At this moment 266 years ago the ground began to shake in the Portuguese capital, marking the start of the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755, a catastrophe which costs thousands of lives, revolutionized European philosophy and kicked off a new era of enlightened urban planning.

Mid-XVIII century Lisbon was one of the most beautiful — and wealthy — cities in the world. As capital of the vast, Portuguese empire, it was the major port through which spices from the East Indies, ivory from Africa and gold from the Americas entered Europe.

As a series of remarkable paintings from the renaissance show, Lisbon was a cosmopolitan metropolis in which people from throughout the empire intermingled and did business together.

Wealthy merchant families built grand palaces throughout the city, though none was as magnificent as the riverfront Paço da Ribeira, seat of the Portuguese royal court since the early XVI century.

The palace was commissioned by Manuel I (1469-1521), the legendary Portuguese king who oversaw one of the key periods of the country's overseas expansion and financed Vasco da Gama (who discovered the sea route to India) and Pedro Álvares Cabral (route to Brazil), among others.

Manuel insisted on moving the royal residence from the old São Jorge Castle, up on eponymous hill, right onto the banks of the Tagus River, at a spot where incoming caravels could literally pull up and unload cargo from far-off corners of the world.

Indeed, the bottom floor of the palace was the headquarters of the Casa da Índia, which simultaneously served as a customs house / accounting administration for the empire's trading posts, an archive / warehouse, and as the main office of the world's first global postal network.

The original Paço da Ribeira was built in the Manueline mode, a Portuguese architectural style that mixed late Gothic and Luso-Moorish elements with iconography that evoked the sea and celebrated the (then cutting-edge) maritime technology of the era.

Nothing from that palace has survived, but we know from period sketches that it was decorated with the armillary spheres that Manuel associated with his reign. Designed to show the movement of the stars around a stationary Earth, the spheres were used by mariners on expeditions.

Side note: I think it's fascinating that Manuel incorporated the armillary sphere into his building décor, as the modern equivalent to such a move would be for us to place images of satellites or equally groundbreaking technology into our own architectural flourishes.

In the West we seem to have done quite a bit with it during the 20's and 30's, but quit it during the latter half of the XX century. The Soviets kept it going awhile longer, but I don't think anyone is doing it today. Bit sad really.

Anyway, back to the palace and the earthquake and all that.

When the Spanish took control of Portugal in 1580 (long story that we don't need to get into now), Phillip II (1527-1598) started spending long periods in Lisbon, where he felt at home (his mother was Portuguese).

When the Spanish took control of Portugal in 1580 (long story that we don't need to get into now), Phillip II (1527-1598) started spending long periods in Lisbon, where he felt at home (his mother was Portuguese).

He set about majorly improving the existing palace, which he expanded and "ennobled" with entirely new levels, a grand tower, and fortifications to keep it, and the main riverfront square, safe from any waterborne attacks.

Although Phillip II doted on Lisbon, his sons Phillip III (1578-1621) and Phillip IV (1605-1665) largely ignored their Portuguese subjects.

Phillip III only visited the city — and the riverfront palace — once and insulted the locals by exclusively hanging out with Spaniards.

Phillip III only visited the city — and the riverfront palace — once and insulted the locals by exclusively hanging out with Spaniards.

Timid Phillip IV didn't ever visit; indeed, his only significant, remote interaction with Lisbon came in the form of his financing a festival to commemorate the canonization of Saint Isabel of Portugal (festivities which are still celebrated today).

That doesn't mean the Paço da Ribeira was empty or neglected. On the contrary, it was home to a series of viceroys who ruled on behalf of the Spanish king, and the grand square it faced — the Terreiro do Paço — was very much the center of Lisbon's civic life.

While day to day commerce and special events, like bullfights, happed in that square, major industry was undertaken on the other side of the palace, where a great drydock occupied the Ribeira das Naus.

To the right of the palace square (seen here in this model housed at the excellent @MuseudeLisboa) you had the medieval town that had risen within the old Moorish city walls, and the later fortifications put in by King Fernando in the XIV century, a labyrinth of narrow streets.

To the left, in areas both within and outside the walls, and within what is now the Encarnação neighborhood, Portugal's wealthiest families had built their palaces for easy access to the viceregal court. Those homes gained greater strategic importance after 1640...

...The year in which Portugal regained its independence from Spain when the local nobility rose up, took viceroy Margaret of Savoy hostage, and threw her lead advisor, Miguel de Vasconcelos, to his death out of one of the palace windows.

With independence restored and the House of Bragança now on the throne, Lisbon entered a period of renewed splendor, with the Paço da Ribeira — and its square — once again serving as the heart of the global empire.

The Bragança's sponsored major public works projects in Lisbon, from the spectacular Águas Livres Aqueduct to the Menino Deus Church, to the grand Opera do Tejo, the opulent royal theatre which opened in March of 1755.

But all that wonder literally came crashing down on that morning 266 years ago. November 1 is the Feast of All Saints, and in Catholic Lisbon that meant that everyone was at church, lighting candles for the dearly departed when the 8.4 magnitude earthquake struck.

To get a grip on just how intense this earthquake was, you have to understand that its epicenter was in the Atlantic, about 290 kilometers from Lisbon, but its intensity was still such that it managed to damage the main tower of the cathedral in Sigüenza, in central Spain.

In Seville the tremors destroyed 6.5% of homes and left 89% damaged, and it caused the Giralda tower to partially collapse.

In Madrid the shaking was such that a stone cross broke off from the façade of the Buen Suceso church and fell on two children, crushing them to death.

In Madrid the shaking was such that a stone cross broke off from the façade of the Buen Suceso church and fell on two children, crushing them to death.

Further down, on Spain's bit of Atlantic coast, the effects were even more dramatic. To this day, visitors to Matalascañas can wade around the Torre de la Higuera, a stone watchtower that tumbled into the ocean as a result of the earthquake in 1755.

But what of Lisbon, the sole European capital actually located on the continent's Atlantic coast, fully exposed to the earthquake's intensity?

The effects, there, were more devastating than one could ever imagine.

The effects, there, were more devastating than one could ever imagine.

According to contemporary testimony, the first tremors were so intense that entire buildings collapsed from the shaking. Within the capital's cathedral, massive stones began raining down on the faithful as the Gothic main chapel and the royal pantheon disintegrated.

Dozens who ran outside to escape the chaos were crushed when one tower collapsed (you can easily notice the part that fell away due to the different colored stones used in the reconstruction effort). Those who sought shelter in side chapels were buried alive in the rubble.

In the area now known as the Baixa, the sandy ground essentially liquified and swallowed up people and buildings. The labyrinthine roads of the medieval quarters became death traps, but even grand palaces weren't safe.

According to a chronicle from the era the much-loathed Spanish ambassador, Bernardo Antonio de Boixadors, VIII Count of Peralada, was found crushed to death under the massive, stone-carved coat of arms of Spain that fell off his palace's façade as he attempted to take flight.

The thousands upon thousands of candles lit in Lisbon's churches that morning, as well as the usual stove-fires lit in homes throughout the city, eventually led to a huge conflagration that posed a new threat to survivors after the initial tremors had passed.

Panicked residents ran to the Tereiro do Paço, the grand square next to the now partially ruined palace, in hopes of escaping the flames and falling masonry, and perhaps jumping aboard a ship headed to the other side of Tagus.

The decision was a fatal one: approximately 40 minutes after the earthquake, a tsunami hit Lisbon. Those in the square were smashed against the buildings and swept out into the Tagus, and further into the city, all those on low ground drowned.

Between the earthquake, the fire and the tsunami, Lisbon lost much of its cultural heritage.

The Casa da Índia, with its exhaustive archives of the Age of Discovery and detailed historical records of explorations by Vasco da Gama and other early navigators, was wiped out.

The Casa da Índia, with its exhaustive archives of the Age of Discovery and detailed historical records of explorations by Vasco da Gama and other early navigators, was wiped out.

The loss of the Paço da Ribeira was equally devastating: not only was it an architectural gem, but it also housed a 70,000-volume royal library and an extensive collection of artworks, including masterpieces by Titian, Rubens, and Correggio.

All gone.

All gone.

The Romanesque cathedral, which we mentioned before, was ruined. The brand new opera house: destroyed. Countless grand homes and palaces reduced to rubble.

And the human cost of the disaster was, of course, mind-boggling. Between 30,000 and 50,000 lives extinguished over the course of a single morning.

News of the disaster travelled fast and shocked the world. Enlightenment philosophers were especially disconcerted by the catastrophe: how could it be that God had chosen to punish Lisbon, considered by many to be the most faithful, Catholic city in the world?

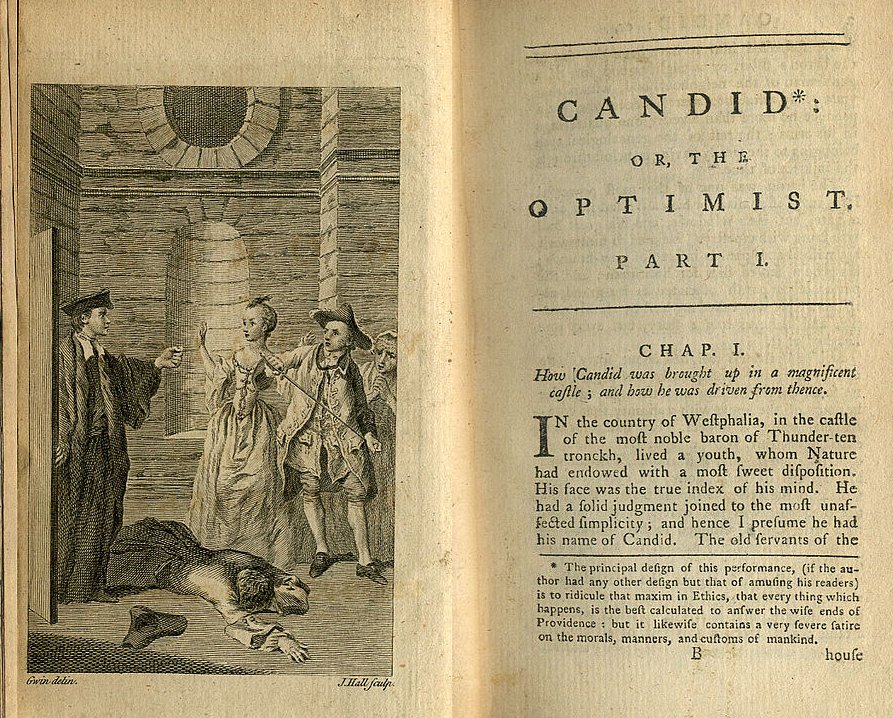

Voltaire famously used the disaster as proof that the philosophical optimism championed by Liebniz — essentially, the idea that we live in the best of all possible worlds — was idiotic.

In his satirical novel 'Candide' (1759), Voltaire sends his hero to Lisbon just as the earthquake strikes and uses the ensuing, indiscriminate suffering to highlight that there cannot possibly a God who intervenes to reward the virtuous and punish the guilty. Radical stuff.

More significant for us, however, is the impact that the event had on the wildly influential philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). His takeaway from the catastrophe was that modern cities were poorly constructed to deal with natural disasters like earthquakes.

Now, Rousseau being Rousseau, he took this thought to an extreme and used it to champion the idea that everyone should live in the countryside and return to nature (in line with his pastoral / noble savage fantasies). But the base idea — modern cities are not great — was not bad.

So here's where we get the earthquake's impact on urban planning, which requires us to point out that even though tens of thousands of people died in the disaster, the royal family was, miraculously, just fine.

On the morning of November 1, 1755, the Portuguese royal family headed out for a picnic in Belém, which today is a Lisbon suburb, but which at the time was decidedly outside the capital. Atop a hill, they saw everything collapse, go up in flames, and then get hit by giant waves.

The sight led the king, José I (1714-1777) to suffer a nervous breakdown and, I kid you not, refuse to live within any sort of solid building for the rest of his life. During the next three decades the Portuguese royal court existed within in a complex of tents and wooden shacks.

A few hours after the earthquake struck, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (1699-1782), a minor Portuguese noble who had somehow managed to survive the disaster in the city and make his way to Belém, presented himself before the disheveled monarch.

When the sobbing king wailed "whatever shall we do?" Carvalho e Melo gave a single-sentence response:

"We bury the dead and heal the living."

The confident answer was exactly what the king needed to give his full support to the noble. He was given control of, well, everything.

"We bury the dead and heal the living."

The confident answer was exactly what the king needed to give his full support to the noble. He was given control of, well, everything.

Carvalho e Melo — known to history as the Marquês de Pombal — declared martial law in Lisbon and had anyone caught looting summarily executed. Groups of men were pressed into service burying the dead and clearing rubble from the streets, and bread was distributed to survivors.

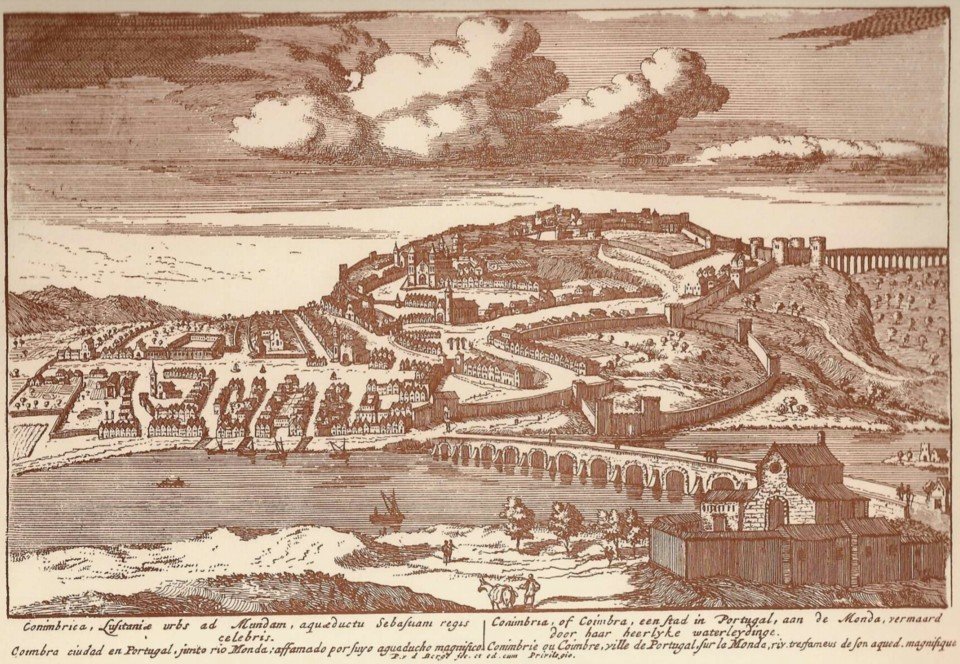

Rebuilding the city was, itself, an open question, as there was pressure to move the capital somewhere safer. Northern nobles pressed for the court to move to Porto, while others suggested Coimbra might be an ideal, central spot from which to govern Portugal.

Pombal, however, would not stand for such a thing, and was firm in his stance that Lisbon would remain the capital — but it would be rebuilt as a modern, rational city that embodied the spirit of the Enlightenment.

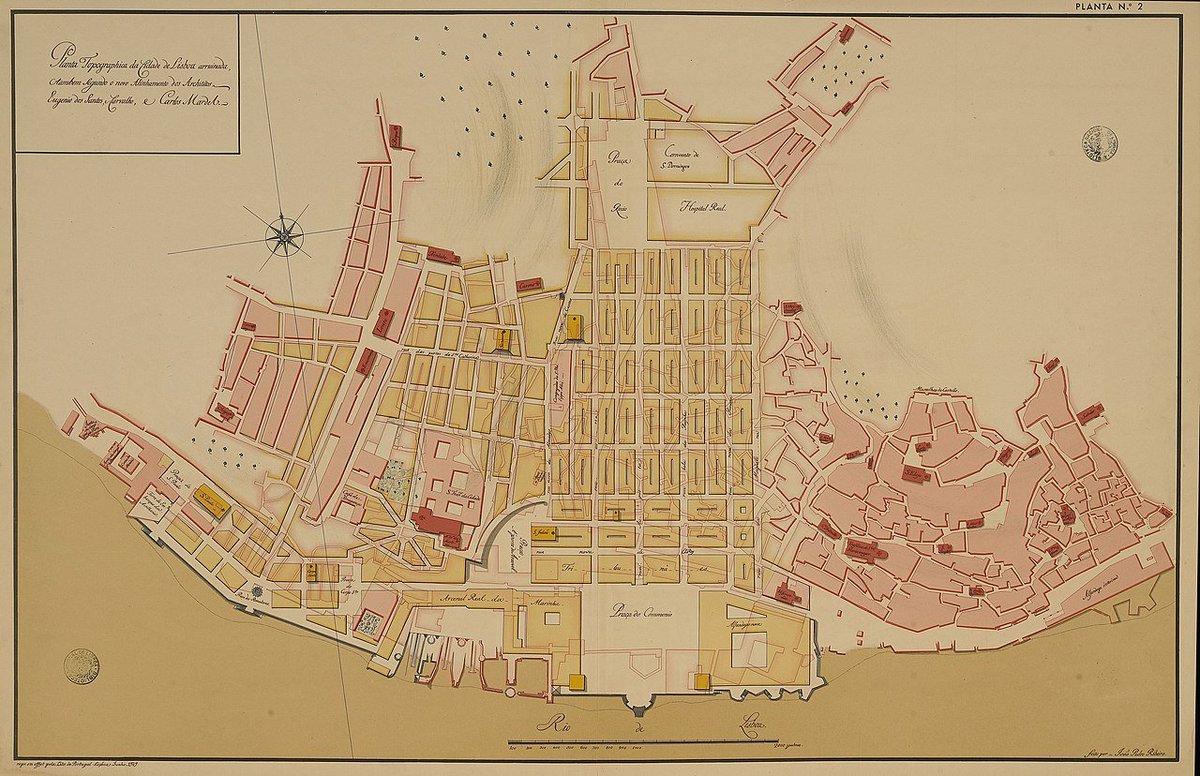

Pombal commissioned military engineers Eugénio dos Santos and Carlos Mardel to come up with a plan for the reconstruction of Lisbon, who set about redesigning the capital in rational grids, rather than the prior network of labyrinthine streets and alleys.

The perpendicular streets, organized around the central axis of the Rua Augusta, were carefully spaced for safety reasons: should an earthquake take place, one could stand in the center of the street and be distant enough from buildings to not be hit by falling masonry or rubble.

The buildings themselves were built on green pine piles driven into the sandy ground, and the ground floors featured vaulted brick ceilings topped by stone arches — all of this to secure the building against seismic tremors.

For the upper floors, the engineers developed the famed "gaiola pombalina" or Pomabline cage: a sort of interlocking wooden corset embedded in the walls to distribute seismic energy. And the windows were reinforced with stone frames for additional reinforcement.

I once read that before reconstruction began, Pombal had a model building built on the Tereiro do Paço and to test out its resistance to tremors he ordered most of the Portuguese army march around it for the better part of a day.

Dunno if that's true, but it's a great story.

Dunno if that's true, but it's a great story.

Whatever the testing methods, rebuilding got underway — much to the annoyance of the Portuguese aristocracy, that wanted to rebuild their Lisbon palaces exactly as they were prior to the earthquake. The nobility was also disconcerted by Pombal's social plan for the city...

...Because Pombal aimed to mix social classes in these buildings. The ground floor would be reserved for commercial uses, with shop owners living on the first floor. Nobles had the larger flats up top — but that meant they were also obliged to make trips up and down staircases.

There was a lot of pushback to this, but in the end exasperated nobles could either accept the new conditions or opt for payouts for their property. Many ended up leaving Lisbon and fixing their residences at what had formerly been country palaces outside the city.

Pombal's plan did not foresee the reconstruction of the Paço da Ribeira for various reasons. José I was refusing to live indoors, so there was no demand, and he had taken a liking to Ajuda hill, where he had set up his tent-court.

It should be noted that this was happening in an age when most European monarchs had decamped their capitals for larger residences where they were unlikely to be bothered by, say, furious mobs. Louis XIV had decamped to Versailles in 1682; Frederick the Great lived in Potsdam.

So given the Portuguese royal family wasn't going to need the space, Pombal turned the old site of the court into a spot celebrating the empire's commercial power. The perfectly symmetrical Praça do Comércio reinforced the idea of Portugal as a modern, enlightened maritime power.

Government offices were concentrated around the square which today continues to serve as the base of central power, with important ministries based in the buildings surrounding the square. At its center, Pombal placed a statute of José I sculpted by Joaquim Machado de Castro.

The statue was unveiled in 1775, which was also the date chosen to mark the formal inauguration of the square and, indeed, the reborn Portuguese capital. The reviews of the statue were not great: José I refused to pose for it, so its face looks nothing like him.

Although it was hailed for being the first successfully cast bronze equestrian statue in Portuguese history, locals jeered at the depiction of their disturbed king as a conquering hero, and even the royal family appeared to be embarrassed by the image.

The inaugural event came during the twilight of Pombal's power: two years later José I died and his successor, the equally disturbed and ultra-pious daughter, Maria I (1734-1816) came to the throne. The new queen detested Pombal and immediately put an end to his enlightened rule.

How much did Maria I hate Pombal? Allegedly, enough to decree that he had to stay at least 32 meters away from her at all times, and if she happened to pass by a house in which he was residing, he was obliged to leave it immediately if that distance was not observed.

Maria commissioned major building projects like the Basílica da Estrela and the Ajuda Palace, but she showed little interest for the works championed by Pombal. The Praça do Comércio was left unfinished and without the grand triumphal arch envisioned for it until the 1870's.

Appropriately, the arch now features a statue of the great urban planner who commissioned the square, who is depicted alongside other key figures from Portuguese history. He is also commemorated with a gargantuan statue in his eponymous square, further inland.

Wrapping up: 266 years ago Lisbon suffered an unspeakable tragedy that nearly put an end to its existence as a city, but it was fortunate enough to have a statesman come to power who was willing to take bold choices and redesign its landscape to ensure its survival.

In an age when we're likely to face catastrophes that aren't caused by seismic activity, but rather by climate change, we desperately need similarly bold leaders to take a long, hard look at our cities and enact strong, forward-thinking measures to ensure that we make it as well.

We don't need to wait for a disaster in order to shake up the way we lay out our streets, live in our buildings, organize our urban life: here's hoping for people will to take these steps ahead of what's to come.

Good afternoon.

Good afternoon.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh