In January 1919 a new magazine heralded the dawn of the Weimar era. Its aesthetic was a kind of demented Jugendstil, and its stories were dark gothic fantasies.

This is the story of Der Orchideengarten...

This is the story of Der Orchideengarten...

Der Orchideengarten: Phantastische Blätter (The orchid garden: fantastic pages) is probably the first ever fantasy magazine. Published in Munich by Dreiländerverlag, a trial issue appeared in 1918 before the first full 24 page edition was published in January 1919.

"The orchid garden is full of beautiful - now terribly gruesome, now satirically pleasing - graphic jewelery" announced the advanced publicity. It was certainly a huge departure from the Art Nouveau of Jugend magazine, which German readers were already familiar with.

Der Orchideengarten was founded by two Austrian writers: Karl Hans Strobl, who had published a 1917 collection of horror stories called Lemuria; and Alfons von Czibulka, a Bohemian-born artist and writer. Both had moved to Munich after the Great War.

Der Orchideengarten focussed on fantastic, occult and erotic literature. As well as original German stories the magazine carried translations of tales by Voltarie, Dickens, Guy de Maupassant, Poe and Hoffman amongst others.

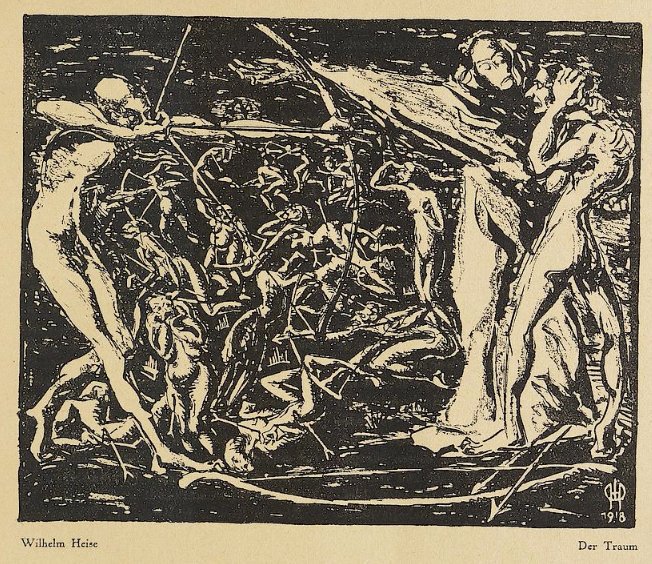

Interior illustrations in Der Orchideengarten had many influences, from traditional woodcut prints to Art Nouveau. Artists included Alfred Kubin, Wilhelm Heise, Alfred Ehlers and Edwin Hemel.

The shattering effect of the Great War is evident in the style of the early Orchideengarten covers. Issue three has a gaping dragon's mouth against a dying sun, devouring a chain of corpses. Rolf von Hoerschelmann's interior illustrations reflect the horror of no man's land.

Later issues of Der Orchideengarten have a more everyday macabre slant. Here is Otto Pick's cover illustration for the December 1919 edition, for the story Das Tödliche Abendessen by Karl and Josef Kapek.

By 1920 the range of styles used by Der Orchideengarten had broadened. A sly humour had begun to creep in to the magazine along with a wider range of topics. Themed issues, such as "fantastic love stories" or "electric demons" were also published.

Problems dogged Der Orchideengarten: issue were withdrawn from circulation due to their lewd nature, sales were lower then needed, the price quickly rose from 80 pfennigs to 2 marks whilst the page count decreased. The magazine finally closed in November 1921 after 51 issues.

Whilst it was a niche publication, Der Orchideengarten illustrates how quickly things were moving artistically in Weimar Germany: from the chaos of the November Revolution to the cabaret of early 1920s Berlin.

The ever-excellent archives of the University of Heidelberg have full scans of Der Orchideengarten: digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/orchide… …… Do take a look if you have the time, and do explore their collection of other Weimar titles.

More stories another time...

More stories another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh