This thread helps explain how Taylor Swift, Frank Ocean, and Christopher Nolan consistently generate great work:

They intuit a few principles for creating better writing, music, and art.

These principles also *eliminate the fear and procrastination preventing you from starting.*

The principles arise from first seeing yourself as a "craftsperson:"

These principles also *eliminate the fear and procrastination preventing you from starting.*

The principles arise from first seeing yourself as a "craftsperson:"

A craftsperson is someone who makes work the best it can be.

Counterintuitively, it’s not output that matters most to the craftsperson.

It’s honing a process that generates increasingly good output over time.

You cannot be a craftsperson unless the process is the reward.

Counterintuitively, it’s not output that matters most to the craftsperson.

It’s honing a process that generates increasingly good output over time.

You cannot be a craftsperson unless the process is the reward.

This philosophy also explains happiness:

Happiness isn't an end state. It’s having the freedom to pursue the continual grind you enjoy.

So, what is a process exactly?

It’s a craftsperson’s flow state wherein they exercise creativity, solve challenges, and chase perfection:

Happiness isn't an end state. It’s having the freedom to pursue the continual grind you enjoy.

So, what is a process exactly?

It’s a craftsperson’s flow state wherein they exercise creativity, solve challenges, and chase perfection:

We'll dive into that in a second.

Now for the second mindset shift: you cannot improve a process without exposing it to feedback.

From these two concepts, four principles emerge that guide us toward creating far better work going forward:

Now for the second mindset shift: you cannot improve a process without exposing it to feedback.

From these two concepts, four principles emerge that guide us toward creating far better work going forward:

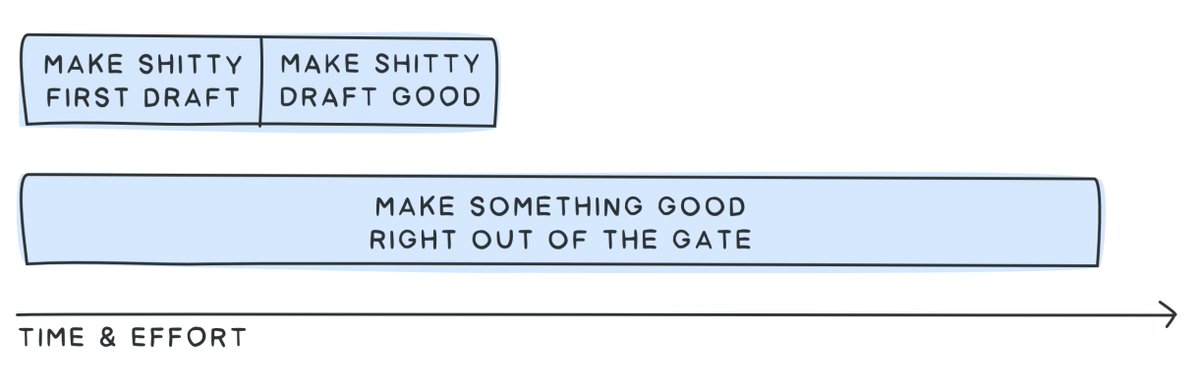

#1. Start with bad then iterate to great

Making something bad then iterating until it’s good is way faster than making something good upfront.

Making something bad then iterating until it’s good is way faster than making something good upfront.

When making something bad, our brains are good at reflexively seeing what’s wrong.

Is the song too high-pitched? Lower the pitch. Does the story have too many characters? Remove some.

Is the song too high-pitched? Lower the pitch. Does the story have too many characters? Remove some.

Instead, if we try creating something great upfront, which our brains aren’t good at, we have nothing to contrast against and iterate on—so we delusionally wait for great ideas to hit us.

This has a big implication on how craftspeople work:

This has a big implication on how craftspeople work:

When a craftsperson has a seed of an idea but is unsure where to start, they do not procrastinate by doing more research. They start by making something terrible.

They amuse themselves with how bad the initial work is, because they know that their starting work is not a reflection of the finished work’s quality.

It’s just a clearing of the mental pipe to let their brain begin contrasting.

Craftsperson Principle #2.

Narrow your scope:

It’s just a clearing of the mental pipe to let their brain begin contrasting.

Craftsperson Principle #2.

Narrow your scope:

To know which direction to head in, craftspeople narrow their scope:

Don’t write a movie, write a spy movie. Don’t write a song, write a love song.

Your brain freezes when facing too large of a scope. It doesn’t know which path to go down.

Don’t write a movie, write a spy movie. Don’t write a song, write a love song.

Your brain freezes when facing too large of a scope. It doesn’t know which path to go down.

The trick is to pursue whichever narrowed path excites you most.

Chase your enthusiasm down a rabbit hole—even if you're not sure it’s the best one.

You only need to start with something halfway good to later discover something great beyond it.

As my friend Joey put it:

Chase your enthusiasm down a rabbit hole—even if you're not sure it’s the best one.

You only need to start with something halfway good to later discover something great beyond it.

As my friend Joey put it:

"When I started producing music, I kept buying plugins thinking that would help me 'sound better.' And I would bounce from genre to genre. Now, I work in three genres and I use mostly default plugins that come with Ableton because they're great and the rest was procrastination."

Once you’ve done a good job with your constrained scope, that’s when you consider going bigger:

Expand scope one genre element at a time—nailing each before broadening further.

This is how good films are made. Behind every great blockbuster is a small, human story at its core.

Expand scope one genre element at a time—nailing each before broadening further.

This is how good films are made. Behind every great blockbuster is a small, human story at its core.

A delusion held by non-craftspeople is that they should wait “for inspiration to strike.”

No, you’re not supposed to wait for anything. That’s called procrastination.

No, you’re not supposed to wait for anything. That’s called procrastination.

Principle #3. Design a process

So what does a process actually look like?

It can be whatever works for you so long as it has one ingredient: confronting feedback.

Here's the short version of my own process.

First, I find resources where examples of my type of work exist:

So what does a process actually look like?

It can be whatever works for you so long as it has one ingredient: confronting feedback.

Here's the short version of my own process.

First, I find resources where examples of my type of work exist:

• If I’m making music, I’ll find the most-listened-to music by browsing Spotify charts.

• If I’m improving my public speaking, I’ll find the most charismatic conversationalists by filtering for the most-viewed celebrity interviews on YouTube.

• If I’m improving my public speaking, I’ll find the most charismatic conversationalists by filtering for the most-viewed celebrity interviews on YouTube.

In each case, I’m looking for a resource that lets me rank the best works and focus on those.

On Spotify, I can find the most-listened-to songs. These metrics may not be indicative of quality, but they’re certainly correlated. They’re a great place to start.

On Spotify, I can find the most-listened-to songs. These metrics may not be indicative of quality, but they’re certainly correlated. They’re a great place to start.

Then I build a list of the best works and the worst works.

My plan is to identify what the best ones have in common. To start, I want to imitate that.

Then I identify what the worst ones have in common. I want to avoid what makes them bad.

My plan is to identify what the best ones have in common. To start, I want to imitate that.

Then I identify what the worst ones have in common. I want to avoid what makes them bad.

Now, I create a work of my own:

I use as many of the good ingredients and as few of the bad ones as possible.

When in doubt, pursue what excites you. That's your north star.

Once you have a draft, ask people to rank your work against the best ones you found:

I use as many of the good ingredients and as few of the bad ones as possible.

When in doubt, pursue what excites you. That's your north star.

Once you have a draft, ask people to rank your work against the best ones you found:

Where does yours fall short? What ingredients can others identify from those works that you missed?

Rinse and repeat until you stop making significant improvements.

This is the process of deconstruction. It helps you master imitation, which is a wonderful starting point.

Why?

Rinse and repeat until you stop making significant improvements.

This is the process of deconstruction. It helps you master imitation, which is a wonderful starting point.

Why?

If you can reliably produce good work via imitation, it means you understand the mechanics of your craft.

Once you’ve achieved that, it’s easier to break free from those mechanics in pursuit of origination.

Origination is how you achieve *greatness.*

Let's dive in:

Once you’ve achieved that, it’s easier to break free from those mechanics in pursuit of origination.

Origination is how you achieve *greatness.*

Let's dive in:

4. In my opinion, greatness emerges from juxtaposition

When you reach the highest level of a craft, say playing guitar, it’s hard to identify the underlying ingredients.

Consider how every second of Jimmy Page’s guitar solos is a symphony of a hundred intuited decisions. Hmm...

When you reach the highest level of a craft, say playing guitar, it’s hard to identify the underlying ingredients.

Consider how every second of Jimmy Page’s guitar solos is a symphony of a hundred intuited decisions. Hmm...

You cannot capture all that on paper and memorize it as a framework.

Deconstruction fails us.

The solution?

Switch to high-volume experimentation.

This is a number’s game: try many things to allow for originality to spontaneously emerge.

What does an iteration look like?

Deconstruction fails us.

The solution?

Switch to high-volume experimentation.

This is a number’s game: try many things to allow for originality to spontaneously emerge.

What does an iteration look like?

Each iteration is a juxtaposition of ingredients:

You pair disparate ingredients from different works to see what emerges.

For example, if your craft is the guitar, you can mix solos from different genres.

If you’re writing novels, mix tropes from different genres...

You pair disparate ingredients from different works to see what emerges.

For example, if your craft is the guitar, you can mix solos from different genres.

If you’re writing novels, mix tropes from different genres...

If you’re producing music, mix samples from genres you’d never think could fit together.

Then, when an experiment produces a dopamine hit like you felt from a great work—you pause, analyze, and play.

Important note: The key concept in high-volume experimentation is “volume.”

Then, when an experiment produces a dopamine hit like you felt from a great work—you pause, analyze, and play.

Important note: The key concept in high-volume experimentation is “volume.”

The number of experimental iterations matters more than the number of hours spent experimenting.

Every time we receive feedback on an iteration, our eyes are opened to where we’re going wrong.

The “10,000 hours” rule is kinda misleading. It’s more like 10,000 iterations.

Every time we receive feedback on an iteration, our eyes are opened to where we’re going wrong.

The “10,000 hours” rule is kinda misleading. It’s more like 10,000 iterations.

When you factor in the need for both process and high-volume experimentation, you notice something:

A craftsperson’s process is 90% routine followed by 10% controlled chaos.

The sparks that occur between the two create the magic.

At least, that's my take ✌️

A craftsperson’s process is 90% routine followed by 10% controlled chaos.

The sparks that occur between the two create the magic.

At least, that's my take ✌️

Here’s the full version of this thread, including example videos add additional thoughts on overcoming procrastination:

julian.com/blog/craftspeo…

julian.com/blog/craftspeo…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh