There’s seemingly a fundamental friction between the progressive and inclusive sexual politics of Kurt Wagner as a person and the (arguably) misogynistic sexual politics of some of the established fictional genres that he fantasizes about participating in. #xmen 1/9

Let’s start by framing this more simply: Kurt respects women. Errol Flynn movies and John Carter novels tend to frame women as sexual trophies devoid of agency. I’m not saying these stories are bad or anyone is wrong to like them, just that the female characters are objects. 2/9

There are two ways then to approach this friction: either Kurt is a hypocrite, or there is a layer of irony that we can locate within his participation in these genres, one that might even hold the potential to produce critical insights int the tropes those genres perpetuate. 3/9

We could, for example, compare his participation in these genre fantasies to Bakhtin’s concept of “carnival,” (a liberating, indulgent experience) or Riviere’s concept of “masquerade” which sees one performing extreme stereotypes in order to subvert them. 4/9

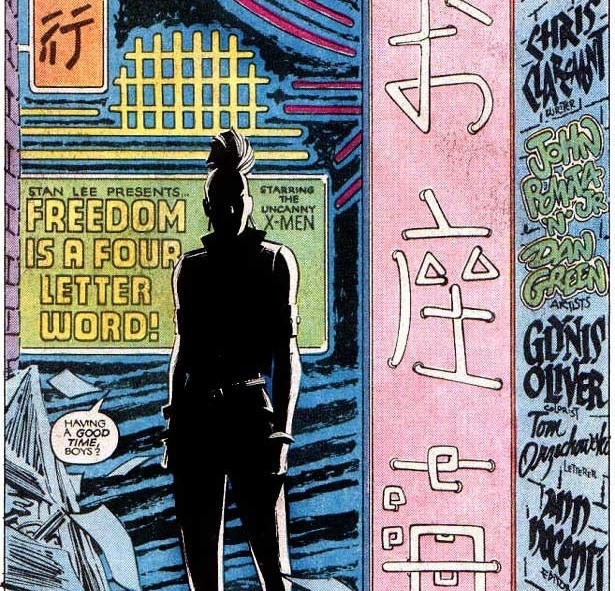

Irony is perhaps most easily located in self-awareness. When Kurt swashbuckles (for lack of a better term) he tends to have what my father-in-law would have referred to as a “shit-eating grin” on his face. When he swoops women into his arms, they tend to giggle not swoon. 5/9

Kurt also tends to adopt over-the-top dialogue and postures, thus signaling that his participation is indeed a performance, whilst including women into that performance through the shared recognition that he projects. This shows both awareness, then, and irony. 6/9

That inclusivity is especially important for genres that tend to exclude women (both as characters and as audience members). Women aren’t always allowed to swashbuckle, but Kurt holds that door open for them, even switching gender roles at times. 7/9

This is not a vindication of Kurt’s fantasies, however. The lines between fantasy and reality are blurry and malleable within the subjective perceptions of individual readers. Even his admiration for these genres could potentially make someone feel unsafe, for example. 8/9

Ultimately, I guess my point is that this aspect of his character can either be delightful or troubling, critical or worthy of criticism. It doesn’t speak to a unified position or politics, but to the paradoxical internal conflict of human fantasy at large. 9/9

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh