For folks who can't make my #rEDSurrey21 presentation on developing expert teaching, here's a short summary:

↓

↓

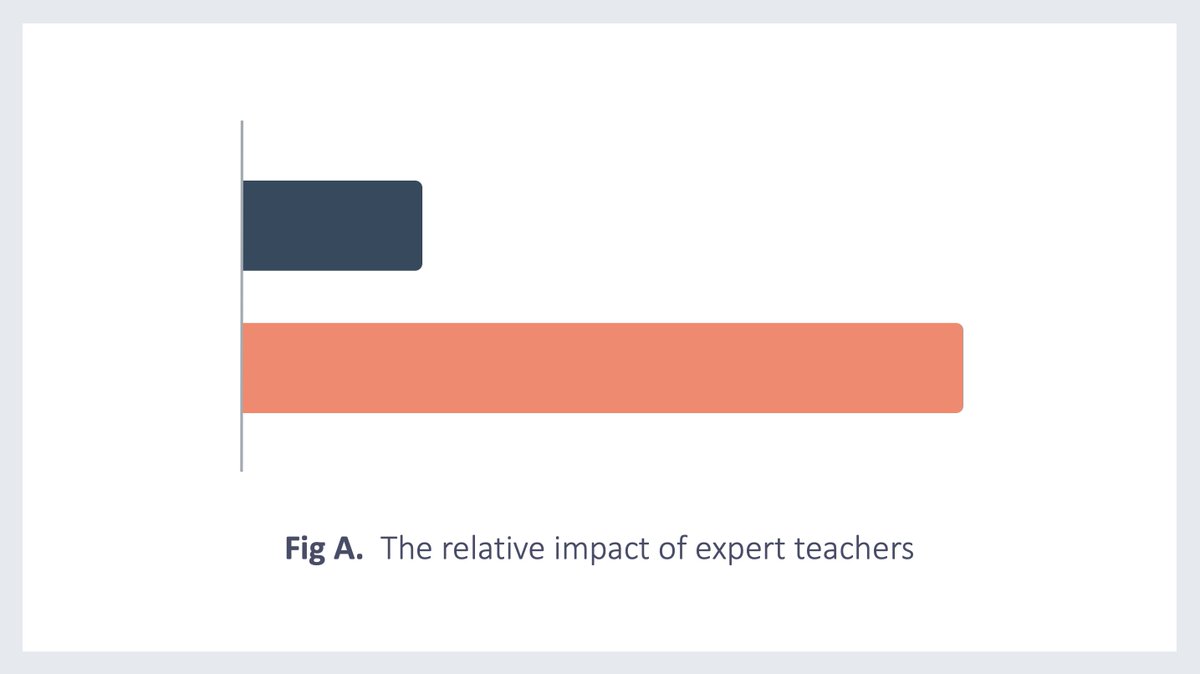

The most expert teachers help pupils learn 4x faster than the least expert (Wiliam, 2016).

Teaching expertise is a thing worth investing in.

Teaching expertise is a thing worth investing in.

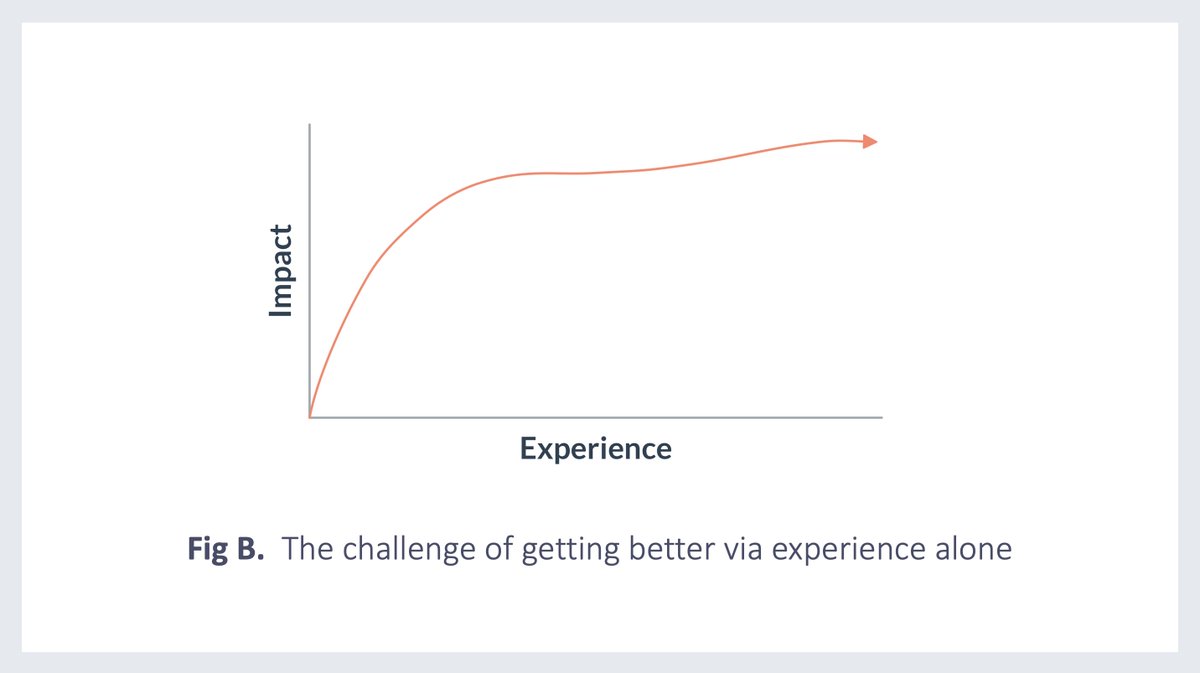

However, getting better at many aspects of teaching is hard to do via experience alone (Kraft & Papay, 2016).

This is why formal teacher development is so important.

This is why formal teacher development is so important.

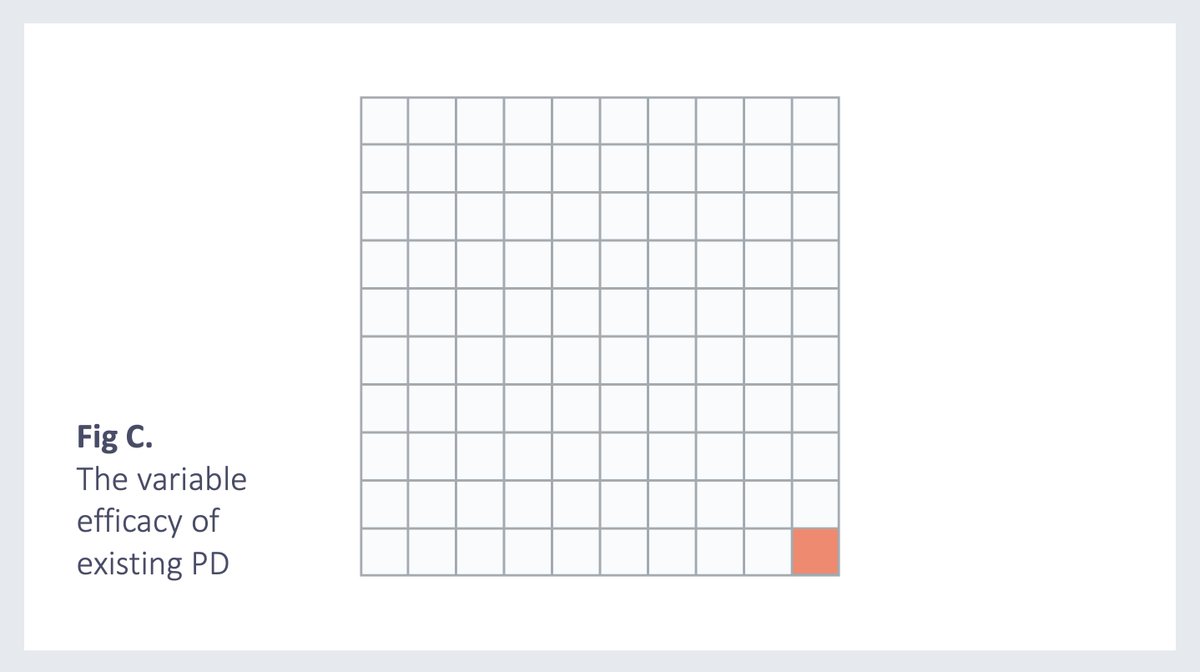

However, the quality of teacher development is highly variable. There are a few bright spots, but most programmes have little impact, and some are even detrimental (Fletcher-Wood & Zuccolo, 2020).

There's room for improvement.

There's room for improvement.

For me, improvement begins with establishing clarity around:

→ What expertise is

→ How we can systematically develop it

→ What expertise is

→ How we can systematically develop it

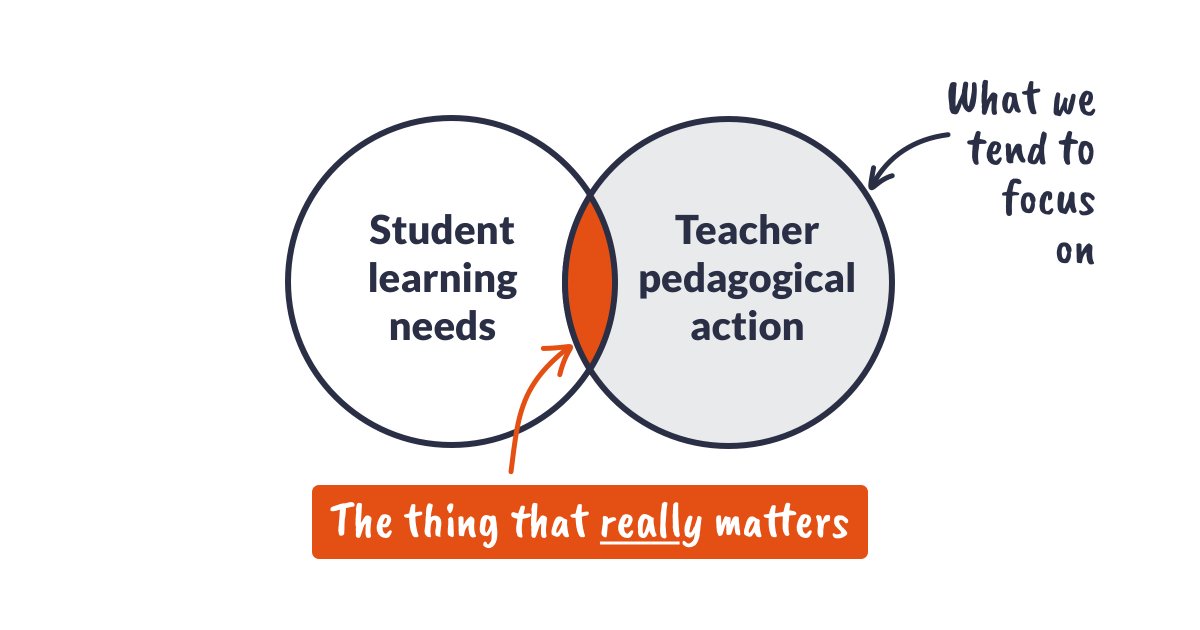

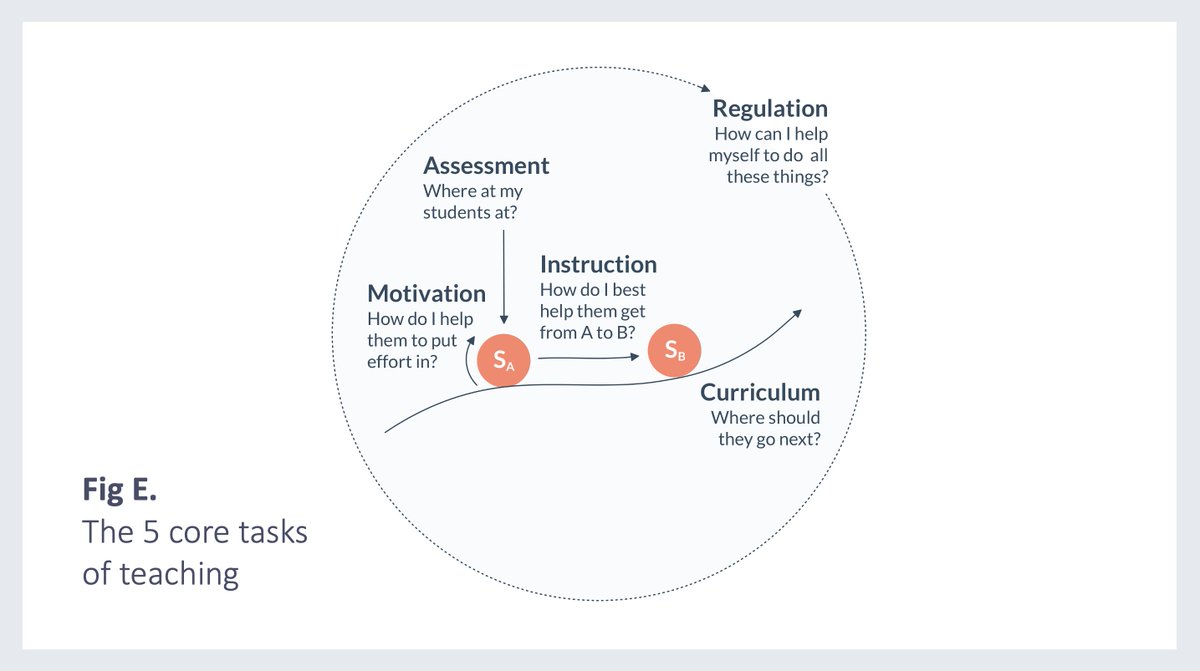

Expertise is reliably strong performance against the core tasks that a teacher faces (Ericsson et al, 2018).

While the core tasks of teaching are the same for every teacher, the strategies needed to tackle them are unique.

While the core tasks of teaching are the same for every teacher, the strategies needed to tackle them are unique.

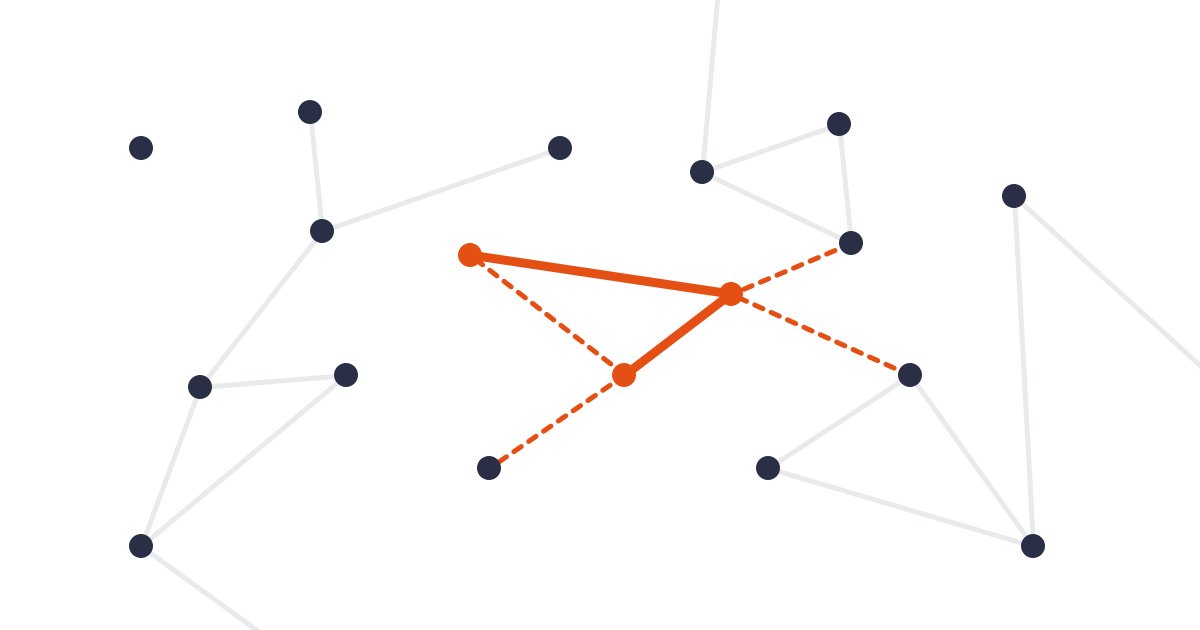

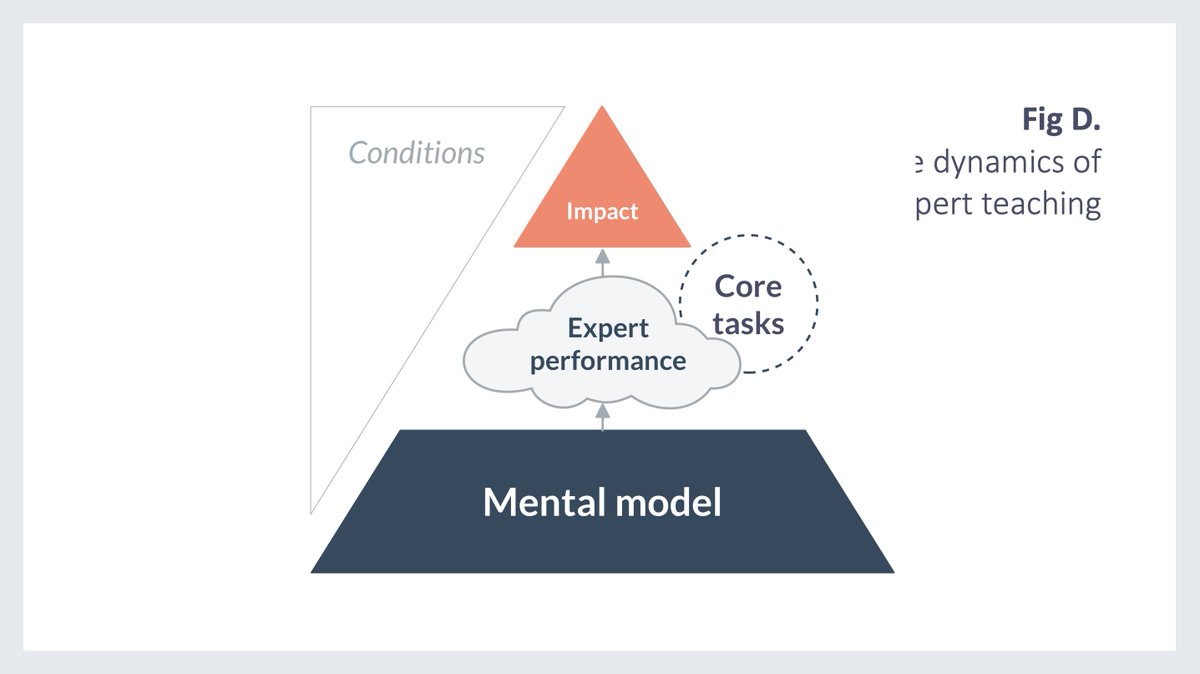

Our ability to tackle the core tasks of any role is a product of the 'mental model' that we possess.

'Mental model' is just a fancy term for 'what teachers know and how that knowledge is organised to guide perception, decision and action'.

'Mental model' is just a fancy term for 'what teachers know and how that knowledge is organised to guide perception, decision and action'.

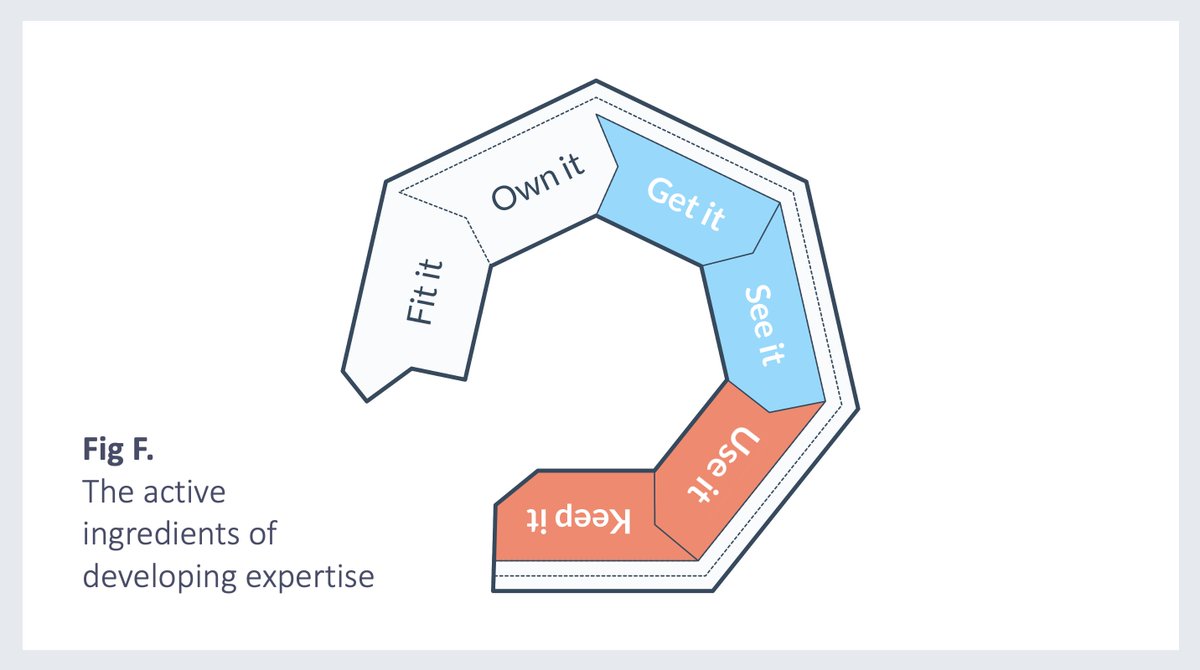

We can systematically build teaching expertise around these core tasks by employing a set of essential development processes (or 'mechanisms').

👊

👊

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh