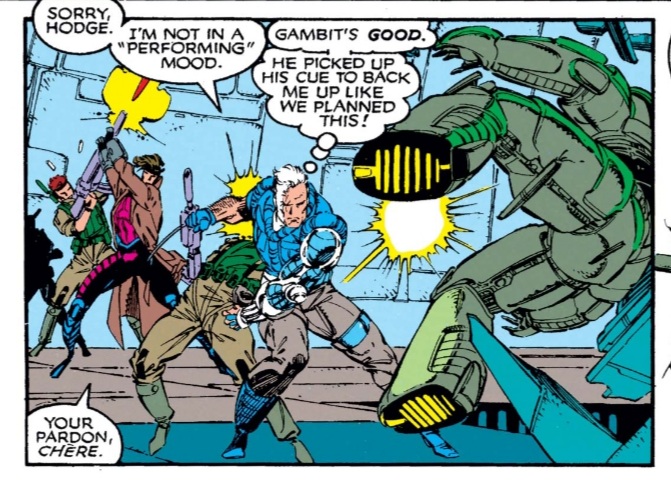

Amidst the chaos of UXM #272, Claremont gives Gambit a moment to shine at a time when he was still largely an unknown to both the X-Men and the readers. In addition to saving the team, Gambit’s actions relay a ton of information about his character. #xmen 1/7

Gambit plays an essential role in the X-Men’s escape, first by perceiving and supporting Cable’s own attempt, then by using that as a ruse by which he can obtain the means to execute a secondary escape attempt thereafter, at great personal cost. 2/7

Cable attacks their jailers and Gambit immediately follows suit. Cable is, however, talked down by Hodge threatening Psylocke. When Hodge fires at Cable anyway, Gambit heroically dives to save Cable, taking a spike to the thigh in the process. 3/7

This is the ruse. Gambit later uses the spike in his thigh as a tool to pick his own manacles and free himself and the rest of the X-Men. In the process, he shows intelligence, duplicity, incredible agility, and a rare force of will (all key Gambit character attributes). 4/7

His initial role in the first escape attempt also shows him forcing himself on a female guard with a non-consensual kiss, another key character attribute with some villain-shading, though that’s not always clear in the context of Claremont’s writing (it happens a lot). 5/7

Claremont also gives Cyclops a character beat here with Scott recognizing, immediately, that Gambit was running a con with the spike – a sort of game recognizing game moment. 6/7

It is also interesting that prior to Scott’s observation, Gambit would have happily pretended he was just injured in sacrifice for a teammate. This is at a time when Gambit’s intentions were unknown, and winning over the X-Men (if he was to be a spy) would have made sense. 7/7

Just to editorialize, I accept that X-Tinction Agenda was a mess, but Claremont's 3 issues were each a masterclass on characterization during frenetic action - some of his best work in that regard, imho.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh