This Day in Labor History: November 28, 1901. A strike among Cuban cigar workers in Tampa, Florida collapsed after workers inspired by the Cuban revolutionary Jose Martí sought to create a cross-racial organization to resist employer oppression and fight for Cuban nationalism!!

Tampa was a small town in the late nineteenth century. But a growing cigar industry began transforming it into a locally important center. The center of cigar production was in an area called Ybor City.

It was founded by a Cuban cigar manufacturer named Vicente Martinez Ybor, who moved production north in the 1880s to avoid the growing tension in Cuba between the Spanish government and nationalists that would eventually lead to American intervention in 1898.

The cigar industry rapidly became one with a labor activism and had already seen a major strike in 1887. The Cuban cigar workers saw themselves as craftsmen, not industrial workers.

They resented any employer attempts to rationalize production and impose what was becoming modern corporate efficiency upon them. Ideas of socialism and anarchism were also being shared by these workers, creating a growing class consciousness in their new nation.

By 1900, Cubans made up about 20 percent of Tampa’s population and maybe 15 percent of those were Afro-Cuban. Meanwhile, the whites there were typical of the Jim Crow South. These workers may have been necessary but they definitely were not seen as equal.

Cigar workers built a political culture in Tampa. For one, the legendary Cuban revolutionary Jose Martí spent a lot of time in Tampa working on this issue. He urged the workers to put Cuban nationalism over their racial divides.

Speaking from the steps of a Ybor City cigar factory in 1891, he told the workers, “I know of black hands that are plunged further into virtue than those of any white man…Others may fear him; I love him. Anyone who speaks ill of him I disown, and I say to him openly: You lie.”

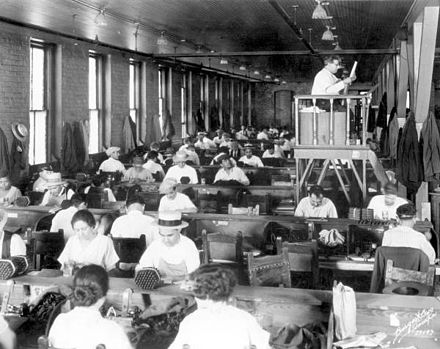

In fact, the image above is of Martí speaking at a Tampa cigar factory in 1893. This Cuban nationalism soon tied in with labor activism.

In May 1901, the cigar workers protested because they city had not repaired a destroyed bridge that connected where they lived to where they worked.

This meant they had a complicated and very long commute to work that included multiple forms of transportation, including using a ferry.

That was ended fairly quickly, with the mayor pledging to fix the bridge. But it laid the groundwork for another round of worker activism soon to follow.

Later that year, employers decided to find a way to bust the burgeoning unions in Tampa cigar shops by establishing new factories in Jacksonville and Pensacola so that they could play the different workers off each other.

This attempt to enforce the open shop forced the workers on strike. The Cubans led what became called La Resistencia, but they weren’t the only ones in these factories by this point.

There were also growing numbers of Italian workers and they too became strike leaders. Many strikers left Tampa to take jobs elsewhere and then sent what money they could back to help their comrades.

Probably 5,000 workers participated in the strike. The real issue for them was worker control over the means of production, which is more about literal worker control over how the cigars were made than who actually owned the factory.

They wanted a closed shop and guaranteed job security in the face of an industry that was increasingly precarious for workers.

They also wanted to act against the traditional craft union in the industry, the Cigar Makers International Union, a white-dominated union affiliated with the American Federation of Labor that looked at Cuban nationalism with contempt and as irrelevent for organizing in the US.

La Resistancia began to demand that CMIU members be expelled from the factories as well.

This all led the Tampa elite to go to extreme measures. In early August, a committee of local elites formed and convinced the police, who did not take much convincing, to arrest strike leaders on dubious grounds.

But see, they didn’t take them to prison. They took them to Honduras. The strike leaders were loaded onto a boat, shipped to the Honduran coast, and dumped there, warned never to return to Tampa.

Moreover, at least according to long-running rumors, the police didn’t do the shipment themselves. They contracted out with the Italian mafia in New York, paying them $10,000 for it.

Local newspapers openly bragged about the Honduras action, if not contacting the mafia.

La Resistancia demanded that state and federal authorities investigate the deportations, but government completely ignored them, far more concerned with what Duke Tobacco thought than a bunch of Cubans.

In fighting this battle, La Resistancia channeled the words of Jose Martí and argued that all races must come together to fight capitalism. For instance, its newsletter, La Federacíon, it stated:

"Current human morality, in general practice, supports a contradiction analogous to that found by Christians in the Bible. Without delving into the matter, purely in intellectual purity, it repeats that “all men are brothers,” ........

.....but when the black and white [are] face to face in conflict created by the interests, voluntarily forget that brotherhood – completely theoretical – ......

.....they are drawn by that old instinct of hatred that makes an alien a being of quite different origin, belonging to a different and hostile species."

Despite the brave struggle of these workers to create cross-racial solidarity, there was no real way a bunch of impoverished Cuban and Italian workers could overcome this kind of resistance.

The city elites continued importing strikebreakers and arresting strikers for anything, usually vagrancy, that “crime” used throughout much of American history by the rich to suppress resistance from the poor.

Moreover, the ability of these workers to attract any sizable number of workers from the African-American community outside the factories was basically nonexistent.

They couldn’t really stop the technological advancements of the factories and the nation as a whole was itself extremely anti-union and anti-black at the same time, making a union calling for all races to resist capitalism together extremely unpopular.

Finally, on November 28, La Resistencia caved. The strike ended and the workers returned to the factories on January 2, 1902, when the owners decided to start back up.

But the long tradition of labor activism among Cuban cigar workers would remain strong and would lead to more strikes in the future.

I borrowed from Irvin Winsboro and Alexander Jordan’s “Solidarity Means Inclusion: Race, Class, and Ethnicity within Tampa’s transnational Cigar Workers’ Union,” published in Labor History in 2014, to write this thread.

Back Tuesday to discuss the WTO protests at the Battle of Seattle.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh