With every new WEO come a gazillion new ideas to reflect on and write about. This is no summary of the main points, but some of the data points I found particularly interesting. A thread on the @IEA WEO 2021:

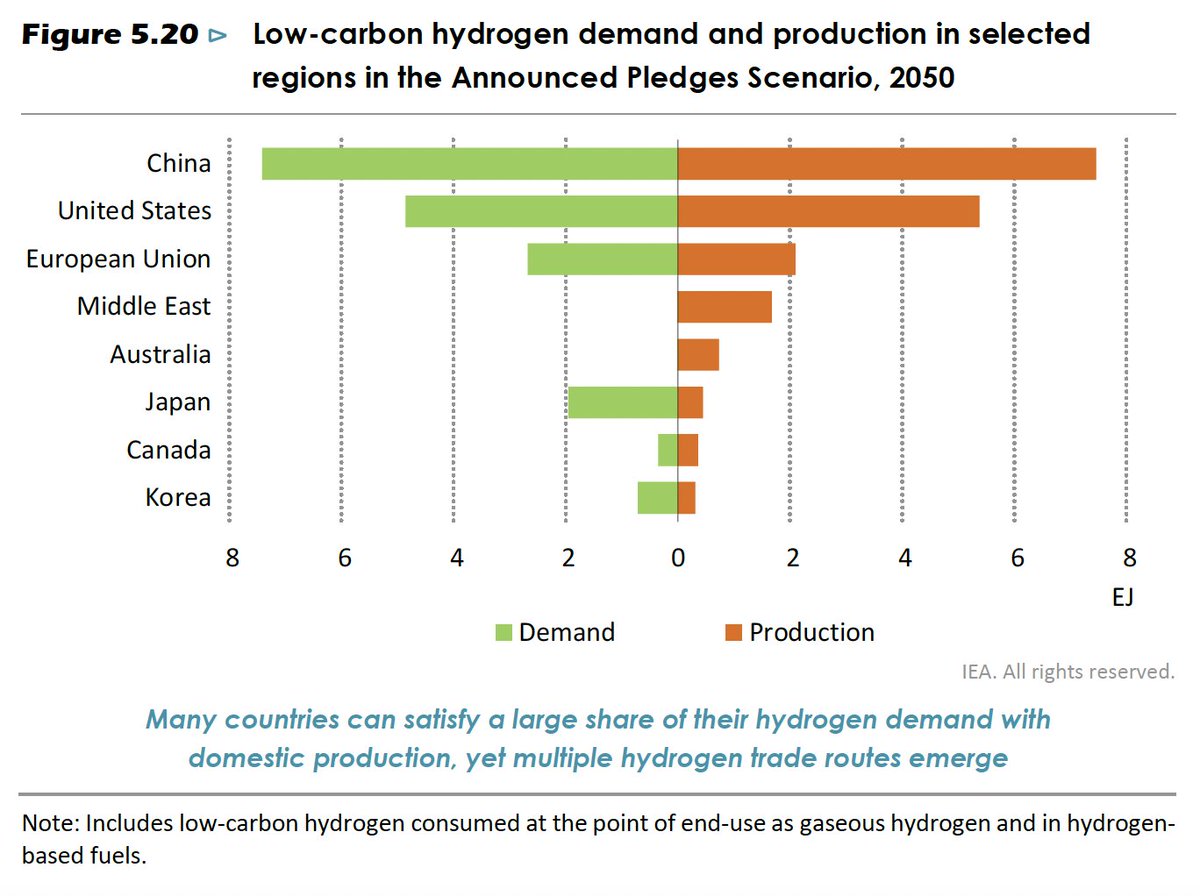

First, we are witnessing a profound transformation in the geopolitics of energy. By 2050, the geopolitics of energy will mean critical minerals and hydrogen rather than oil and gas. This is what we will trade. This is a big part of what we will need to manage across borders.

Having said that, the geography of hydrogen will not merely follow the geography of gas. It is too soon to speculate on trade routes for hydrogen by 2050, but this graph makes a key point: hydrogen trade routes will likely be limited. Think about hydrogen in its own terms.

Oil, gas and coal are far more diversified markets than many critical minerals. But this also begs a question: is there an inverse relationship between size and concentration? I think there is. The concentration problem will lessen over time. But only with our hard work.

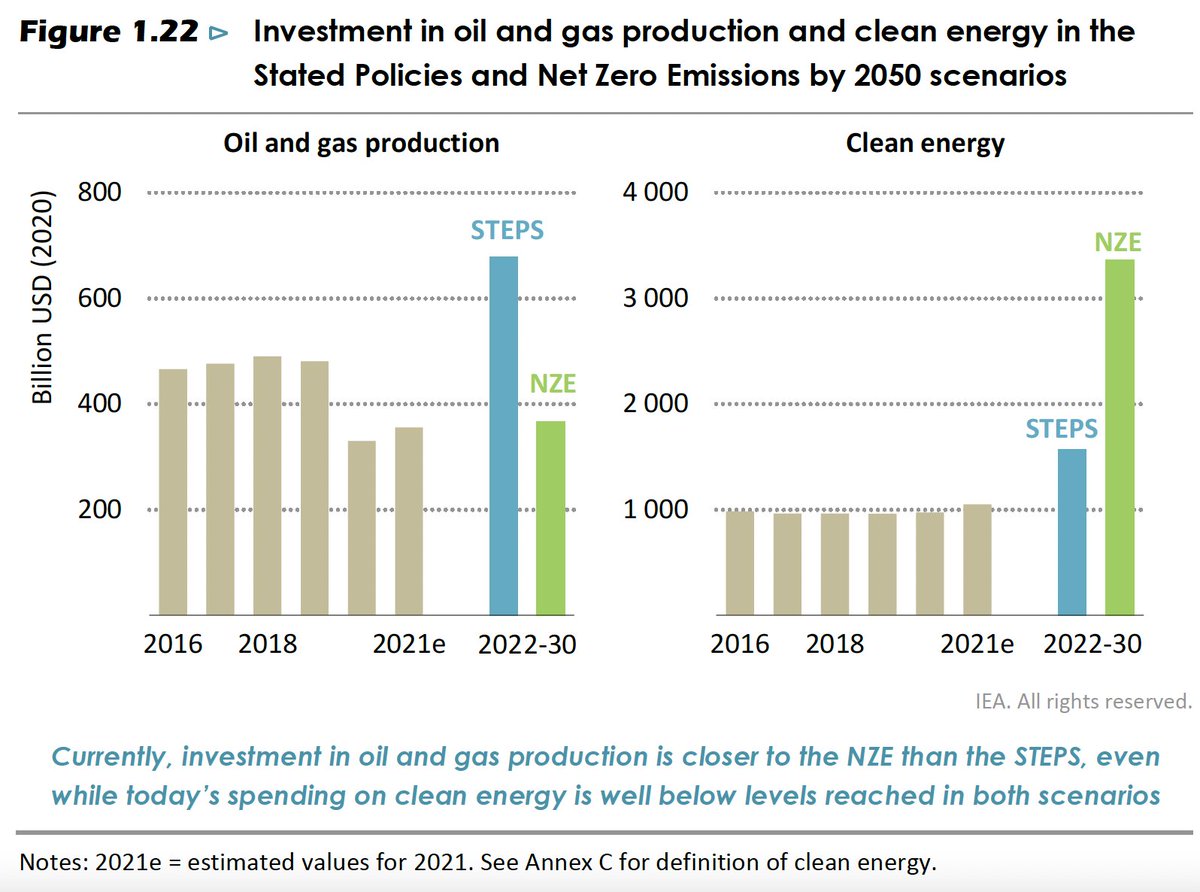

This chart also struck me. The scales are different so don’t rush to read it, but it makes a crucial point close to my heart: de-capitalizing oil and gas is not the same as capitalizing clean energy. Those are two distinct things. And the gap for clean energy is *huge*.

There are so many jobs associated with the energy transition. But there are also major job losses, often in different places. More than 4 million jobs in oil, gas, and coal lost by 2030 in a net zero path. An immense challenge for the just transitions community.

I couldn’t help but pause as this graph. We need nuclear to step up. Not just in emerging economies but in advanced economies too. And just to maintain what we have—to build new reactors. What a challenge.

This graph is also striking. Based on the news, it seems like the moment of hydrogen and CCUS. Yet when you look at the announced pledges versus the trajectory for a net zero world, there is a huge gap. We have barely started the hydrogen and CCUS journeys.

Finally, two images on water stress and physical infrastructure. It is an interplay we are only beginning to fully digest—and water is just one stressor. What we have is not secure for the world that’s coming. This is a map to print and put on one’s wall.

As ever, this is an immense piece of scholarship and the starting point for any serious discussion about what we need to do. So many ideas to come back to. Huge congratulations to @Laura_Cozzi_, @tim_gould_, and the whole @IEA team under @fbirol.

PS. Don't miss the IEA data visualization appreciation tweet:

https://twitter.com/ntsafos/status/1448245082113576967

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh