Welcome to 🧵3 in this week’s #Jacquerie posts by @mediaevalrevolt . Today I'll talk rebel organization

Medieval revolts often look like undirected mob fury, but most, including the Jacquerie, had formal leadership directing the action - jfb

Medieval revolts often look like undirected mob fury, but most, including the Jacquerie, had formal leadership directing the action - jfb

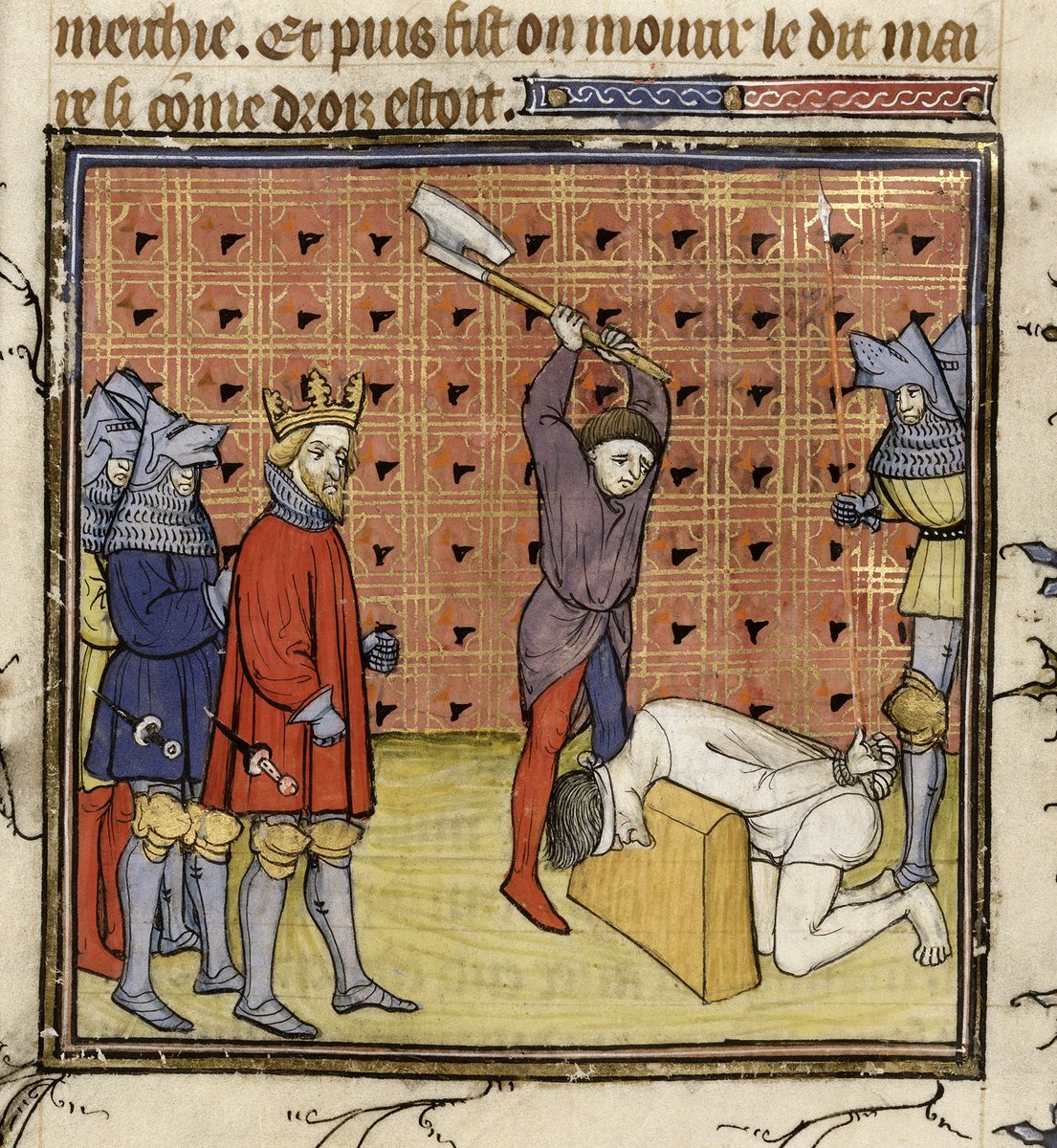

In the #Jacquerie many villages chose local captains to lead them. Local captains reported to a 'General Captain of the Countryside' named Guillaume Calle. The locations of some of these captains and their movements are shown in blue here. - jfb

Calle had a number of close associates - his 'top brass' - who rode with him and who carried his messages and decisions to local contingents (though they did not always do what he said - more on that anon) -jfb

The sources show these leaders tended to be well-off, literate professionals with families. (I discovered in the archives that Guillaume Calle himself was married. Below is a petition from his widow.) - jfb ![[Isabel] wife of the late G...](/images/1px.png)

![[Isabel] wife of the late G...](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FE92KFkXIAQWUxm.jpg)

These men had well defined objectives and sought to coordinate their efforts with the Parisian rebels and other urban sympathisers. Calle wrote to Paris offering aid and sent messengers to villagers ordering them to join Parisian-led attacks. - jfb

But the #Jacquerie was also a grass-roots mov't. Calle had been chosen by an assembly after St-Leu and most of the local captains were also elected by their communities.

Assemblies were key to rebel mobilisation across medieval Europe - jfb

Assemblies were key to rebel mobilisation across medieval Europe - jfb

Rebels naturally used assemblies b/c assemblies were how rural (and urban) communities normally made decisions in the Middle Ages - something I talk about in the Jacquerie book and in this recent chapter in a handbook on medieval rural life - jfb

tinyurl.com/5c7zk4st

tinyurl.com/5c7zk4st

Assemblies gave the rank-and-file had considerable power to shape the revolt. They often chose their leaders and they expected their leaders to 'lead them where they wanted to go' as one group of villagers demanded. - jfb

This caused conflict between rebel leaders and grassroots followers, especially over how much violence to use and whom to target. - jfb

The captains tried to restrain their troops. One said he was always telling them not to set fires, another that he reminded his not to kill anyone. (They forgot) - jfb

On the other hand, the grassroots objected to attacking some targets chosen by the Parisian (like this castle) because the owners were not nobles. Some villagers refused to attack the homes of their own lords, protecting them against rebels from outside the village. - jfb

These disagreements stemmed from the large and varied coalition of commoners behind the #Jacquerie, which was key to its success but also caused its downfall. I'll talk about who the rebels were and how the rebellion fell apart in tomorrow's thread - jfb

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh