17 Nov: Exploring exploratory analyses

For Lung Cancer Awareness Month #LCAM I’m going to summarize 30 important lung cancer trials over 30 days. These posts are directed at non-medical professionals, with descriptions of the results and of what makes a good trial. #lcsm 1/14

For Lung Cancer Awareness Month #LCAM I’m going to summarize 30 important lung cancer trials over 30 days. These posts are directed at non-medical professionals, with descriptions of the results and of what makes a good trial. #lcsm 1/14

We have previously looked at adjuvant chemotherapy (Nov 2) and osimertinib (14 November). Today we’ll look at another influential adjuvant study, and ask whether it ought to be as influential as it is. 2/14

This trial enrolled people exclusively who had had stage Ib cancers removed surgically. In the staging system in use at the time, stage Ib was any tumour larger than 3 cm, with no lymph nodes involved (today many of these would be given a higher stage). 3/14

This trial randomized people to either chemotherapy with carboplatin/paclitaxel or to observation. The primary outcome was overall survival, and the trial was designed with a power of 80% to detect an improvement in 5 year OS from 50% to 63% (see 12 Nov) 4/14

The trial ran into a series of troubles. Accrual was very slow, requiring reduction in the sample size and corresponding adjustments in the statistical plan. Then the trial was stopped at an interim analysis due to a survival signal that disappeared with longer follow up. 5/14

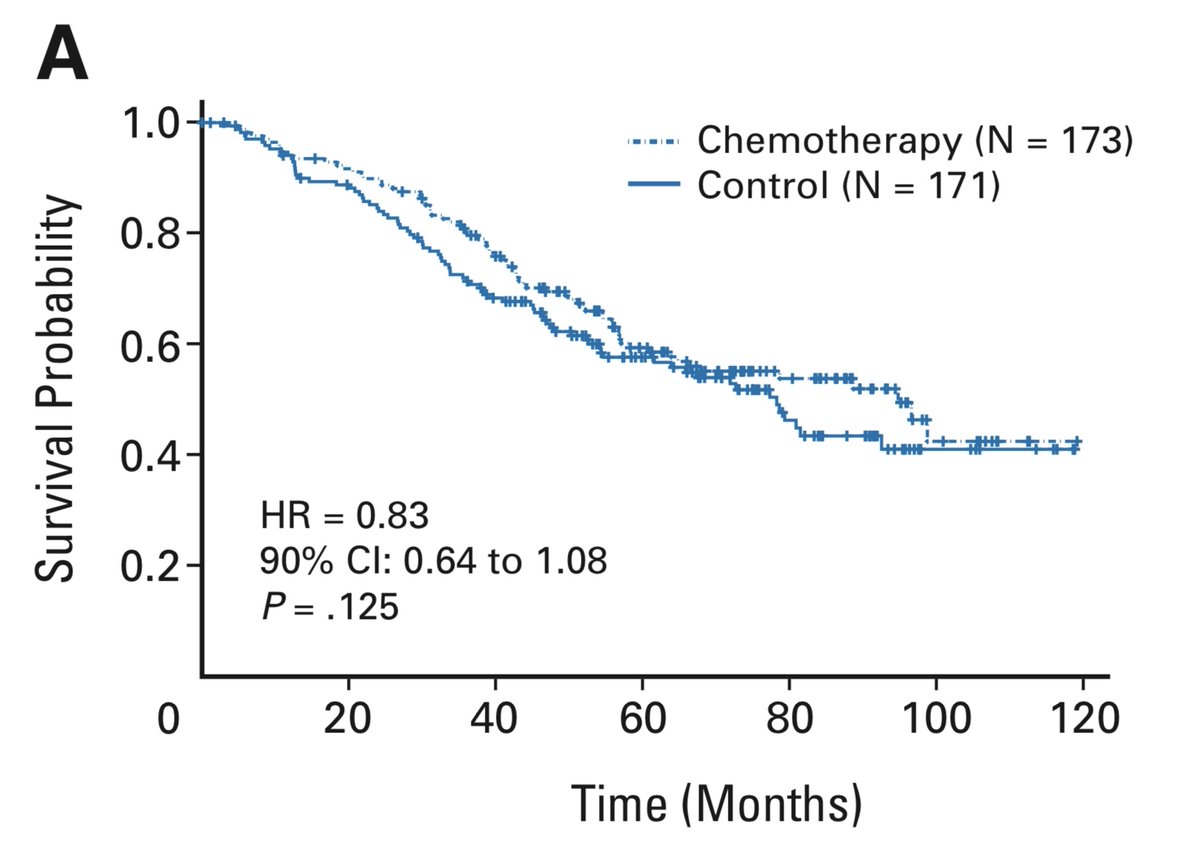

In the end, the trial was negative. There was no evidence that adjuvant carboplatin/paclitaxel increased survival for people with this stage of disease. This was in contrast to other adjuvant trials reporting results around the same time. 6/14

Possible reasons for this trial being negative when others are positive include:

1. This trial was too small (underpowered)

2. Less (or no) benefit for node-negative tumours

3. This trial used carboplatin while others used cisplatin

7/14

1. This trial was too small (underpowered)

2. Less (or no) benefit for node-negative tumours

3. This trial used carboplatin while others used cisplatin

7/14

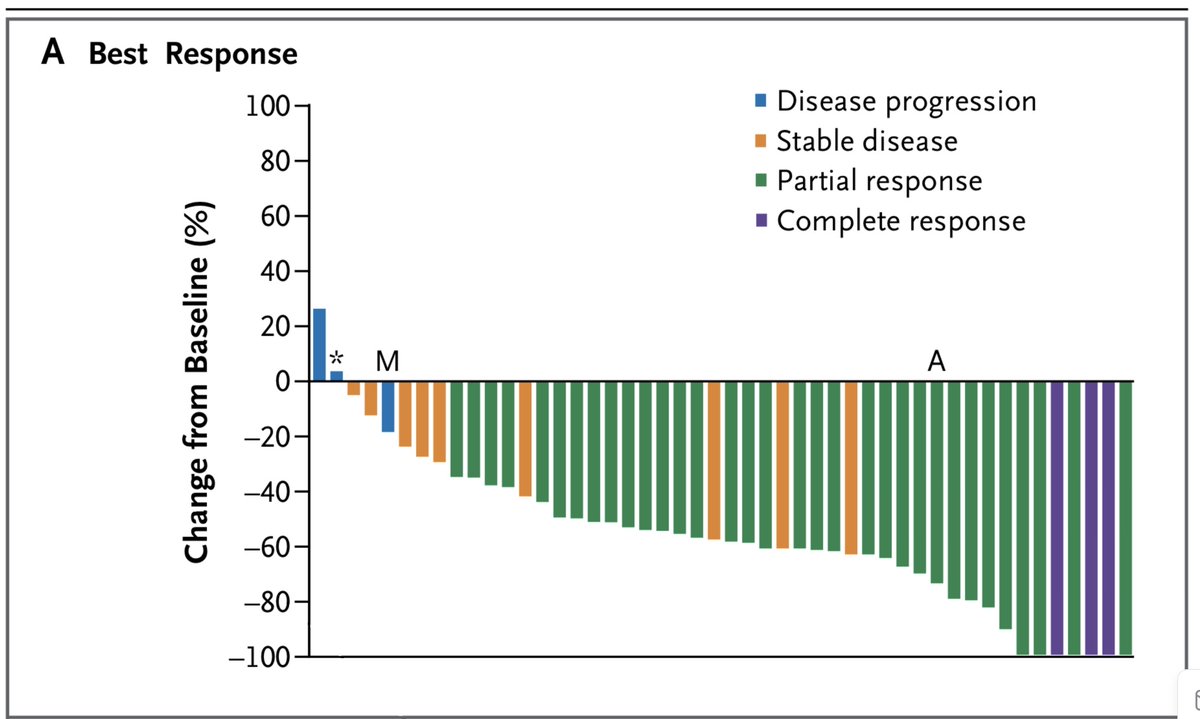

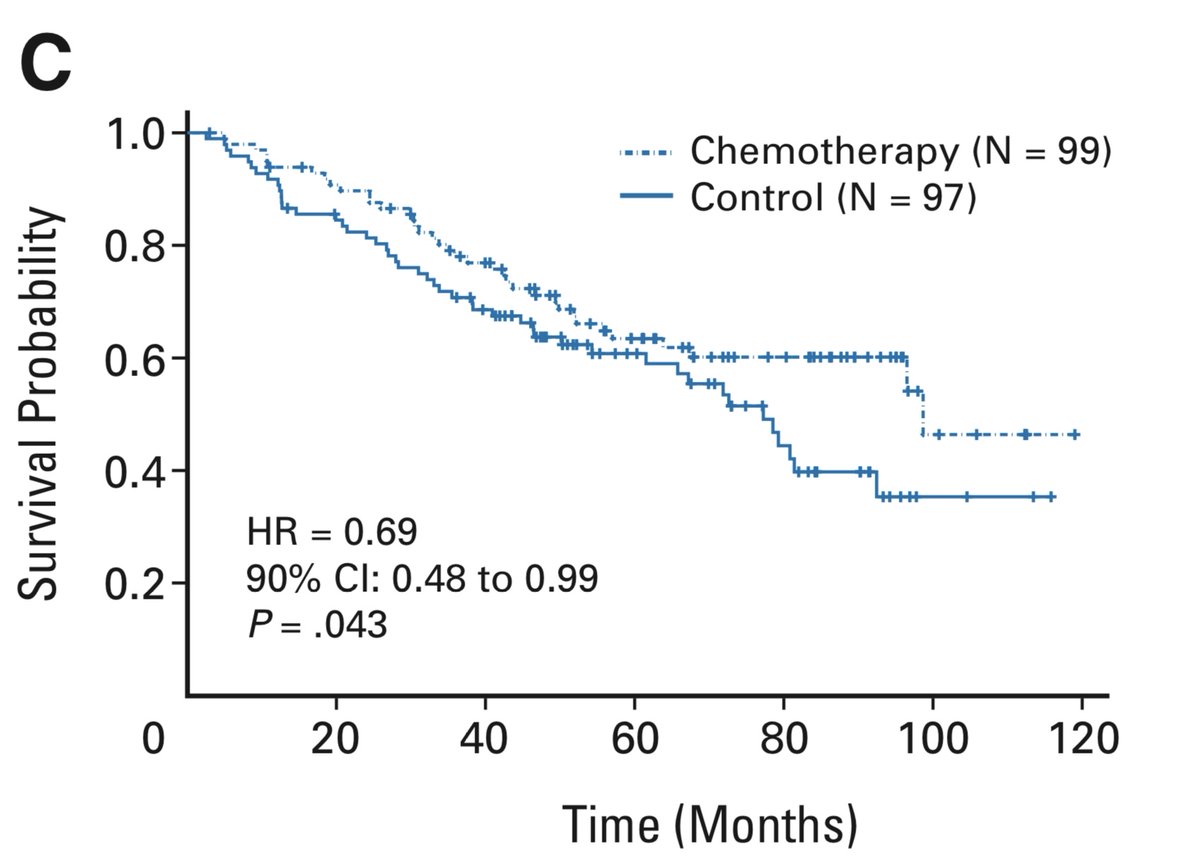

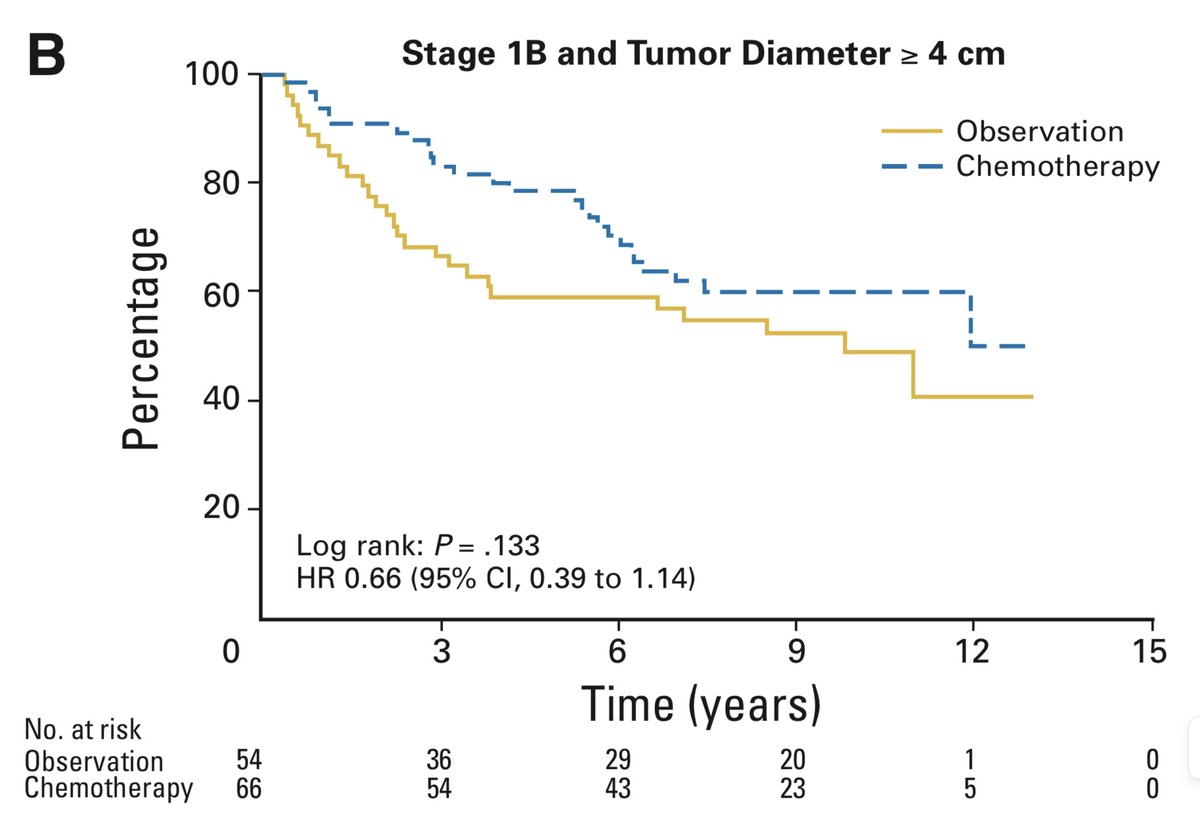

Though the authors are frank in their assessment that the trial is negative, they go on to present an “Exploratory Analysis” looking at the subgroup whose tumours were larger than 4 cm. This is different from subgroup analysis, in that it was not pre-specified during study design

A major problem with such analyses is that statistics can’t tell us the risk of an outcome being due to chance. If I presented 40 subgroup analyses and one was positive, you’d be skeptical. If I did 40 exploratory analyses and published only the positive one, how would you know?

The exploratory analysis suggested benefit to chemo in this >4 cm subgroup, albeit only significant due to the statistical expedient of a one-sided test (more on this another day). 10/14

This is a very shaky basis on which to suggest chemotherapy to a group of people, many of whom are already cured by surgery. Some further strength was given to this position, however, when the Canadian adjuvant trial (see 2 Nov) did a similar analysis and got a similar result.

I feel no hesitation recommending adjuvant chemo to those with resected node-positive lung cancers. While most guidelines also recommend chemo for node-negative tumours over 4 cm, we should recognize that this recommendation is based on weaker evidence. 12/14

The strength of the recommendation comes out in the discussion of treatment options with the patient. A treatment decision reflects a balance of patient preference and judgement, along with a doctor’s advice. When the advice is less strong, patient preference plays a bigger role

Tomorrow we’ll talk about another chemo trial, and make some comments about placebos and blinding.

14/14

14/14

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh