Since one has to strike while the iron is hot, here is my attempt to summarize the Critique of Pure Reason by Kant (1781) in a series of tweets.

(I am not a Kant scholar and so it's gonna be wrong but that's no problem since Kant scholars can just take what I did & improve) 1/??

(I am not a Kant scholar and so it's gonna be wrong but that's no problem since Kant scholars can just take what I did & improve) 1/??

(preamble: this is meant for my non-philosophy audience since most philosophers know all of this probably better than I do as I shamefully only read CPR when I was in my early thirties. Sorry. I read the excellent Guyer & Wood translation which combines A and B edition. 2/

Ok so Kant (1724 – 1804) lived most of his life in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad in Russia).

He is known for the following key publications

Critique of Pure Reason (1781)

Critique of Practical Reason (1788)

Critique of Judgement (1790).

Now what does "critique" mean?

3/

He is known for the following key publications

Critique of Pure Reason (1781)

Critique of Practical Reason (1788)

Critique of Judgement (1790).

Now what does "critique" mean?

3/

Preface (Axii) of Critique of pure reason: "I do not mean by this a critique of books and systems, but of the faculty of reason in general, in respect of all knowledge after which it may strive independently of all experience" 4/

Ah the Enlightenment--as much about the limits of reason than of its scope, take that Pinker (subtweet). The text is long, difficult, and really hard for beginners. I do not recommend CPR for non-philosophers. Instead, read Prolegomena, Kant's own light version of it. 5/

Kant was a great thinker, with huge influence on philosophy. He wrote on all the major topics in philosophy, including metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, aesthetics, law, politics.

But alas not a brilliant writer (sorry I'm probably getting cancelled by Kant twitter now) 6/

But alas not a brilliant writer (sorry I'm probably getting cancelled by Kant twitter now) 6/

Kant went to university in Königsberg (the Albertina) at age 16, and left 6 years later. Was unable to secure a permanent academic position (a common problem then and now in the German-speaking world. First university post (private docent - Privatdozent) at age 31. Prof at 45 7/

He struggled with the problem: how do we combine knowledge obtained through senses with reason? (inaugural lecture as a professor). His answer to this problem was the Critique of Pure Reason (1781, 1787, CPR). 8/

The first edition is called the "A edition" (1781) the second "B edition" (1787). Kant scholars care a great deal about these and what's different between them but that's for when you really get into Kant. 9/

OK Preface. Kant lays the foundation for his critical theory. Prefaces introduce the problem of metaphysics. Why is metaphysics not making any progress? Our minds (reason) seem to ask questions all the time we can't answer e.g., whether you can know anything a prior 10/

In the B preface, Kant frames this problem in terms of Copernican revolution. Much like Copernicus shifted things by putting the Sun in the center, we need to realize that what we perceive depends on our cognitive capacities. Knowledge = not independent of our minds 11/

A preface says "Human reason has the peculiar fate ..that it is burdened with questions which it cannot dismiss, since they are given to it as problems by the nature of reason itself, but which it also cannot answer, since they transcend every capacity of human reason." 12/

But we can't help it, and so reason takes "refuge in principles that overstep all possible uses in experience … The battlefield of these endless controversies is called metaphysics” (A viii)

i.e., we try to make our reason do the impossible like answer whether God exists. 13/

i.e., we try to make our reason do the impossible like answer whether God exists. 13/

And we don't make progress. We have been asking whether God exists for AGES and we're not closer to finding a solution. The solution to this problem: instead of trying grand solutions and invoking things outside experience, philosophy must start over and examine reason itself 14/

That way, we can discover what reason is capable of knowing. Kant is optimistic: an accurate analysis of reason will guarantee a correct and complete system of metaphysics. Ta-da! Hence the project, Critique of Pure Reason. 15/

Oh dear I was being a bit enthusiastic. I've just only summarized (a bit of) the A and B Preface. Maybe to be continued tomorrow. (That's gonna be a looong thread). At least now you know, non-philosophers, why it's called Critique of Pure Reason /16 (for now)

In the Introduction, Kant makes two important distinctions:

* a priori and a posteriori cognitions

* analytic and synthetic judgments

What are these, and why does it matter, you ask? /17

* a priori and a posteriori cognitions

* analytic and synthetic judgments

What are these, and why does it matter, you ask? /17

Let's start with analytic statements:

Their truth value is determined by the meanings of their terms,

e.g. All squares are 4-sided

All bachelors are unmarried

Bc bachelor means unmarried man, you don't need to go out into the world and check each bachelor. You know a priori /18

Their truth value is determined by the meanings of their terms,

e.g. All squares are 4-sided

All bachelors are unmarried

Bc bachelor means unmarried man, you don't need to go out into the world and check each bachelor. You know a priori /18

By contrast, a synthetic statement is one where the truth value is NOT determined by the meaning of its terms, e.g.

The earth revolves around the sun.

To know whether this is true it's not sufficient to reflect on the meaning of the words "earth" and "sun" you need experience/19

The earth revolves around the sun.

To know whether this is true it's not sufficient to reflect on the meaning of the words "earth" and "sun" you need experience/19

So then we have 4 possible options (table 1)

Analytic Synthetic

A priori

A posteriori

Kant thinks analytic a priori's easy (e.g., a triangle has 3 sides). As is a posteriori synthetic (e.g., snow is white).

But what about the remaining options? /20

Analytic Synthetic

A priori

A posteriori

Kant thinks analytic a priori's easy (e.g., a triangle has 3 sides). As is a posteriori synthetic (e.g., snow is white).

But what about the remaining options? /20

Kant doesn't think there's such a thing as analytic a posteriori.

But what about synthetic a priori? Does it exist? Yes!

Kant believed math statements are synthetic a priori.

Even more controversially, he thought some statements in natural science are synthetic a priori /21

But what about synthetic a priori? Does it exist? Yes!

Kant believed math statements are synthetic a priori.

Even more controversially, he thought some statements in natural science are synthetic a priori /21

Now we get to the transcendental aesthetic, the part where Kant presents his first arguments that yes, synthetic a priori judgments do exist.

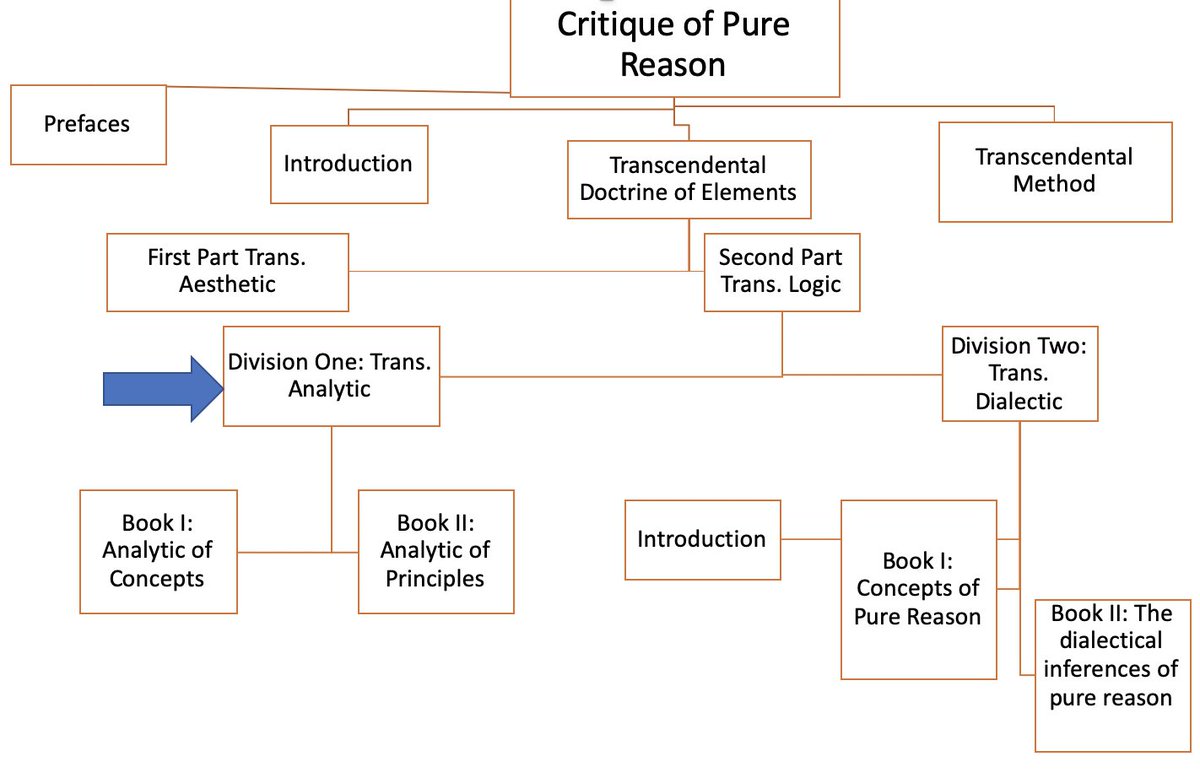

Btw we are here

Or this is an even better summary diagram by Andrew Stephenson /22 nebula.wsimg.com/f812ac8f2593c5…

Btw we are here

Or this is an even better summary diagram by Andrew Stephenson /22 nebula.wsimg.com/f812ac8f2593c5…

Here Kant argues that time and space aren't objective mind-independent features of reality. Rather, our cognition adds those things to our perception. This explains how it is possible to have knowledge that is both synthetic and a priori /23

We learn about the world through our senses (what Kant terms "sensibility"). When when you learn about an object (in Kantian terms, when object is given to one), you get an intuition. These intuitions are the raw materials our minds work with. /24

“So objects are given to us by means of sensibility, and that’s our only way of getting intuitions; but objects are thought through the understanding, which gives us concepts.” (A19/B33) /25

Kant’s argument: based on perceptions of spatial-temporal objects, our representations of space and time originate in a priori or pure forms of sensibility. The science of all principles of a priori sensibility is what he calls the ‘transcendental aesthetic’ (A21/B35) /26

He formulates several arguments for why we should think that time and space

* are prior to and not derived from experience

* but ALSO are within us and actively contributed by us to sensation and experience rather than passively received from the outer world /27

* are prior to and not derived from experience

* but ALSO are within us and actively contributed by us to sensation and experience rather than passively received from the outer world /27

Extremely summarizing these complicated arguments: The representation of space is of a singular, particular thing and, thus, is an intuition rather than a concept. Our representation of space is of an infinite and infinitely divisible whole

Analogous for time /28

Analogous for time /28

Here Kant disagrees with Newton who sees time and space as existing as an absolute "stage" independent from observers (Einstein would later undermine that picture). Nope, says Kant time and space depend on/are generated by our cognition /29

He also argues that accepting that space = synthetic a priori allows us to see how geometry is possible.

Geometrical statements such as "the shortest distance between two points is a straight line" are synthetic (not in definition) but also necessarily true, so a priori /30

Geometrical statements such as "the shortest distance between two points is a straight line" are synthetic (not in definition) but also necessarily true, so a priori /30

Aha but non-Euclidean geometry you might say triumphantly. Well, not a problem for Kant since he thinks geometry is a product of our cognition. He's not a realist about space anyway. All that is needed for this argument to work is that our intuitive geometry = euclidean /31

(I might continue this later--didn't quite realize what I was getting myself into. Anyway this song here is a great summary of the Critique of Pure Reason that is even shorter!)

/32

/32

So, space & time are not things in themselves but formal features of how we perceive objects. Objects in space and time are “appearances”. Kants think we know nothing of substance about the things in themselves of which they are appearances. /33

He calls this doctrine "transcendental idealism”

Both in CPR and Prolegomena (1783) Kant distinguishes his transcendental idealism from other kinds of idealism: * problematic idealism (he attributes to Descartes)

* dogmatic idealism (attributed to Berkeley). /34

Both in CPR and Prolegomena (1783) Kant distinguishes his transcendental idealism from other kinds of idealism: * problematic idealism (he attributes to Descartes)

* dogmatic idealism (attributed to Berkeley). /34

Problematic idealism assumes "we can’t prove the existence of anything except ourselves" (B275). However, Descartes is wrong because we actually have experiences: "we have experience of outer things, rather than merely imagining them" (B275)

Descartes refuted /35

Descartes refuted /35

Kant's idealism was also compared to Berkeley, notably in Garve-Feder's review of the Critique in 1782. He got so angry that he crytyped the Prolegomena (I am so, so misunderstood!) Unlike Berkeley, Kant DOES affirm there are mind-independent objects "things in themselves” /36

The objects affect us but we can't experience them as they are. So when you see a table there's something independent of your mind that leads you to think and see "table" but you can never see the table as it truly/mind-independently (whatever that is) is /37

“I understand by the transcendental idealism of all appearances the doctrine that they are all together to be regarded as mere representations and not as things in themselves, and accordingly that space and time are only sensible forms of our intuition” (A369) /38

[side note: It now seems pretty obvious to us that our brain and senses structure how we see the world. But in Kant's time this was not at all obvious. Also, there are other philosophical traditions reaching similar conclusions e.g., Yogācāra, a Buddhist school of thought] /39

After the Transcendental Aesthetic, we move on to the Transcendental Logic. We are here, at the first part of the Transcendental Logic, termed the Transcendental Analytic. /40

The transcendental Analytic aims to defend legitimate uses of a priori concepts (which Kant calls "the categories"). These will help us to attain metaphysical knowledge (the question he set out in the preface: How can we get metaphysical knowledge and not get stuck? /41

Kant says there are faculties are involved in experience: sensibility and understanding:

* sensibility: organs & functions of sensation

- a priori elements (not based on experience): space & time

- a posteriori (based on experience): sensations that give rise to intuitions /42

* sensibility: organs & functions of sensation

- a priori elements (not based on experience): space & time

- a posteriori (based on experience): sensations that give rise to intuitions /42

Remember that "intuitions" for Kant is not how we use intuitions--they are rather deliverances of our senses, to put it in a imprecise analogy, you might see an object that looks brown, rectangular but your mind needs to interpret is as a table. So we need something else ... 43/

And that's the understanding.

The understanding is the faculty (ability, power) concerned with actively producing knowledge by means of concepts. Without the understanding you would just have meaningless stuff you see, smell etc but not be able to make any judgments 44/

The understanding is the faculty (ability, power) concerned with actively producing knowledge by means of concepts. Without the understanding you would just have meaningless stuff you see, smell etc but not be able to make any judgments 44/

For Kant, having an experience is one of the following:

* forming a belief

* committing yourself to the truth of a proposition

* to make a knowledge claim

A birdwatcher sees a bird and thinks "I see a common loon". She's committing herself to the truth of that proposition. 45/

* forming a belief

* committing yourself to the truth of a proposition

* to make a knowledge claim

A birdwatcher sees a bird and thinks "I see a common loon". She's committing herself to the truth of that proposition. 45/

According to Kant, if it were not the case that perception involves judgment, experience wouldn’t be capable of delivering knowledge about the empirical world.

So how do we get knowledge of the empirical world?

(recall Kant thinks our minds always structure this)

46/

So how do we get knowledge of the empirical world?

(recall Kant thinks our minds always structure this)

46/

Kant established in the Transcendental Aesthetic that space and time are not features of an objective, mind-independent reality.

Now he's saying neither are substance and cause

The empirical world, the world of experience is a world of causally interacting substances. 47/

Now he's saying neither are substance and cause

The empirical world, the world of experience is a world of causally interacting substances. 47/

We perceive the empirical world as such as a result of the workings of understanding. It may seem weird to think that concepts structure our perception, but research on e.g., colors bears this out. Strawberries appear red even though no red in pixels 48/

https://twitter.com/Foervraengd/status/1289599209113436161

So this part of the CPR is concerned with: where do our ideas come from? a venerable philosophical question.

Locke (empiricism) argued that all our ideas ultimately come from experience, whereas Descartes (rationalism) thought they come from reason. Kant thinks neither works 50/

Locke (empiricism) argued that all our ideas ultimately come from experience, whereas Descartes (rationalism) thought they come from reason. Kant thinks neither works 50/

Here he brings in the idea of the categories.

What are categories (for Kant)?

a collection of basic concepts without which experience would not be possible

they are a priori – presupposed, not derived from experience

whenever we make a judgement we employ categories 51/

What are categories (for Kant)?

a collection of basic concepts without which experience would not be possible

they are a priori – presupposed, not derived from experience

whenever we make a judgement we employ categories 51/

We then get a “guiding-thread” to the “discovery of all pure concepts of the understanding” (A-edition), or the “metaphysical deduction of the categories” (B-edition). 52/

Kant aims two things:

(1) identify the categories exhaustively, in a principled way

(2) show that they are pure concepts, originating in the understanding. I.e., there is no sense perception involved in the forming of the categories 53/

(1) identify the categories exhaustively, in a principled way

(2) show that they are pure concepts, originating in the understanding. I.e., there is no sense perception involved in the forming of the categories 53/

The term "category” in philosophy is quite narrow.

Suppose you were to speak about everything, how would you do it? You'd use fundamental categories to try to divvy things up.

Only those fundamental categories are called categories in philosophy 54/

Suppose you were to speak about everything, how would you do it? You'd use fundamental categories to try to divvy things up.

Only those fundamental categories are called categories in philosophy 54/

Philosophers did try to make a comprehensive list of all the categories. For example, Aristotle postulated at least 10 categories: substance, quantity, qualification, relative, where, when, being- in-a-position, having, doing, being-affected. But Kant was not impressed 55/

“Aristotle’s search for these fundamental concepts was an effort worthy of an acute man. But since he had no principle, he rounded them up as he stumbled on them, and first got up a list of ten of them, which he called categories... But his table still had holes” (A81/B107)

So here's Kant take of all the categories, ever

Quantity: Singular, Particular, Universal

Quality: Affirmative, Negative, Infinite

Relation: Categorical, Hypothetical, Disjunctive

Modality: Problematic, Assertoric, Apodictic 57/

Quantity: Singular, Particular, Universal

Quality: Affirmative, Negative, Infinite

Relation: Categorical, Hypothetical, Disjunctive

Modality: Problematic, Assertoric, Apodictic 57/

Too much to go into why he chooses there but crudely and briefly, he's focusing on relations of a particular form while abstracting from particular content (bc the categories are purely intellectual, no empirical basis) 58/

Each and every judgement will posses one feature from each of these groups

For example: “Nicola Sturgeon is from Scotland or England” is singular, affirmative, disjunctive and assertoric.

And so you have judgments about empirical things that are structured by categories 59/

For example: “Nicola Sturgeon is from Scotland or England” is singular, affirmative, disjunctive and assertoric.

And so you have judgments about empirical things that are structured by categories 59/

I'm not really sure to continue this with the Transcendental Deduction of the Categories tomorrow, one of the most difficult parts of the CPR. It baffled readers in 1781. The elucidations in B editions didn't really help. I find it baffling. 60/

Huge scholarly debate and difficulty of the Transcendental Deduction of the Categories (TDC henceforth), but will do my best. Aim of TDC is to establish the objective validity of the categories 61/

Before proceeding we need to know what a transcendental argument (TA) is. A TA takes a compelling premise about our thought, experience, or knowledge, and then reasons to a conclusion that is a substantive and unobvious presupposition and necessary condition of this premise 62/

* there's a feature F about our experience/thought/cognition

* If you accept that F is indeed a feature of our experience/thought/cognition, then you necessarily require a substantive condition C to explain it

* Thus, C is true 63/

* If you accept that F is indeed a feature of our experience/thought/cognition, then you necessarily require a substantive condition C to explain it

* Thus, C is true 63/

Also, “deduction” is not strictly used in the sense of deductive reasoning

Rather, this terminology hails from German legal vocabulary: Deduktion signifies an argument intended to yield a historical justification for the legitimacy of a property claim 64/

Rather, this terminology hails from German legal vocabulary: Deduktion signifies an argument intended to yield a historical justification for the legitimacy of a property claim 64/

"among the many concepts that make up the very complicated web of human cognition there are some that are determined for pure a priori employment (completely independent of all experience), and these always require a deduction of their authority..." (A85/B117) 65/

So the TDC aims to show that there are a priori concepts that apply to objects, and that our a priori knowledge of these objects is more than our mere representations of them. Think of e.g., causality. Hume thought we don't really know causes. 66/

All we can see is "if x happens, y tends to happen" but we don't quite see the actual *cause*, you just observe a "constant conjunction" of presumed cause and presumed effect. But according to Kant, you can know intellectual principles, a priori and synthetically 67/

Until 1781, Kant had no clear strategy to prove the principle of causality and the other intellectual principles. He struggled with them in his inaugural dissertation in 1770, calling them “principles of convenience” (akin to Hume’s skeptical use of them) 68/

In the A-edition (1781) he used the following strategy: use the categories as the link between the idea of making any judgements about objects and the intellectual principles of causation and conservation (which he had always wanted to prove) 69/

Categories are the concepts by means of which we organize our intuitions in order to make them accessible to judgements. This transcendental content is added to manifold of intuitions. Recall Kant had 12 categories and his justification of this is not impressive 70/

Problems with the categories e.g., what's the relation between them? What is the difference between reality (under Quality) and existence (under Modality)?

Kant sometimes shortens this number to 6, 5 or even 3 (his diatribe against Aristotle boomerangs) 71/

Kant sometimes shortens this number to 6, 5 or even 3 (his diatribe against Aristotle boomerangs) 71/

Here follows an imperfect, incomplete and short summary of the Transcendental Deduction of the Categories 1.0 from the A edition (1781) -- sorry, Kant scholars 72/

We need to explain how we can have knowledge of objects. What is required?

* self-consciousness, which Kant calls "transcendental apperception” (where world and mind come together)

* synthesis (sensibility + understanding) 73/

* self-consciousness, which Kant calls "transcendental apperception” (where world and mind come together)

* synthesis (sensibility + understanding) 73/

If I have a representation it must be possible for me to be conscious of my having it. As Kant puts it, “it must be possible for the ‘I think’ to accompany all my representations” (B131/132)

Now, asks Kant, how is such self-consciousness possible? 74/

Now, asks Kant, how is such self-consciousness possible? 74/

I don’t intuit myself

I have an intellectual awareness of myself through an awareness that my synthesized representations are the product of an act of synthesis

but if I am to be self-conscious in this way, then I must synthecize my intuitions

This requires the categories 75/

I have an intellectual awareness of myself through an awareness that my synthesized representations are the product of an act of synthesis

but if I am to be self-conscious in this way, then I must synthecize my intuitions

This requires the categories 75/

For only because I ascribe all perceptions to one consciousness...can I say of all perceptions that I am conscious of them. There must therefore be an objective ground...on which rests the possibility indeed even the necessity of a law extending through all appearances (A120)76/

So,1.all representations belong to a single self

2.this is a synthetic connection of representations, which

3.requires an a priori synthesis among them

4.the rules of which are the categories, which are

5.necessary conditions for the representation of any objects by the self 77/

2.this is a synthetic connection of representations, which

3.requires an a priori synthesis among them

4.the rules of which are the categories, which are

5.necessary conditions for the representation of any objects by the self 77/

Unfortunately, critics of Kant pointed out that Kant has failed to establish a firm connection between unity of apperception and categories. He didn't show that transcendental unity of apperception requires knowledge of objects distinct from the self. 78/

He tried to fix the TDC in the Prolegomena (TDC 1.1) but that didn't work either. So on to Kant's third try: Transcendental Deduction of the Categories 2.0, B edition 79/

Hmmm this seems unsummarizable in tweets Let's try anyway. Kant follows Hume’s idea that consciousness appears disunified (by contrast, Descartes thought you have a unified "I"). Yet, there's a connection of all possible representations to a single self 80/

Kant then asserts, as in the A edition, that we have genuine a priori knowledge of the necessary connection of all representations to this single self, and that there must therefore be an a priori synthesis of the understanding. In A edition, he then goes on to categories 81/

But now he goes into this super-convoluted detour where he identifies the unity of apperception with cognition of objects.

Nice try, didn't quite work. Yet the underlying idea that our mind guides the experience we have of the world is still accepted today 82/

Nice try, didn't quite work. Yet the underlying idea that our mind guides the experience we have of the world is still accepted today 82/

OK so wow. I was hoping to do this in under 100 tweets. Just for reference, we're here now. For reference what this looks like in the Guyer & Wood translation, we're here--a bit under halfway! 83/

We've done the transcendental aesthetic (about sensibility). Now we're in the transcendental analytic (about the understanding). We've looked at the categories w the metaphysical deduction and transcendental deduction of the categories.

Now we're in the analytic of principles 84/

Now we're in the analytic of principles 84/

To summarize

sensibility = passive, receptive. Intuitions about space and time.

understanding = faculty that actively structures what we sense how? by applying concepts to sensory experience (through the categories, high-level concepts that provide a template) 85/

sensibility = passive, receptive. Intuitions about space and time.

understanding = faculty that actively structures what we sense how? by applying concepts to sensory experience (through the categories, high-level concepts that provide a template) 85/

A judgment is roughly a thought, which involves a synthesis of sensibility and understanding.

"The car got damaged by crashing into a tree". Now how do we make this judgment? Not enough to just have sensory input (Hume thought that's all we use to make a causal judgment) 86/

"The car got damaged by crashing into a tree". Now how do we make this judgment? Not enough to just have sensory input (Hume thought that's all we use to make a causal judgment) 86/

But how do we make such a judgment? As an empiricist, Hume wanted to ground everything in perception – impressions, constant conjunction of cars and trees

so for Hume, causation is not a real, objective feature of our experience, we infer it. 87/

so for Hume, causation is not a real, objective feature of our experience, we infer it. 87/

To make judgments, we don’t have enough with sensibility (here Kant is against Hume&other empiricists). If you're an empiricist how can you believe in e.g., the existence of the street when you go indoors? The cognitive power of judgement must have transcendental structure 88/

Skepticism since ancient Greek philosophy denies that we can know anything with certainty about reality, in particular about substance, cause, and the external world. Kant argues against skeptics: we *can* know something about reality 89/

Our cognition has regulative principles help to turn mere intuitions into perceptions of objects in space and time.

We then have

* Analogies of experience: principles of substance and causal connection are necessary to locate objects objectively in time 90/

We then have

* Analogies of experience: principles of substance and causal connection are necessary to locate objects objectively in time 90/

* Postulates of empirical thought: we can judge the possibility, actuality and necessity of states of affairs thanks to these principles /91

Kant also added Refutation of Idealism to the B edition.

This argument rejects Berkeley’s view that knowledge of material objects is impossible, responds to Descartes’ view that self-knowledge is more certain than knowledge of external objects. /92

This argument rejects Berkeley’s view that knowledge of material objects is impossible, responds to Descartes’ view that self-knowledge is more certain than knowledge of external objects. /92

Then we come to a really cool and neat part of CPR, the transcendental dialectic, second part of the transcendental logic (you are here...) 93/

Recall in the Preface Kant remarks how we're asking our minds to solve all sorts of impossible questions, questions that go beyond what it can solve such as "Do we have a soul" and "is there a God?"

Our demand for these ultimate explanations is a byproduct of our reasoning 94/

Our demand for these ultimate explanations is a byproduct of our reasoning 94/

And is thus inevitable. But it gives rise to a specific error, the transcendental illusion

this is to “take a subjective necessity of a connection of our concepts … for an objective necessity in the determination of things in themselves” (A297/B354). 95/

this is to “take a subjective necessity of a connection of our concepts … for an objective necessity in the determination of things in themselves” (A297/B354). 95/

Differently put: There are limits to our knowledge.

We tend to overstep these limitations (by using principles, e.g., causality, outside of the world of experience. You can't for Kant infer a "first cause" of the universe i.e., God as some natural theological arguments do). 96/

We tend to overstep these limitations (by using principles, e.g., causality, outside of the world of experience. You can't for Kant infer a "first cause" of the universe i.e., God as some natural theological arguments do). 96/

This is not an easily avoidable error of reasoning! Simply thinking more deeply won’t solve it.

Rather, the illusion is a result of the way our reasoning is structured.

Here Kant prefigures biases literature in cognitive science. 97/

Rather, the illusion is a result of the way our reasoning is structured.

Here Kant prefigures biases literature in cognitive science. 97/

Just to pick out one interesting argument in this section: Why Kant believes the ontological argument doesn't work. Ontological arguments tend to infer God's existence from a definition (e.g., greatest possible being that can be imagined in Anselm's argument 98/

Central to his main objection against ontological argument: existence is not a predicate.

Ontological arguments say: existing is better than not existing. This assumes that existence is a predicate e.g., "this apple is red" is equivalent to "this apple exists" but it isn't. 99/

Ontological arguments say: existing is better than not existing. This assumes that existence is a predicate e.g., "this apple is red" is equivalent to "this apple exists" but it isn't. 99/

“God does not exist” is not to deny that God has some specific property.

Rather, it’s saying that the concept of God does not apply to anything, i.e., nothing falls under the concept God. And you can totally do that. Hence, ontological argument doesn't work /100

Rather, it’s saying that the concept of God does not apply to anything, i.e., nothing falls under the concept God. And you can totally do that. Hence, ontological argument doesn't work /100

Anyway, it's been fun. I was going to keep this at 100 tweets. You now have a short overview (not complete, but with many of the important bits) of Critique of Pure Reason. If you think this is long, I invite you to read the book! /end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh