too sorry for myself."

"That's the way I programmed myself, so I didn't feel too sorry for myself."

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh