Today in pulp I ask the question: what does life actually want, and what does this tell us about the superintelligent robots that will dominate the future?

Yes it’s time for some pulp-inspired idle musing. Twitter’s good for that…

Yes it’s time for some pulp-inspired idle musing. Twitter’s good for that…

First off: full disclosure. This is a live thread in which I’m thinking aloud. It will doubtless meander, cross itself and end up in knots. “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself” as Walt Whitman used to say.

But the coming Singularity, when computers undergo an intelligence explosion and leave us in the intellectual undergrowth, remains a dominant idea in modern sci-fi. Much of which is very entertaining and well written I might add.

But… it has a problem. We keep on going round the same ideas loop when we discuss the Singularity. In the world of AI we are all Rationalists and Systems Thinkers: Turing and von Neumann are our sages.

You’ve no doubt encountered Rationalist views about AI. Many popular science books on machine intelligence reference their ideas, and if you’re interested you’ve probably visited Astral Codex Ten on Substack or the Slate Star Codex archives online.

And it’s all good stuff: tasty, heavy and filling like a traditional French dinner. It’s also sometimes alarming: there’s always someone worrying that the Singularity will - by accident, design or capriciousness - end up destroying humanity.

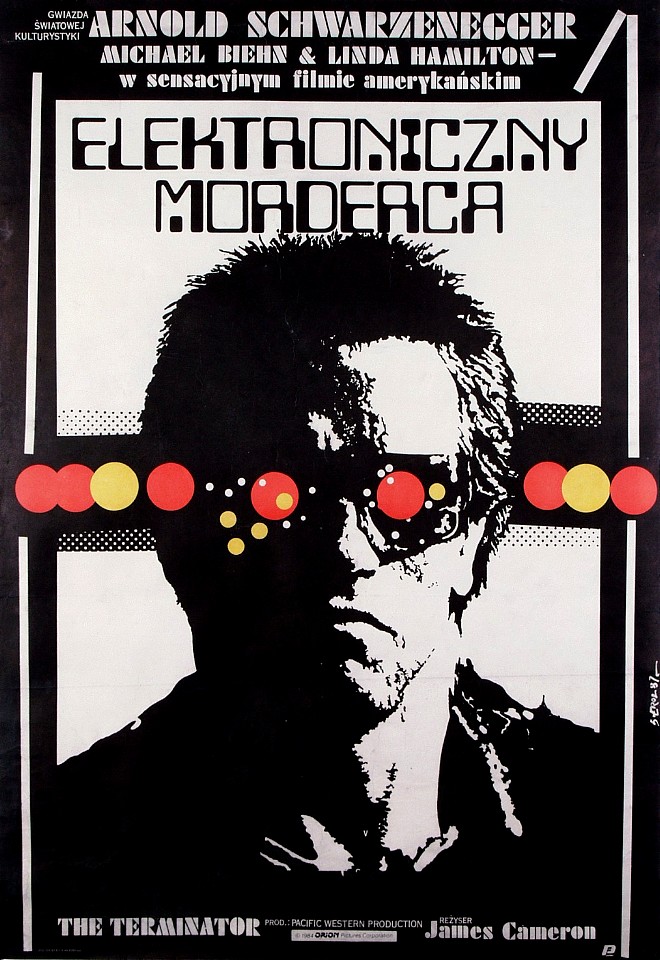

At this point please put all ideas about The Terminator out of your mind. Nobody’s that worried about SkyNet (though many are concerned about lethal autonomous weapons systems, probably with good reason).

Nor will a super AI muse upon existence and quickly figure out that humans are a warlike, illogical threat and put us out of its misery. That's a good sci-fi plot, but not really a plausible outcome of general artificial intelligence.

No, our doom will come because the Singularity will pursue some goal we set for it that ends up contrary to our own. Our old friend the Law of Unintended Consequences will be our downfall.

A popular, though silly, example is the Paperclip Machine. Imagine we create a supercomputer and tell it to make paperclips. Because it does nothing else soon it turns you, me and everything else is turned into paperclips, or paperclip factories.

Universal Paperclips is a fun game you can download to play out this exact scenario. But are there any scenarios - any goals - we could set a supercomputer that wouldn’t end up with deadly unforeseen consequences for us?

This argument is regularly discussed across various internet fora and in many excellent novels and short stories. However it does seem to come with an inherent bias: one which, like Bananaman, I am ever alert for…

🚨GAME THEORY KLAXON!🚨 Yes it’s our old friends Utility Maximisation and Bayesian Decision Theory. Discussions of the Singularity and its possible threat to us keep coming back to game theory like it was its own Nash equilibrium. In AI terms it’s the only game in town.

Or is it? Is there another way to think about super-powered AI, other than thinking about goal-directed behavior and initial conditions set up on a Turing machine? What happens if we think another way? Do we come up with some different alternatives?

Now you might think I’m going to go off on a long discussion about ‘what is intelligence?’ Why would I do that? You can go to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and read all about it there.

No, I’m going back to the ocean…

No, I’m going back to the ocean…

In particular to a hydrothermal vent on the ocean floor some 4.5 billion years ago. That’s where (possibly) the first life on Earth emerges. A place rich in H2, CO2 and iron, with a natural energy gradient and lots of porous rocks.

It’s possible/probable that life’s origins on Earth lie here. An anaerobic organism creating adenosine triphosphate in the holes of the porous rock. A thing on the edge of life, a fizzing energy machine in a stone crucible in the dark.

Now somehow - we don’t know how - this thing develops both the ability to create a boundary around itself and the ability to create its own energy gradient, along with a circular chromosome. It becomes a bacterium!

Then things get weird…

Then things get weird…

Bacteria are brilliant at reproducing themselves, using binary fission to quickly create myriad copies of themselves. If the point of life is to pass on your genes then bacteria are reproductive superstars. You wouldn’t need anything else, they’re perfect for the job.

But there are other things in this world: amoebas, daffodils, pandas. Things which aren’t quite as efficient as reproduction. What gives? What’s the point? Life is about reproduction and the bacteria are the winners.

Well it looks like something else drifted away from that hydrothermal vent as well as the bacteria. Eukaryotes! They may look like bacteria, but they’re not. They have a special feature: their cell nucleus is surrounded by a membrane and they seem to have a longer genome.

Pretty soon (OK, a million years or so) the eukaryotes are looking pretty complex. Then they pull out their party piece: they become multicellular. OK, so do some bacteria, but the eukaryotes are way better at it. In fact they just can’t stop.

You, me, your dog, your dinner, that pigeon in the garden: we are all very big eukaryotes. Which is odd. In terms of survival and reproductive fitness the bacteria seem to be better than the eukaryotes. So why are we still here?

🚨NATURAL SELECTION KLAXON!🚨 There are many niches that life can occupy on Earth and some are favourable to complexity. And as life itself alters the characteristics of the Earth there is space for more than just bacteria to live and thrive in.

But… something else also seems to be happening along the way. Some evolutionary adaptions don’t seem to be the direct byproduct of adaptive selection. Life evolves funny things that don’t hamper its survival but aren’t always the best idea. Yet they persist, and are passed on.

Structuralist biologists call these things spandrels, and they can be controversial. If you evolve a third leg it has to have some use, otherwise why would it persist in the species? Natural selection always weeds out the unnecessary.

The question may be when does the spandrel acquire a utility value that makes it favourable, and therefore selected for. A third leg may be useless at first but if it eventually mimics a tail then that’s quite a useful thing.

And that brings us back to Artificial Intelligence. Some people (and I’m not looking at you Chomsky) suspect that some of our ‘higher’ human attributes like language may have started out as spandrels. At first they’re not detrimental but not obviously advantageous…

...but given time they can be evolutionary dynamite! Language helps you adapt to the environment in real time. It encodes and passes on information faster than trial and error or operant conditioning can. It’s good stuff.

And you can possibly make the case that general intelligence and higher order thinking might be the same: a spandrel that turns out eventually to be a brilliant adaption. As I say, it’s a subject full of arguments, counterfactuals and the occasional ‘just so’ story.

It also leads to… 🚨MEME ALERT!🚨 Yes, Dawkins’s idea of a unit of cultural transmission that evolves through a type of natural selection. The idea that memes, rather than logic, is the true backbone of ‘intelligent’ behaviour is a theme in many rather jolly Cyberpunk stories.

And if you believe in a future of uploading consciousness to The Cloud and living forever as an avatar it certainly may play a part in your future cyberpunk existence.

But what’s all this got to do with The Singularity?

But what’s all this got to do with The Singularity?

Our exam question is this: will a superintelligent computer wipe us out through the Law of Unintended Consequences if we ever enable it to exist? Does our choice of goal directed behaviour and initial conditions for our AI decide whether it will be benign or lethal?

Game theory may give us one set of answers, but evolutionary biology may suggest the problem is rather different. As the AI rapidly grows it probably (but not certainly) evolves. And we assume inherent goals and initial conditions bias the evolutionary path it takes.

If the AI takes the bacteria route… it’s bad news. It becomes super efficient at its basic function and it changes its environment to better fit its goal. We all turn into paperclips.

But if the AI takes the eukaryote route, if it explores the niches available in its environment, if it develops spandrel attributes… maybe it becomes an AI that favours complexity over efficiency. Maybe we don’t all become paperclips.

Maybe, just maybe, there is an evolutionary bias towards exploring complexity - all other things being equal. Maybe a thing that can survive doesn’t lose out by investing some evolutionary capital in becoming more complex, even if that makes it less efficient in the short term.

In which case it may be predisposed to nurture other complex systems, like flowers and badgers and the ozone layer, and even us. That would make AI a natural part of the Gaia paradigm, which would make James Lovelock very happy!

More late night musings another time...

More late night musings another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh