A new paper: “Removal of Context: Blackstone, Limited Monarchy, and the Limits of Unitary Originalism,” Yale J. Law & Humanities, 2022.

I found many errors in unitary executive amicus & scholarship on Blackstone & other historical sources. Thread:

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

I found many errors in unitary executive amicus & scholarship on Blackstone & other historical sources. Thread:

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

2/ I think these errors are in good-faith. This material is complicated, the 18th c. terms are obscure.

But that's the point:

Originalists claim supremacy as the most reliable & objective method, on the eve of overturning Roe/Casey. These errors should give us all pause...

But that's the point:

Originalists claim supremacy as the most reliable & objective method, on the eve of overturning Roe/Casey. These errors should give us all pause...

3/ Most of these errors are more than small interpretative errors in a SCOTUS amicus brief.

They often get the big points backwards, such as Blackstone's work as fundamentally contrary evidence against their theory and historical claims.

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/11/30/rem…

They often get the big points backwards, such as Blackstone's work as fundamentally contrary evidence against their theory and historical claims.

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/11/30/rem…

4/ I wrote to the Seila amicus brief scholars on Oct. 13. I've had good conversations with most of them. This paper does not come as a surprise. I also acknowledged I've made good-faith errors in an amicus & they were generous about it then:

originalismblog.typepad.com/the-originalis…

originalismblog.typepad.com/the-originalis…

5/ A long series of posts will explain these errors.

The 1st:

Their amicus tries to find a general royal removal power in Blackstone, but it just isn't there.

Instead, they misinterpret "dispose" as "remove," rather than "distribute" "grant" "appoint": shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/11/30/rem…

The 1st:

Their amicus tries to find a general royal removal power in Blackstone, but it just isn't there.

Instead, they misinterpret "dispose" as "remove," rather than "distribute" "grant" "appoint": shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/11/30/rem…

6/ This error is revealing. There seems to be a mix of confirmation bias and a set of assumptions: If you're looking for removal, you might jump on the word "dispose." But the rest of Blackstone and even the U.S. Constitution itself use the word to mean "grant" or "dispense."

7/ The most serious error is misquoting Blackstone in their Seila Law amicus brief:

Moving the word "not" so that the Blackstone quote more or less takes on the opposite meaning, from his explicit uncertainty about offices to their claim about removal.

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/11/30/rem…

Moving the word "not" so that the Blackstone quote more or less takes on the opposite meaning, from his explicit uncertainty about offices to their claim about removal.

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/11/30/rem…

8/ Compare their brief (left) to Blackstone (right):

Amicus wrote "Blackstone explained that these offices are not" objects of our laws.

Blackstone actually wrote "I do not know that..."

Their brief moved the "not" to change the meaning from *against* their theory to *for it*.

Amicus wrote "Blackstone explained that these offices are not" objects of our laws.

Blackstone actually wrote "I do not know that..."

Their brief moved the "not" to change the meaning from *against* their theory to *for it*.

9/ Remarkably their brief suggests "the lord treasurer, lord chamberlain,

the principal secretaries" and “his majesty’s great officers of state” were comparable to the Constitution's many, many "principal officers."

This was the Crown's cabinet. It's a basic error.

the principal secretaries" and “his majesty’s great officers of state” were comparable to the Constitution's many, many "principal officers."

This was the Crown's cabinet. It's a basic error.

10/ More to come, but I'll pause on this passage of their self-certainty:

The brief says our historical interpretation "is simply a disagreement with the Constitution."

In other words, their unitary view is "the Constitution."

I'm still taken aback every time I read it:

The brief says our historical interpretation "is simply a disagreement with the Constitution."

In other words, their unitary view is "the Constitution."

I'm still taken aback every time I read it:

11/ Why is an amicus brief a big deal?

These co-authors are major figures in the originalist world. Even if the Roberts Court didn't cite it, Roberts's opinion closely tracked their argument.

Thomas cited Prakash's Decision of 1789 article, which has many errors.

These co-authors are major figures in the originalist world. Even if the Roberts Court didn't cite it, Roberts's opinion closely tracked their argument.

Thomas cited Prakash's Decision of 1789 article, which has many errors.

12/ If the Vesting clause, the Take Care clause, nor the Decision of 1789 support the unitary theory, it's not clear what is left of its originalist basis.

I document Prakash's misreadings from the First Congress here in "The Indecisions of 1789":

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

I document Prakash's misreadings from the First Congress here in "The Indecisions of 1789":

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

13/ "Faithful Execution and Article II" (w/ Leib & @andrewkent33) shows that the Take Care clause & Oath had an original public meaning of limiting discretion & imposing duties.

A duty-binding clause would not imply powers that exceeded the duties:

harvardlawreview.org/2019/06/faithf…

A duty-binding clause would not imply powers that exceeded the duties:

harvardlawreview.org/2019/06/faithf…

14/ "Vesting" (@StanLRev 2022) similarly shows that the original public meaning of the word "vest" did not imply indefeasible or exclusive official powers, as formalists assume. Dictionaries & digital collections show that "vesting" was a simple grant:

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

15/ This thread focuses on the many misreadings in Prakash's "A New Light on the Decision of 1789."

The larger point: the unitary executive is so historically weak that its theorists had to stretch & misinterpret sources to build a case.

With these errors set aside, what is left?

The larger point: the unitary executive is so historically weak that its theorists had to stretch & misinterpret sources to build a case.

With these errors set aside, what is left?

16/ Here is a summary of Prakash's misreadings or miscategorization of sources from my paper "The Indecision of 1789." This thread will compare his description of sources with a photo of the original source:

17/ The bigger picture is the oddity of this whole unitary executive word search/world search.

It's not in the text of the Constitution, nor the Ratification debates...

So go back to Blackstone to find it?

And the post-Ratification Congress?

And even then, they can't find it.

It's not in the text of the Constitution, nor the Ratification debates...

So go back to Blackstone to find it?

And the post-Ratification Congress?

And even then, they can't find it.

18/ The "Decision of 1789" is a myth, forged by Madison as a legislative trick when he didn't have the votes for his very temporary theory (and never approached the modern extreme theory), then spread by presidentialist insiders like Adams & Marshall, then Taft and Roberts...

19/ From Taft's mythologizing in Myers (1926) and Roberts's Free Enterprise (2010), the unitary theory of unchecked removal was a fringe idea.

Prakash's 2006 article signaled a revival. He clerked for Thomas. Thomas cited it.

It is full of errors.

scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewconten…

Prakash's 2006 article signaled a revival. He clerked for Thomas. Thomas cited it.

It is full of errors.

scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewconten…

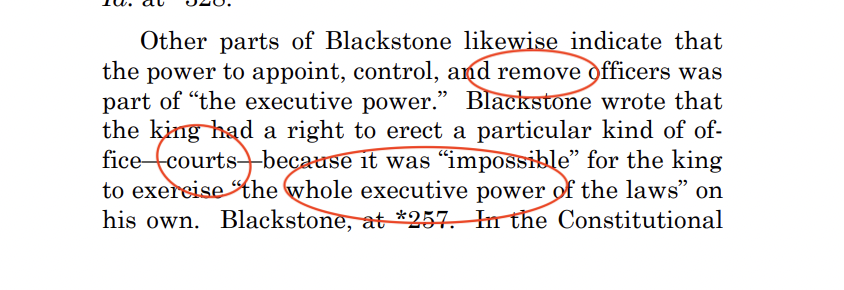

20/ First let's cover some other errors that overlap in the amicus brief and in Prakash's other work.

This paragraph in their amicus brief p. 9, citing Blackstone, seems to contradict their basic point. The full passage in Blackstone is even more problematic.

This paragraph in their amicus brief p. 9, citing Blackstone, seems to contradict their basic point. The full passage in Blackstone is even more problematic.

21/ Here is the Blackstone passage, describing courts as assisting the king with "executive" power. Amicus quoted but missed the contradiction:

English judges were part of the executive power, but judges were protected from removal, a major problem for the unitary theory:

English judges were part of the executive power, but judges were protected from removal, a major problem for the unitary theory:

22/ This brief is staggeringly confused.

The unitary scholars got lost in both the forest and in the trees of Blackstone:

They repeated misquote & misinterpret Blackstone's details, and why is Blackstone's English king the model for the president anyway?

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/12/06/rem…

The unitary scholars got lost in both the forest and in the trees of Blackstone:

They repeated misquote & misinterpret Blackstone's details, and why is Blackstone's English king the model for the president anyway?

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/12/06/rem…

23/ To his credit, @ilan_wurman acknowledged the “dispose” error but rationalized his misquotation of Blackstone’s “I do not know…” by saying it was ambiguous & he got the gist right.

I disagree on both. But he’s also dismissive of new evidence…

yalejreg.com/nc/some-though…

I disagree on both. But he’s also dismissive of new evidence…

yalejreg.com/nc/some-though…

@ilan_wurman:

“I am not persuaded that the brief’s central claim about English law & practice relating to the king’s removal power is incorrect, or even materially in doubt. Jed so far hasn’t pointed to specific evidence to the contrary”

To the contrary:

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/12/06/rem…

“I am not persuaded that the brief’s central claim about English law & practice relating to the king’s removal power is incorrect, or even materially in doubt. Jed so far hasn’t pointed to specific evidence to the contrary”

To the contrary:

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/12/06/rem…

24/ For what it’s worth, I give @ilan_wurman credit for replying and engaging.

I don’t think it’s fair that he has to carry this responsibility alone.

I think the co-authors need to address these errors, especially Sai Prakash, who has made the most interpretations of sources.

I don’t think it’s fair that he has to carry this responsibility alone.

I think the co-authors need to address these errors, especially Sai Prakash, who has made the most interpretations of sources.

25/ I meant that Prakash has made the most *misinterpretations.* I identified many of these misreadings in May 2020.

See Appendix for specific errors in his article that amicus and Justice Thomas cited:

See Appendix for specific errors in his article that amicus and Justice Thomas cited:

https://twitter.com/jedshug/status/1465803449870733328

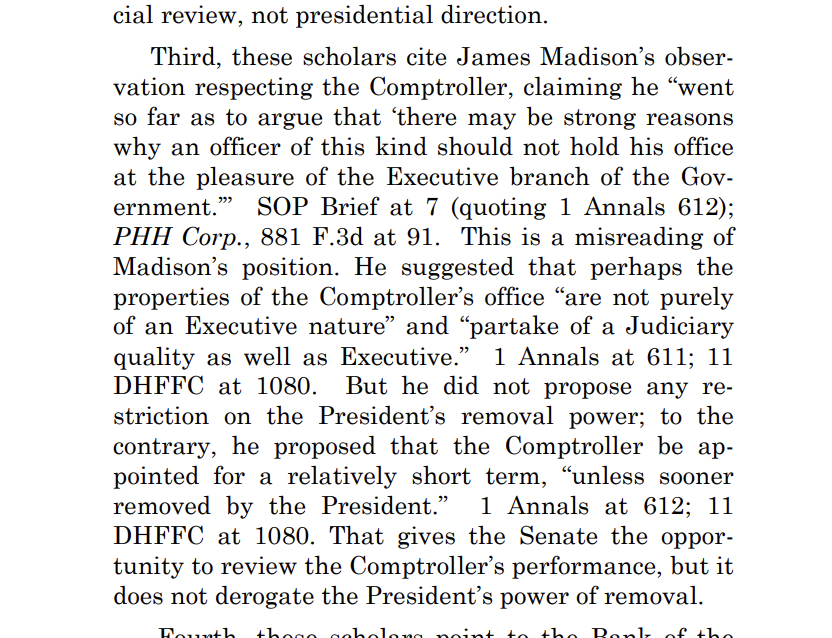

26/ Among other misreadings of the First Congress (the mythic "Decision of 1789"), amicus also erroneously claimed that Madison "did not propose any restriction on the President’s removal power." (p. 24) This error is more understandable, but it is nevertheless wrong:

27/ Building on outstanding new research by @Jane_C_Manners & @LevMenand, I show how Madison proposed protecting the Comptroller from presidential removal "at pleasure" - and his colleagues understood him & then revealed the "Indecision of 1789" (p.37-43)

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

28/ FIN

A final blogpost to wrap up this series, before starting the next thread on Sai Prakash’s many misreadings and miscategorizations to wrongly claim a “Decision of 1789.”

An example of originalism hubris after so many errors:

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/12/07/rem…

A final blogpost to wrap up this series, before starting the next thread on Sai Prakash’s many misreadings and miscategorizations to wrongly claim a “Decision of 1789.”

An example of originalism hubris after so many errors:

shugerblogcom.wordpress.com/2021/12/07/rem…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh