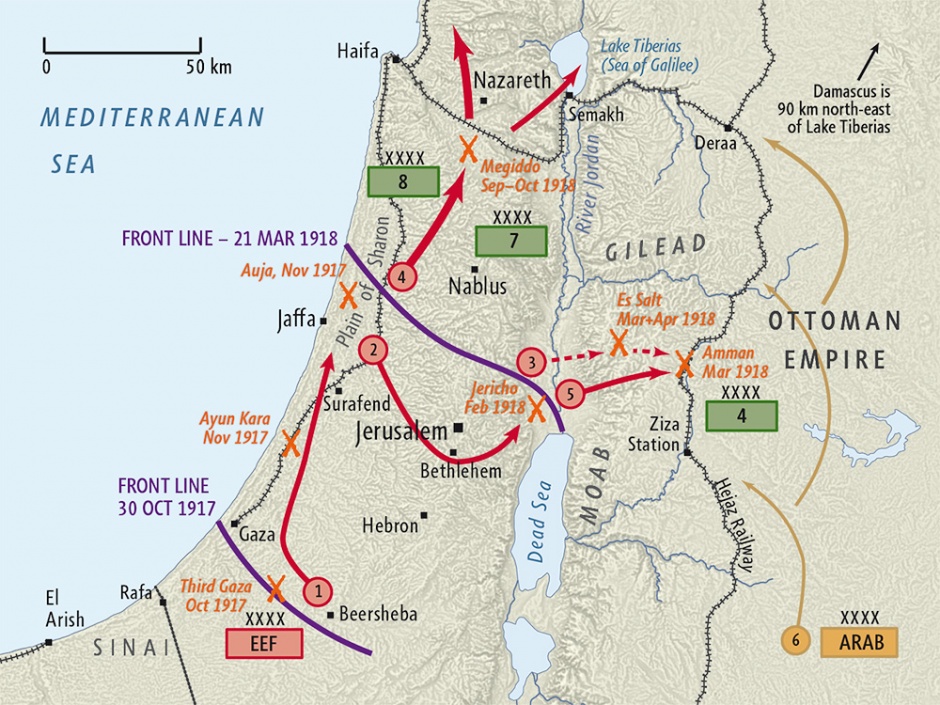

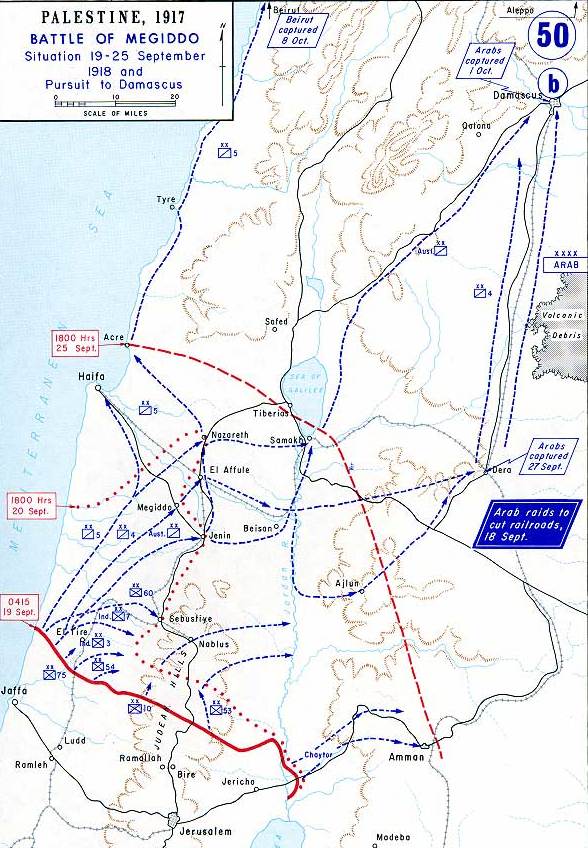

On 19 September 1918, General Allenby launched an offensive to break through Ottoman lines in northern Palestine, the Battle of Megiddo.

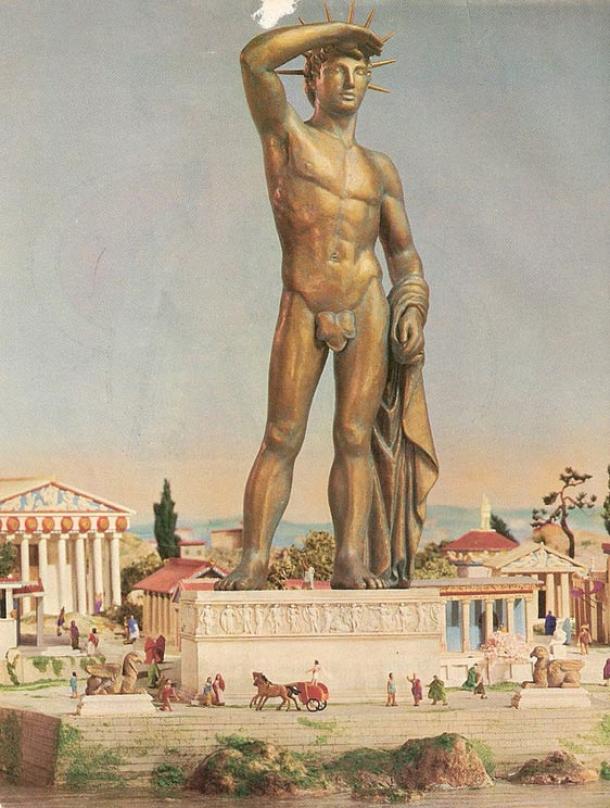

He was inspired by Thutmose III's conquest of Canaan, in which the pharaoh attacked from an unexpected direction in a battle of the same name.

He was inspired by Thutmose III's conquest of Canaan, in which the pharaoh attacked from an unexpected direction in a battle of the same name.

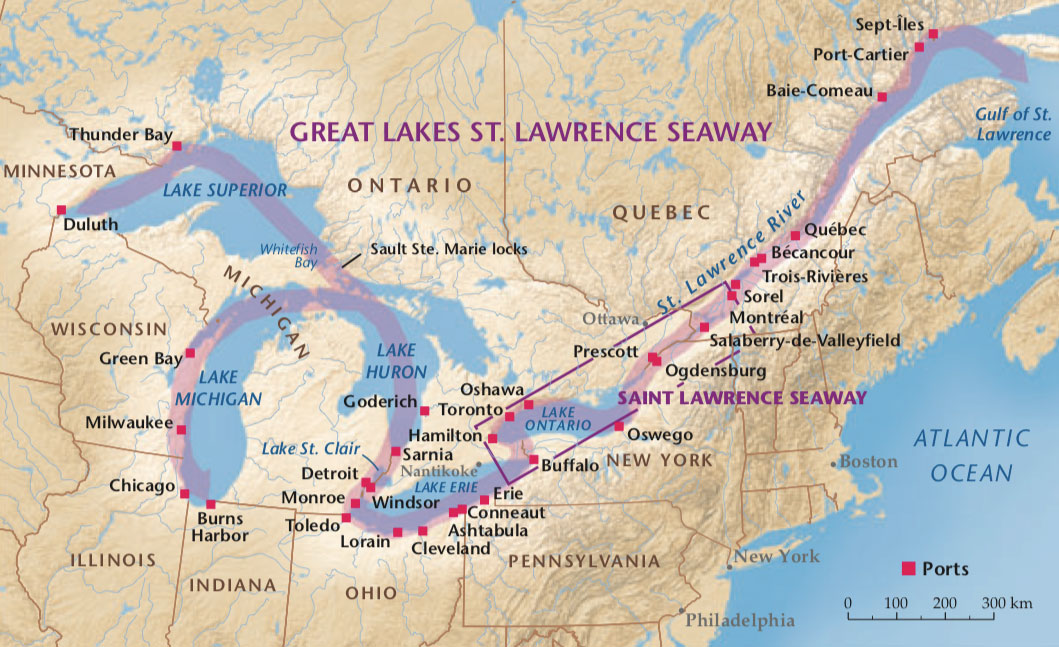

The Jezreel Valley is a broad, fertile plain that runs through modern Israel, connected at the northwest via the Kishon River to the sea, and in the southeast to the Jordan. In ancient times, it sustained a large population and was an important center of political power.

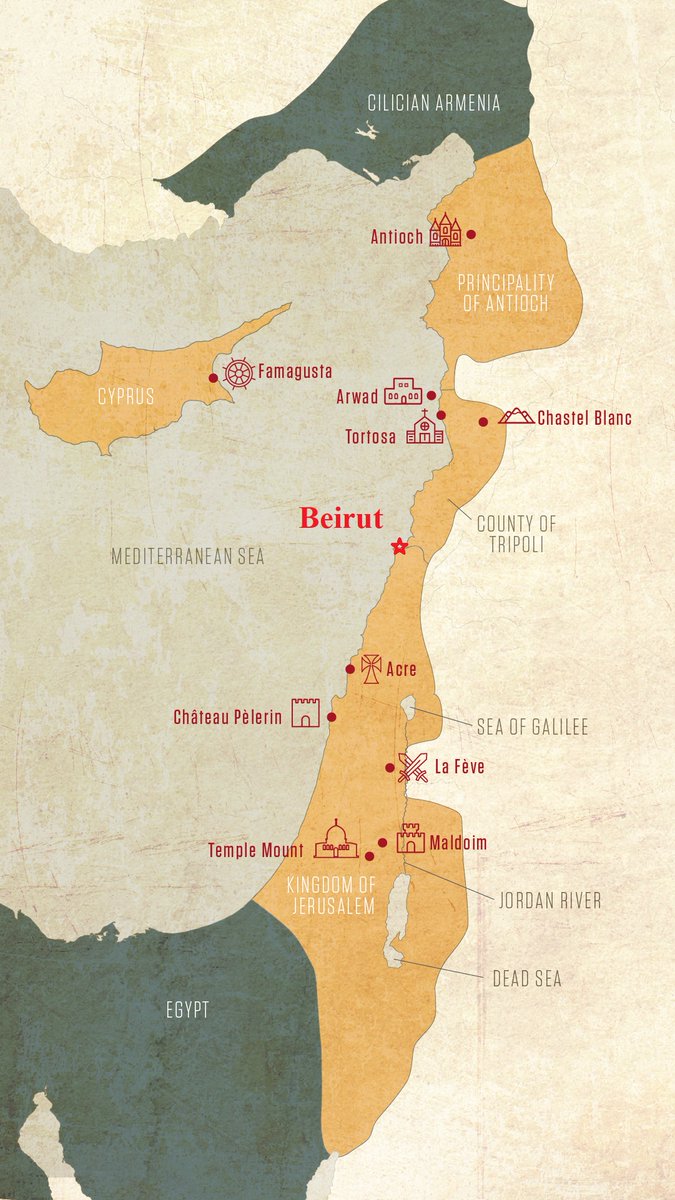

In 1457 BC, Thutmose III marched out to quell a revolt by his Syrian and Canaanite vassals. They had massed their forces in the Jezreel, protected from the coastal plain to the south by the Mount Carmel range.

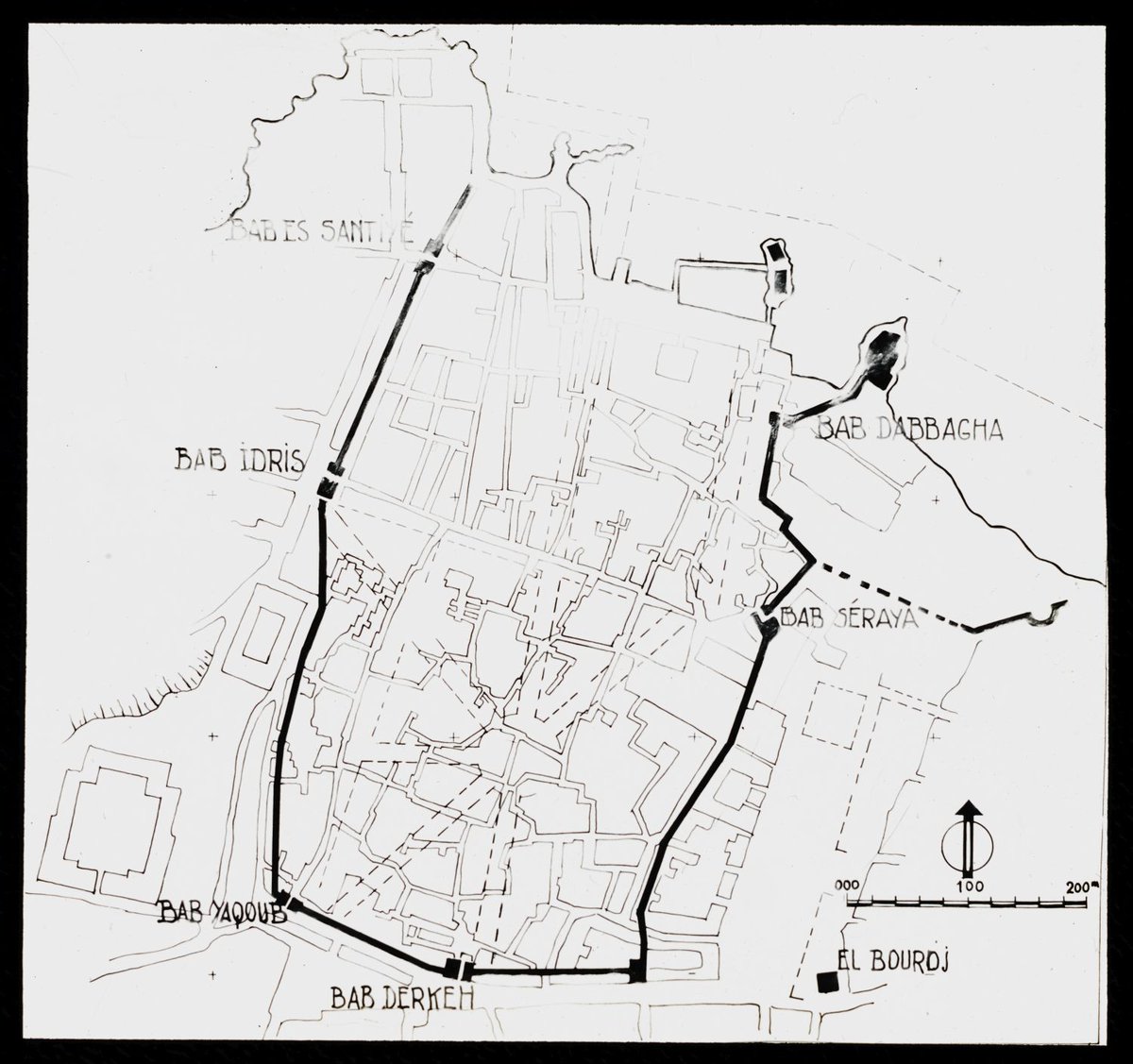

The rebels had concentrated around the strong hillfort of Megiddo, which guarded the southwestern edge of the valley. But they also sent out detachments to block the main approaches through the mountains.

There were two principal routes into the Jezreel. The easiest route ran east into the southern end of the valley; a more difficult route ran to the north.

But there was also a third route, wide enough for only one man to pass at a time, which led straight to Megiddo itself.

But there was also a third route, wide enough for only one man to pass at a time, which led straight to Megiddo itself.

Thutmose’s scouts informed him that the central route was unguarded, so he took a gamble and took the more direct but more hazardous approach. He took the rebels completely by surprise, routed their army, stormed Megiddo, and subdued the region.

Thirty-four centuries later, Edmund Allenby found himself in a similar position as he pushed up from Egypt into Ottoman Palestine.

Geography is unchanging, and presents the same military difficulties across the ages. In this case: how to break through the Mount Carmel range.

Geography is unchanging, and presents the same military difficulties across the ages. In this case: how to break through the Mount Carmel range.

Allenby realized that the key to success was cutting off the two defending armies from their headquarters at Nazareth. But the mountains of Palestine posed the same problem as the trenches of the Western Front: how to exploit the initial assault to break through?

The key to Nazareth lay in reaching the Jezreel Valley as quickly as possible. So as soon as the initial British assault broke through the Ottoman forces in the coastal plain, Allenby sent his cavalry through the same valley Thutmose took near Megiddo.

It was a brilliant success, and collapsed the entire Ottoman lines. The Seventh Army under Mustafa Kemal—the future Ataturk—was in an untenable position around Nablus and withdrew, yielding the entire Jordan Valley to the British and opening the road to Damascus.

There was very little fighting around Megiddo itself, but Allenby named the battle after that location because it played such an important role in his ultimate success. There was also another reason, however....

Geography is a constant throughout history, and the same factors that made Megiddo important to Thutmose III and Edmund Allenby have made it important to many others—there have been several battles of Megiddo. The battlefield was so important, in fact….

....that it was prophesied to be the site of the final apocalyptic battle in the Book of Revelations, where it is called Armageddon—“Har-Megiddo”. Allenby, not shy about burnishing his reputation, chose the name for its Biblical overtones.

A great discussion of Megiddo in the Bronze Age with @digkabri, the excavator of the site, in which he mentions Thutmose's influence on Allenby:

pod.co/experts-in-his…

pod.co/experts-in-his…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh