Nightcrawler’s fantastic difference can resonate with many kinds of Otherness, including disability, racial difference & gender or sexual deviance. This makes him very identifiable. It also makes his objectification very complicated—and fascinating. #XMen @GoshGollyWow 1/11

Beginning in Claremont-penned comics & continuing thereafter, Kurt’s body often becomes an explicit or commented-upon spectacle. One explanation is: Kurt is a sexy character with an exhibitionist streak. But because his body is also seen as monstrous, we need to dig deeper. 2/11

In Excalibur #1, Kurt is objectified in an intimate domestic space for an implied female gaze, actualized by Meggan. This is unusual for male characters. It would be a stretch to say Kurt's feminized, but scenes like this do place him in a stereotypically feminine role. 3/11

But in God Loves, Man Kills, Kurt's objectified differently—as a “freak.” Instead of being gazed at, Kurt becomes subject to what Rosemarie Garland Thomson, in her book Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture & Literature, calls “the stare.” 4/11

Writes Thomson: “If the male gaze makes the normative female a sexual spectacle, then the stare sculpts the disabled subject into a grotesque spectacle. The stare is the gaze intensified, framing [the] body as an icon of deviance.” The stare is dramatically disempowering. 5/11

If we read Kurt as racialized, additional complications attend his objectification. He could be subject to fetishization, his difference desired but only as a set of exotic features to be investigated, possessed, and, ultimately, controlled. 6/11

Yet finding beauty in difference can also be very empowering. This is key to the reclamation of “queer.” Kurt’s deviant body, which includes hard muscles coated with soft fur and a prehensile tail that both thrusts & squeezes, can definitely evoke queerness. 7/11

Kurt's body also evokes changing perceptions of freakishness. Literary critic Leslie Fiedler—who wrote an essay titled “The New Mutants” over a decade before the comic book appeared—argues postwar culture increasingly viewed “freaks” less as Others than “secret selves.” 8/11

But who's looking & how still matters. Scholar Neil Shyminsky argues the mutant metaphor can allow dominant groups to “misidentify themselves as the Other.” Kurt epitomizes this danger; his free-floating difference is ripe for both identification & appropriation. 9/11

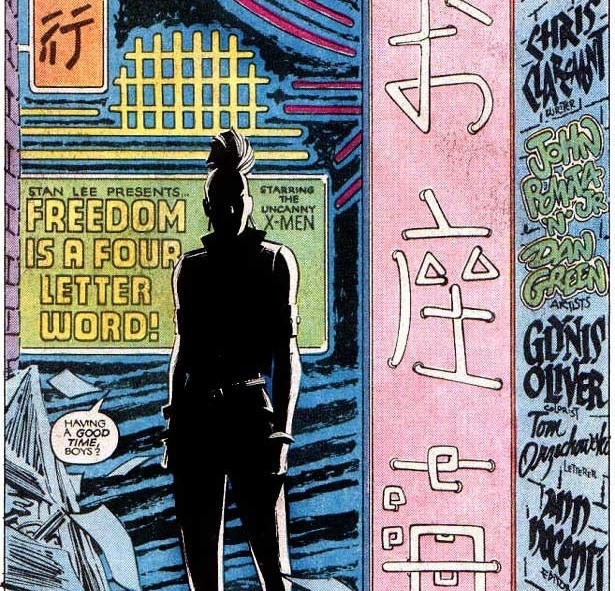

So where does this leave us? What dynamics of empowerment or disempowerment are at play in a scene like this from Claremont & Smith's UXM #169, where Nightcrawler’s demonic body is variously—and simultaneously—comedic & sexy, monstrous & beautiful, touchable & impossible? 10/11

Unpacking Nightcrawler’s objectification requires unpacking objectification. His example is a forceful reminder that no image is singular or binary. Each is a constellation of possibilities to be worked through in conversation with history & culture, ourselves & each other. 11/11

Today’s thread was composed by (e)visiting scholar Dr. Anna Peppard (@peppard_anna). To keep the conversation going, check out the latest @GoshGollyWow podcast on Excalibur #31. It’s not by Claremont, but does feature lots of Nightcrawler. goshgollywow.com/episode-archiv…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh