After six years our research program in Somaliland has come to an end. Not because we wanted, but because a corrupt officer decided so. An arbitrary decision that has destroyed the only two international archaeology projects in the country.->

During six years we have been the only team to conduct archaeological surveys and excavations in Somaliland. We did it against all odds. With very little funding, but with lots of enthusiasm and great love and respect for the country, its people and its history.->

During six years we discovered new sites and documented in detail many that were already known. We published the results in international journals and made the papers available to all. Every year we sent full technical reports to the Somaliland authorities. ->

We did dissemination work for the Spanish-speaking public, which was largely unaware of the existence of Somaliland and its rich and diverse history. Our work featured in the Spanish version of National Geographic and in the media.->

historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/somalilandia…

historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/somalilandia…

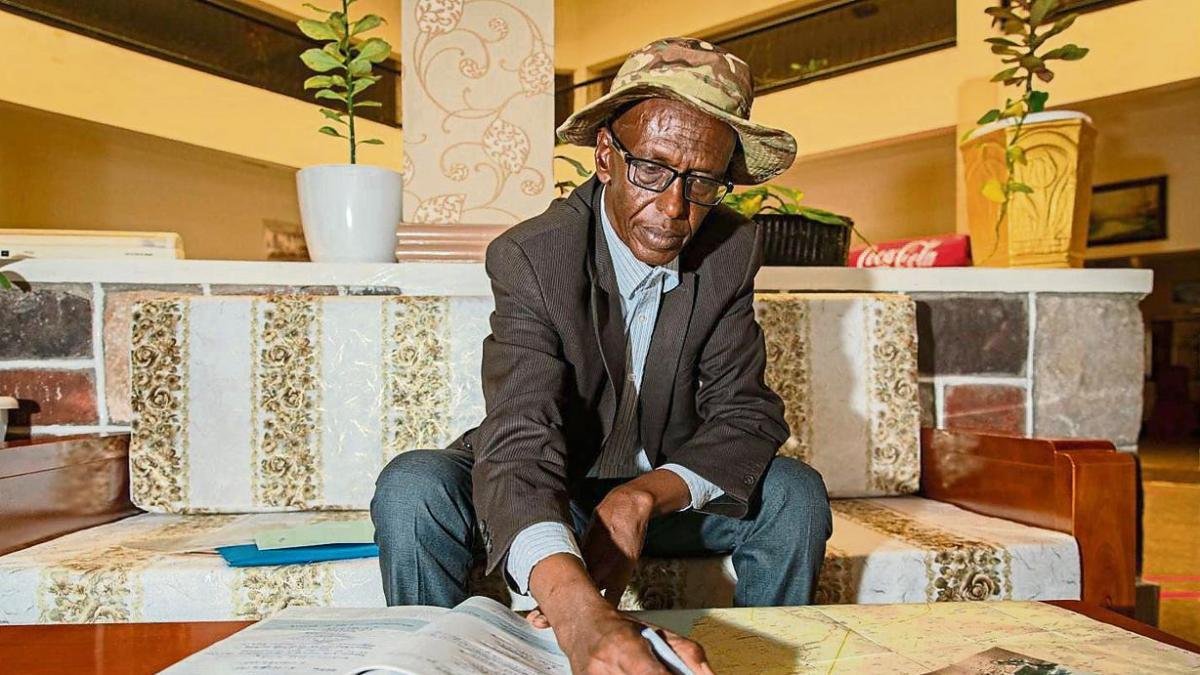

We collaborated with the pioneers of archaelogy in Somalia and Somaliland, such as Mohamed Abdi and Ahmed Dualeh Jama, who have coauthored papers with us. They are the unsung heroes of Somali archaeology and heritage.->

lavanguardia.com/internacional/…

lavanguardia.com/internacional/…

Mohamed Abdi, for instance, documented and mapped hundred of sites. Our project would have been impossible without his assistance. Dualeh was the first Somali to conduct scientific archaeological excavations.->

In 2020 we received for the first time generous funding for doing research and planned large scale excavations and restoration work at the medieval city of Fardowsa. We planned collaborations with the National Museum to be opened in Hargeisa.A book on our research in Somali.->

None of this will ever happen. Because a corrupt officer decided that if he could not get rich with our research program, our program would not be authorized to continue. ->

The corrupt officer was not alone. He was helped by someone else. Someone who started a campaign of defamation against us in the national media. Someone who has done it before.->

Because before us, a French team also worked in Somaliland. They made the site of Laas Geel known outside the country, but they also suffered a campaign of defamation, instigated by the same person. Their work was blocked and they finally left. ->

brill.com/view/journals/…

brill.com/view/journals/…

Needless to say, we hold no grievance against Somaliland and its people. It has been a privilege to study their history. It was an amazing experience, from which we learnt much. We left good friends and fond memories.->

For Europeans, it is ethically and politically complicated to do archaeology in Africa. Because we have an enormous debt with the continent. We have caused immense damage to the people, the land and the cultures of Africa. Neocolonialism still prevails in one way or the other.->

Yet we understand our practice as archaeologists as a way of undoing colonialism -colonial history, at least. We want to tell another story. A story that denounces empire and celebrates a vibrant precolonial past and a promising future. This we tried to do in Somaliland->

We may have failed. But one thing has to be clear: we do not intend, never intended, to be the authorized historical voice in the country. We justed wanted to do our bit. Because we believe history is choral work: the more voices, the better.->

Indeed, as Spaniards, our history has been told by many foreigners. They have often stereotyped us, but they have also made honest contributions to the history of our country. ->

No problem if our work is no longer wanted in Somaliland. We are definitely not indispensable. And we are very happy to see more and more African archaeologists and historians doing amazing work.->

But it is a shame that our project is finished by a combination of mere greed and academic rivalry cloaked as anticolonial struggle. In the end, we all lose. Also the anticolonial struggle.->

We will always be happy to return to Somaliland, a country we admire: an example to the world in many ways. In the meanwhile, we will continue our research in the wider region, trying to understand a fascinating history that deserves to be known widely.

Photos by @AlvaroMin

Photos by @AlvaroMin

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh