🆕 #archaeology: Ancient Egyptian reliefs in Thebes provide a snapshot of how the ancient artists worked with traces of on-the-job training, apprentices making mistakes, masters showing off, and more.

Here's an #AntiquityThread on the find 1/n 🧵

🔗 (🆓) buff.ly/3oubehA

Here's an #AntiquityThread on the find 1/n 🧵

🔗 (🆓) buff.ly/3oubehA

The discovery was made at the Temple of Hatshepsut in Thebes, dedicated to the female pharaoh of the same name who ruled from 1473 – 1458 BC. 2/

📷: The Temple of Hatshepsut by Maciej Jawornicki

📷: The Temple of Hatshepsut by Maciej Jawornicki

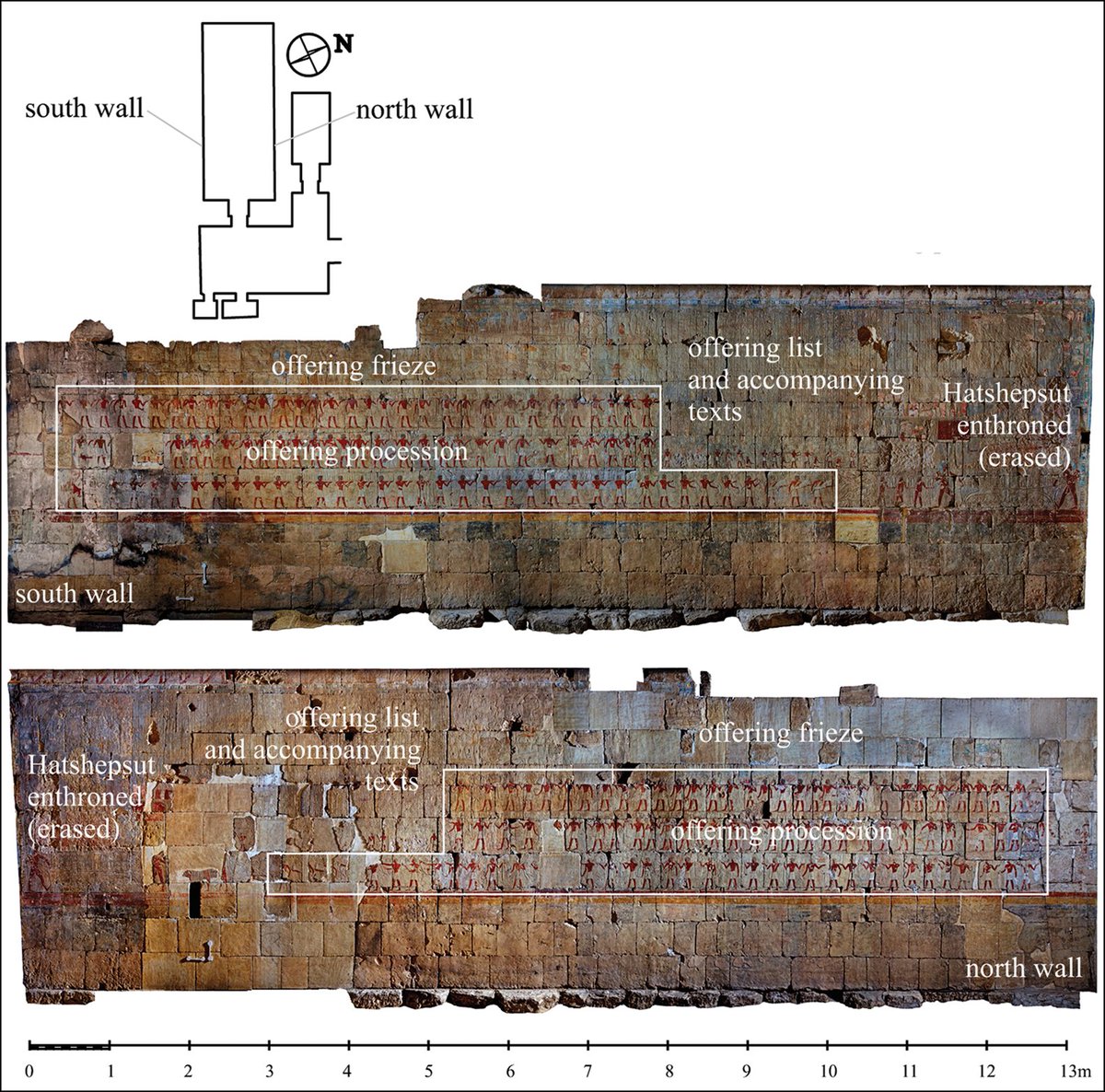

In the largest room of the temple, known as the Chapel of Hatshepsut, are mirrored reliefs of a procession bringing offerings to the pharaoh. 3/

📷: The reliefs

📷: The reliefs

For nearly a decade, researchers worked to fully document these massive reliefs; each of which is nearly 13 metres long and features 100 figures of offering bearers, along with the enthroned Hatshepsut and the list of her offering menu. 4/

📷: Part of the documentation process

📷: Part of the documentation process

In the process of documentation, Dr Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska, from @PCMA_UW, discovered traces of most of the steps of the relief making process in the art. 5/

📷: Dr Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska at work

📷: Dr Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska at work

“I couldn’t stop thinking our documentation team was replicating the actions of those who created these images 3,500 years ago. Like us, ancient sculptors sat on scaffolding, chatting and working together,” said said Dr Stupko-Lubczynska 6/

Archaeologists had long known how ancient Egyptian art was made thanks to half-finished pieces preserving the process in action. However, as each step in production covered up the previous one, evidence from finished pieces is rare. 7/

📷: Half finished art

📷: Half finished art

The process, with traces of most seen in the Chapel, is:

1️⃣ Smoothing the wall.

2️⃣ Adding a guide grid.

3️⃣ A preliminary sketch.

4️⃣ A master artist makes corrections.

5️⃣ Adding text.

6️⃣ Sculpting.

7️⃣ Whitewash and colouring.

8/

📷: Guide grid traces at the Chapel

1️⃣ Smoothing the wall.

2️⃣ Adding a guide grid.

3️⃣ A preliminary sketch.

4️⃣ A master artist makes corrections.

5️⃣ Adding text.

6️⃣ Sculpting.

7️⃣ Whitewash and colouring.

8/

📷: Guide grid traces at the Chapel

However, as well as studying how the art was made, Dr Stupko-Lubczynska also wanted to explore who was behind it:

“By studying traces left in the stone by ancient chisels, it was possible to ‘grasp’ several intangible phenomena, which normally leave no evidence." 9/

“By studying traces left in the stone by ancient chisels, it was possible to ‘grasp’ several intangible phenomena, which normally leave no evidence." 9/

Ultimately, she identified which parts of the image were made by apprentices (or people with less skill) and which were made by the masters of their craft. 10/

📷: A section of the reliefs. They look homogenous despite the fact that several sculptors were involved

📷: A section of the reliefs. They look homogenous despite the fact that several sculptors were involved

As in Renaissance workshops, it seems that those with less experience worked on simpler bits like torsos and limbs, whilst more experienced artists tackled the complex faces – and corrected the apprentices’ mistakes. 11/

📷: Legs made by apprentices, arrows mark corrections

📷: Legs made by apprentices, arrows mark corrections

Both would work on the time-consuming wigs.

“In one place, a master’s workmanship is so remarkably detailed I feel it seems to say “Look at this! Who can beat me?’,” said Dr Stupko-Lubczynska. 12/

📷: A wig by an apprentice (left) and master (right)

“In one place, a master’s workmanship is so remarkably detailed I feel it seems to say “Look at this! Who can beat me?’,” said Dr Stupko-Lubczynska. 12/

📷: A wig by an apprentice (left) and master (right)

It also offered a chance for on-the-job training - in one area, a master started the wigs and an apprentice attempted to finish them to the same standard. 13/

📷: Wigs made by a master (A) and apprentice (B)

📷: Wigs made by a master (A) and apprentice (B)

“It is generally believed that in ancient Egypt, artists were trained outside of ongoing architectural projects,” she continued, “but my research in the Chapel of Hatshepsut proves that teaching also took place as reliefs were being executed” 14/

Although this did not always work out - the investigation also spotted one wig only half-finished because the apprentice never did his part. 15/

📷: A wig a master started, but the apprentice never finished

📷: A wig a master started, but the apprentice never finished

In some places, the artists did things in a different order, like some of the hieroglyphs near the wigs which appear to have been added later than usual. Perhaps the scribes couldn't reach them on time as the apprentices were still practising. 16/

📷: Where hieroglyphs are weird

📷: Where hieroglyphs are weird

A different team also appears to have worked on each wall, creating subtle differences between the two mirrored reliefs. 17/

📷: Differences between the north and south wall.

📷: Differences between the north and south wall.

Together, these reliefs offer not just a rare glimpse of how ancient Egyptian art was produced, but it was like to work as an artist on these grand building projects - a lot of which might sound familiar to people who work on group projects today. 18/

If you want to find out more, the original research is 🆓:

'Masters and apprentices at the Chapel of Hatshepsut: towards an archaeology of ancient Egyptian reliefs' by Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2…

19/19 🧵

'Masters and apprentices at the Chapel of Hatshepsut: towards an archaeology of ancient Egyptian reliefs' by Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2…

19/19 🧵

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh