Reading another eg of conservative voices in ed suggesting that seeking to diversify history ed, and ensure it better reflects scholarship, is a pursuit of niche interests, at the expense of improving edu for all.

Why this claim is false: a thread /1

fordhaminstitute.org/national/comme…

Why this claim is false: a thread /1

fordhaminstitute.org/national/comme…

First @rpondiscio classifies the pursuit of “teaching history honestly” - an approach to history which suggests e we need to acknowledge racist and imperial roots in schools - as a “luxury belief”. Something of concern to the woke, young staffers but not the pupils they serve /2

He then goes on to claim that on 15% of 8th graders in the US “are proficient in history”, implying that time would be better spent “teach[ing] history.” The pursuit of a critical approach to a diverse past is suggested as a barrier to learning - a social injustice /3

I should say that variations on this claim have been a @educationgadfly theme for a while now, something @ArthurJChapman and I have discussed in the past - files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED516… /3a

Before we go on, I think it is worth noting that Pondisco’s luxury is someone else’s fundamental right. For eg., as @debreese or @DavidTreuer have argued, many US history textbooks have ignored Native voices or told a distorted narrative of Native presence. /4

Every child has the right to go beyond the traditional retelling of the creation and development of the US; to critically reflect on that interpretation; to see a messier, more diverse, and more complex history in which erstwhile silenced voices can be heard /5

Despite this, some states are taking active measures to preserve history as myth (see NH example here). This is terrible for students who want to learn anything resembling the discipline of history, not to mention for justice. /6

Back to the @educationgadfly piece: Such bold claims got me interested. Who exactly was talking about the proficiency of 8th graders in history? By what metrics? And were “young, woke” teachers really preventing young people learning “real” history or hampering their learning? /7

Light digging revealed that being “proficient” in history was actually a reference to the NEAP assessment system used in some US schools. “NEAP Proficient” is a specific grading descriptor. In fact 2/3 exceed the NEAP pass rate - a point the article fudges for effect. /8

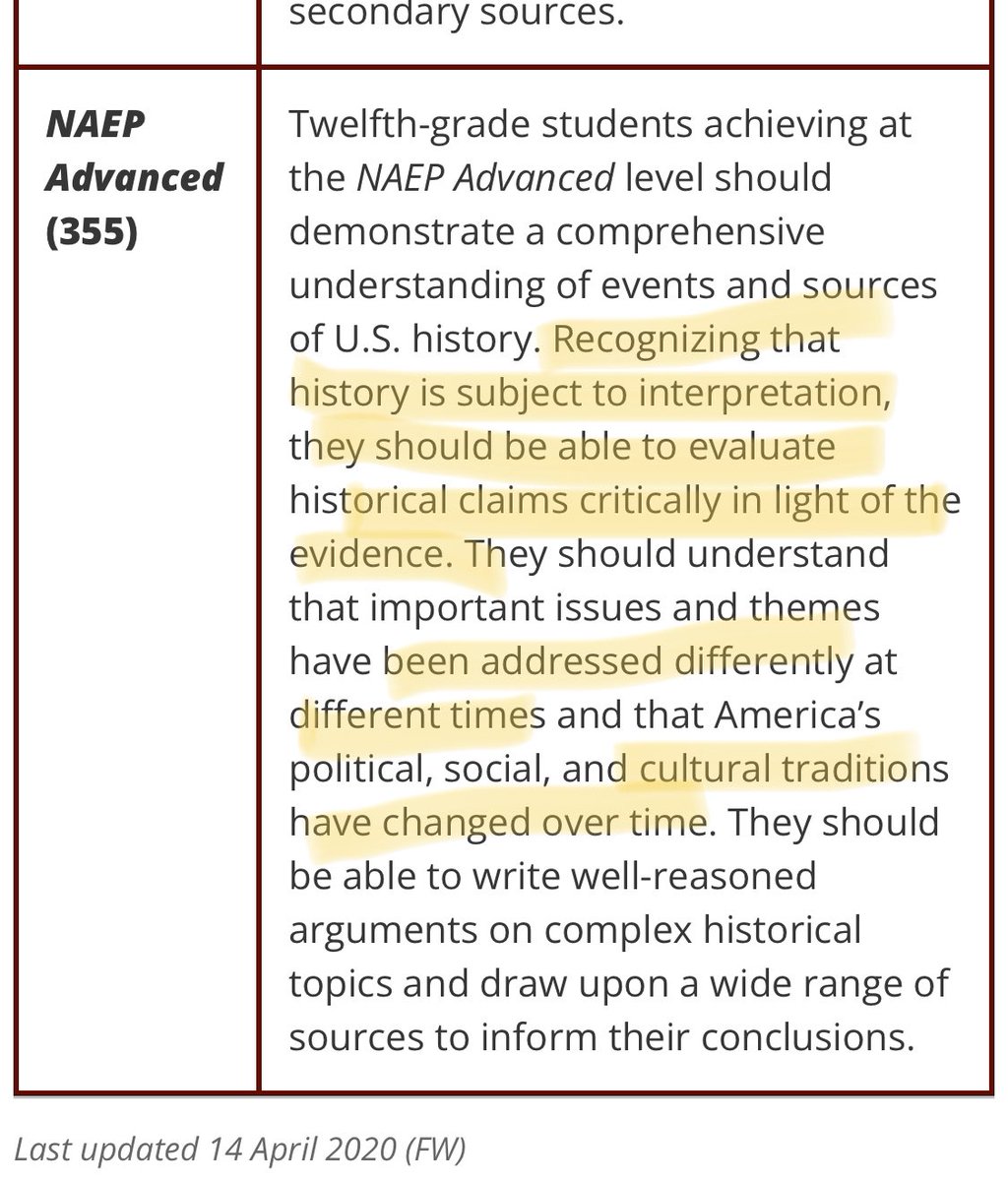

So the next q is whether a “woke” focus is preventing students from attaining the “proficient” grading? A brief exploration of the descriptors is very revealing. I have highlighted some relevant progression points in the next few tweets /9

First what is evident is that for students to move from a “Basic” to “Proficient” grade, they need to recognise and understand the diversity and diverse experiences of the American people. So a refocusing of US history, as many now champion, would likely help not hinder /10

In fact one of the sample 8th grade qus asks students to reflect on the typical and atypical experiences of enslaved people before the creation of the US Constitution - an issue which the hard right 1776 Project attempted to ignore and which seldom appears in trad narratives /11

If we move on and look at “Advanced” descriptor for 8th Gd we find that an ability to draw analogous connections between past and present events is rewarded. This is precisely the kind of thing which teachers, inspired by things like the 1619 Project have been trying to do. /12

Finally, the 12th grade “Advanced” descriptor demands students recognise the interpreted nature of history and to reflect critically on claims, amongst other things. All of this fits better with the re-evaluation of history teaching which is dismissed as “luxury” /13

By any stretch then, failing to take students beyond a rote learning of traditional narratives and myths would do little to improve student attainment in the NEAP grading system. Indeed, just “teach[ing] history” traditionally would seem to risk contributing to the problem /14

But there is another layer of issues here. One thing you might note for instance is that the NEAP history scores are remarkably static over time. Roughly 14-17% have attained the “Proficient”’grade since 1994. This made me curious again. How does the grading work? /15

One might assume the “Proficient” standard is criterion referenced. However, the NEAP uses a scaled and standardised score to produce a weighted distribution. The result is to a roughly similar proportion of students at each standard year on year. /16

Because this is a planned distribution, the % of students attaining the “Proficient” each year is likely to only ever vary by a few %. So the implied notion that somehow all students should be “Proficient” is virtually statistically impossible. /17

Second, it is hard to claim there is a crisis in history by comparison to other subjects as scores are not comparable. So there is no evidence to suggest that either there is a history education crisis, nor that it would be solved by ignoring current debates in history ed /18

To use the claim that “a mere 15% of 8th graders are proficient in history” to suggest teachers need to spend less time helping students to critically engage with received narratives and more time teaching traditional content is a gross misrepresentation and a distraction! /19

History teachers play a crucial role in helping students critically engage with the power and complexity of the past, and how it is presented. Too many voices want to obscure this. But unless we stay true to that principle, we will never properly do justice to history. /20

For more thoughts on why we need to critically reevaluate what history we teach, and how, you might like to watch my mini series on “Communities of Principle” in history education. To fail to take action is to fail young people. andallthat.co.uk/blog/communiti…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh