Today in pulp I look back at the simple idea that launched a thousand fanzines: Letraset!

Launched in 1959 by Dai Davies and Fred Mackenzie it heralded a graphic design revolution that brought funky fonts to the masses.

Let's take a look... #fontsunday

Launched in 1959 by Dai Davies and Fred Mackenzie it heralded a graphic design revolution that brought funky fonts to the masses.

Let's take a look... #fontsunday

Davis and Mackenzie – both experienced designers – created Letraset as a cheaper alternative to phototypesetting, to help speed up the design process. From humble beginnings in an old factory behind Waterloo station Letraset eventually swept across the design world.

Letraset started life as a wet transfer system: you placed the letter into water, carefully slid off the transfer and tried to apply it to the paper without creasing it. Whilst fiddly it was still quicker than hand-painting your letters.

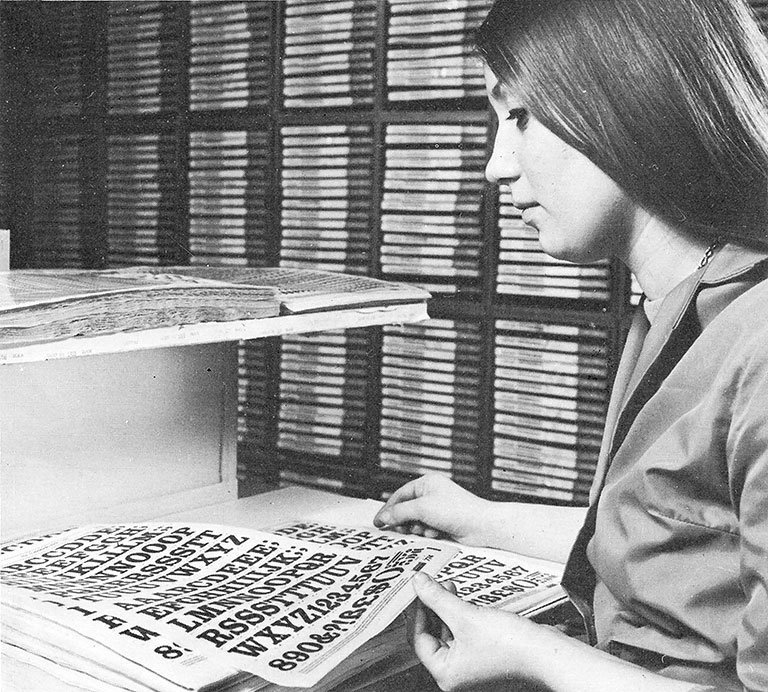

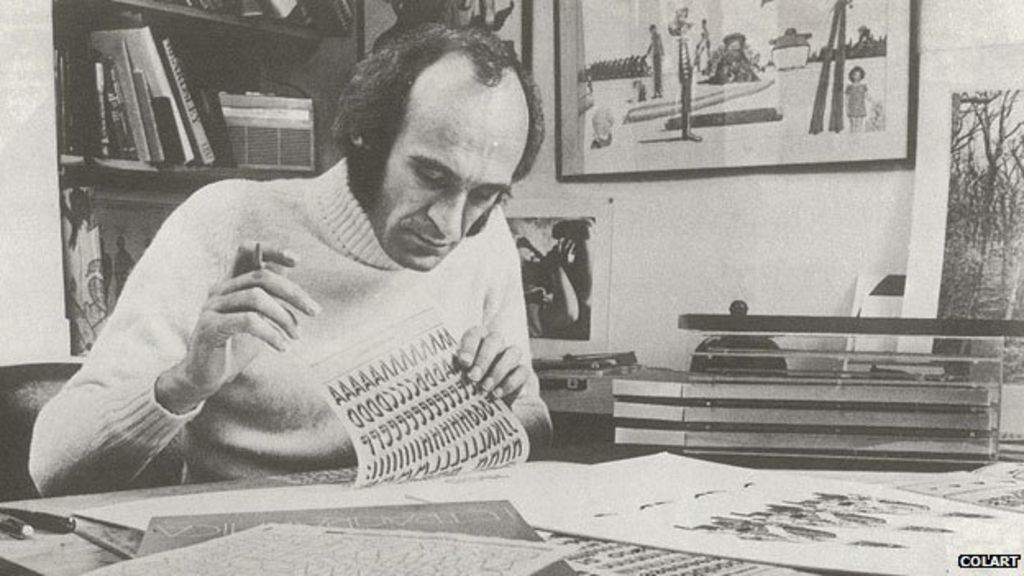

In 1961 Letraset adopted the dry transfer process: letters screenprinted onto a polythene sheet were sprayed over with adhesive. You placed the sheet over the paper and used a pencil to rub over the letter, which detached from the carrier sheet and stuck to the paper. Sometimes.

Letraset stencil masters were cut by hand at a cap height of 15cm from sheets of Rubylith film using a razor blade. A steady hand and keen eye was needed, especially as Letraset produced almost 1,200 typefaces. The original stencils are now at London’s St Bride Printing Library.

However it took some time for Letraset to be taken seriously by designers. Phototypesetting was the industry norm. What Letraset did do was popularise and democratise the world of typefaces and encourage many people to start their own careers in graphic design.

That said, Letraset isn't always easy to use: it’s best to start from the middle letter of the text and work outwards, taking care with spacing as letter widths vary. There's also the nightmare of a letter not fully leaving the contact sheet and tearing as you lifted it off.

There's also a limited number of letters on each sheet, so you often had to cannibalise them to finish your project: cutting the centre bar from an A to make a V, or putting F and L over each other to make E.

Letraset experimented with many new fonts and had a reputation as the go-to resource for ‘now’ lettering. They commissioned almost 500 unique typefaces and in 1970 launched the Letragraphica subscription service to give designers early access to the latest stencils.

Letraset also produced various clip art sheets; these had a very Mad Men feel! In the 1970s it was common to see Punk and New Wave fanzines using these ironically. Letraset (along with cheaper photocopying) helped fuel the boom in home-made magazines and album covers.

The Letraset catalogues were strangely addictive things, but part of the success of the brand was its compulsive nature: why not spend a couple of pounds on a sheet? Especially when it could make your poster / advert / schoolbook stand out from the crowd!

Action Transfers were a spin-off from Letraset fonts; a contact sheet full of colourful images and a cardboard background to make your diorama on. These were licenced to various companies worldwide and covered everything from Star Wars to The Sweeney.

Alas the computer did for dry transfers in the early 1990s: desk top publishing replaced manual layout and Letraset faded from the high street. However as it owned the rights to many of its original fonts which you can still buy these in PostScript format online.

Letraset encouraged many people to start a career in design, and even those who didn’t still learnt a lot about typefaces and layout. From professional designers to DIY publishers it helped fuel a creative boom. Letraset - Twitter salutes you!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh