1/

Get a cup of coffee.

This is a joint thread; Sahil Khetpal (@skhetpal) and I wrote it together.

In this thread, we'll walk you through various "Return Ratios" -- ROA, ROE, ROIC, ROCE, etc.

This will help you judge business quality better, and hence invest better.

Get a cup of coffee.

This is a joint thread; Sahil Khetpal (@skhetpal) and I wrote it together.

In this thread, we'll walk you through various "Return Ratios" -- ROA, ROE, ROIC, ROCE, etc.

This will help you judge business quality better, and hence invest better.

2/

Businesses generally work like this:

a) Raise *capital* -- equity, debt, float, etc.

b) Turn this capital into *assets* -- new products, software, inventory, factories, etc.

c) Generate *cash* from these assets. And,

d) Over time, *return* cash back to owners.

Businesses generally work like this:

a) Raise *capital* -- equity, debt, float, etc.

b) Turn this capital into *assets* -- new products, software, inventory, factories, etc.

c) Generate *cash* from these assets. And,

d) Over time, *return* cash back to owners.

3/

*Owners* of such businesses have 2 main concerns:

One: How much cash do they have to PUT IN?

And,

Two: Once they PUT IN this cash, how much cash can they TAKE OUT over time?

The *less* they have to PUT IN, and the *more* they can TAKE OUT, the happier they are.

*Owners* of such businesses have 2 main concerns:

One: How much cash do they have to PUT IN?

And,

Two: Once they PUT IN this cash, how much cash can they TAKE OUT over time?

The *less* they have to PUT IN, and the *more* they can TAKE OUT, the happier they are.

4/

Imagine we have 2 businesses: A and B.

A is a "capital heavy" business -- like a telecom operator. It needs $20 in assets to produce $1 of annual earnings.

B is a "capital light" business -- like a software company. It needs only $2 worth of assets to earn $1 annually.

Imagine we have 2 businesses: A and B.

A is a "capital heavy" business -- like a telecom operator. It needs $20 in assets to produce $1 of annual earnings.

B is a "capital light" business -- like a software company. It needs only $2 worth of assets to earn $1 annually.

5/

From the standpoint of an *owner*, B is likely to look like a better business than A.

For example, suppose we're owners who have $100K of capital to invest.

Which business should we put our $100K into?

A or B?

From the standpoint of an *owner*, B is likely to look like a better business than A.

For example, suppose we're owners who have $100K of capital to invest.

Which business should we put our $100K into?

A or B?

6/

Option 1.

We put our $100K into A.

We use it to buy $100K worth of telecom assets -- routing equipment, switches, towers, whatever.

These assets will earn us $5K per year.

Because A's "Return Ratio" is $1/$20, or 5% per year.

Option 1.

We put our $100K into A.

We use it to buy $100K worth of telecom assets -- routing equipment, switches, towers, whatever.

These assets will earn us $5K per year.

Because A's "Return Ratio" is $1/$20, or 5% per year.

7/

Option 2.

We put our $100K into B.

We pay a developer $100K to build new software for the company.

And we sell this software to earn $50K per year.

Because B's "Return Ratio" is $1/$2, or 50% per year.

Option 2.

We put our $100K into B.

We pay a developer $100K to build new software for the company.

And we sell this software to earn $50K per year.

Because B's "Return Ratio" is $1/$2, or 50% per year.

8/

This looks like a no-brainer.

For the *same* $100K we PUT IN, we get to TAKE OUT only $5K/year from A, but $50K/year from B.

A is like a savings account that pays us 5% interest. B, on the other hand, pays us 50% interest.

Clearly, B wins.

This looks like a no-brainer.

For the *same* $100K we PUT IN, we get to TAKE OUT only $5K/year from A, but $50K/year from B.

A is like a savings account that pays us 5% interest. B, on the other hand, pays us 50% interest.

Clearly, B wins.

9/

Thus, HIGHER Return Ratios correspond to BETTER businesses. Owners of such businesses get more "bang for their buck".

Return Ratios generally have 2 parts:

The Numerator = how much cash can be TAKEN OUT each year, and

The Denominator = how much cash was PUT IN.

Thus, HIGHER Return Ratios correspond to BETTER businesses. Owners of such businesses get more "bang for their buck".

Return Ratios generally have 2 parts:

The Numerator = how much cash can be TAKEN OUT each year, and

The Denominator = how much cash was PUT IN.

10/

But our example above -- the telecom company vs the software company -- was rather simplistic.

To arrive at our Return Ratio, we just took the annual *earnings* of each company, and divided that by the *assets* of the company.

This is called ROA: Return On Assets.

But our example above -- the telecom company vs the software company -- was rather simplistic.

To arrive at our Return Ratio, we just took the annual *earnings* of each company, and divided that by the *assets* of the company.

This is called ROA: Return On Assets.

11/

There are a few problems with ROA.

For one thing, telecom companies (unlike software companies) usually employ a LOT of debt.

They may earn only 5% on *assets*. But most of these assets may have been bought with *borrowed* money.

Not *owner's* money.

There are a few problems with ROA.

For one thing, telecom companies (unlike software companies) usually employ a LOT of debt.

They may earn only 5% on *assets*. But most of these assets may have been bought with *borrowed* money.

Not *owner's* money.

12/

This *leverage* can significantly improve the return realized by an owner.

For example, if we assume that our $100K of "owner's money" is combined with $400K of *debt* at 2% interest, then our Return Ratio jumps from 5% to 17% per year.

For more:

This *leverage* can significantly improve the return realized by an owner.

For example, if we assume that our $100K of "owner's money" is combined with $400K of *debt* at 2% interest, then our Return Ratio jumps from 5% to 17% per year.

For more:

https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1380942728222011395

13/

This 17% is called Return On Equity (ROE).

It reflects that not ALL capital used by a business has to come from its *owners*.

Only the *equity* portion comes from owners.

When *non-equity* sources of capital (eg, debt) are large, ROE can meaningfully exceed ROA.

This 17% is called Return On Equity (ROE).

It reflects that not ALL capital used by a business has to come from its *owners*.

Only the *equity* portion comes from owners.

When *non-equity* sources of capital (eg, debt) are large, ROE can meaningfully exceed ROA.

14/

Besides debt, there are many other sources of non-equity capital that businesses tap into.

All these sources serve to increase ROE over ROA.

That's because the "denominator" for ROA is ALL assets. But for ROE, it's just the *EQUITY portion* of those assets.

Besides debt, there are many other sources of non-equity capital that businesses tap into.

All these sources serve to increase ROE over ROA.

That's because the "denominator" for ROA is ALL assets. But for ROE, it's just the *EQUITY portion* of those assets.

15/

In addition to these 2 denominators (Assets for ROA and Equity for ROE), some other "flavors" are also popular.

For example, some people like to exclude surplus cash from the denominator. The logic is that this cash is not really needed for the business to run.

In addition to these 2 denominators (Assets for ROA and Equity for ROE), some other "flavors" are also popular.

For example, some people like to exclude surplus cash from the denominator. The logic is that this cash is not really needed for the business to run.

16/

Surplus cash *could* be dividended out to owners any time.

But the managers are holding on to it, hoping that they will get an opportunity sooner or later to invest it somewhere attractive.

Google, Facebook, and Berkshire Hathaway are examples of such businesses.

Surplus cash *could* be dividended out to owners any time.

But the managers are holding on to it, hoping that they will get an opportunity sooner or later to invest it somewhere attractive.

Google, Facebook, and Berkshire Hathaway are examples of such businesses.

17/

When such "surplus cash" is excluded, Return Ratios immediately look better.

This is part of a broader distinction between "capital that has already been productively deployed" (ROIC) vs "all capital held in the business, whether productively deployed or not" (ROCE).

When such "surplus cash" is excluded, Return Ratios immediately look better.

This is part of a broader distinction between "capital that has already been productively deployed" (ROIC) vs "all capital held in the business, whether productively deployed or not" (ROCE).

18/

And just like the *denominator*, there are many *numerator* flavors as well.

Some people like to use reported earnings. Some like EBIT. Some prefer owner earnings. Others use FCF.

Each gives rise to a different Return Ratio.

Like snowflakes, no two of them are the same.

And just like the *denominator*, there are many *numerator* flavors as well.

Some people like to use reported earnings. Some like EBIT. Some prefer owner earnings. Others use FCF.

Each gives rise to a different Return Ratio.

Like snowflakes, no two of them are the same.

20/

Given that we have so many Return Ratio variants, a natural question to ask is: which is the best?

Which one should we use for our analyses?

The answer is: it depends on the situation.

Some ratios work better in some situations. Others work better in other situations.

Given that we have so many Return Ratio variants, a natural question to ask is: which is the best?

Which one should we use for our analyses?

The answer is: it depends on the situation.

Some ratios work better in some situations. Others work better in other situations.

21/

Let's take an example to see this.

Which is better: return on ALL capital or ONLY on *tangible* capital (ie, excluding goodwill/intangibles)?

Suppose XYZ Inc. has $1M of tangible capital, and earns $250K/year on that capital. That's a 25% return.

Let's take an example to see this.

Which is better: return on ALL capital or ONLY on *tangible* capital (ie, excluding goodwill/intangibles)?

Suppose XYZ Inc. has $1M of tangible capital, and earns $250K/year on that capital. That's a 25% return.

22/

Now, suppose we *buy* XYZ for $5M.

In this case, even though *XYZ* earns 25% on *its* capital, *we* won't earn 25% on *our* capital.

Why? Because we bought XYZ at a *premium*.

Now, suppose we *buy* XYZ for $5M.

In this case, even though *XYZ* earns 25% on *its* capital, *we* won't earn 25% on *our* capital.

Why? Because we bought XYZ at a *premium*.

23/

*After* buying XYZ, we'll have $1M of tangible capital.

Plus, we'll have $4M of "goodwill" (the premium we paid over tangible capital to acquire XYZ).

So, which of these Return Ratios is "better"?

Return on ONLY tangible capital = 25%, OR

Return on ALL capital = 5%?

*After* buying XYZ, we'll have $1M of tangible capital.

Plus, we'll have $4M of "goodwill" (the premium we paid over tangible capital to acquire XYZ).

So, which of these Return Ratios is "better"?

Return on ONLY tangible capital = 25%, OR

Return on ALL capital = 5%?

24/

The answer depends on what we're going to DO with XYZ in the future.

We could just TAKE OUT the $250K it makes in earnings each year.

And we'll earn 5% on our $5M purchase price.

In this case, "Return on ALL Capital" represents our situation better.

The answer depends on what we're going to DO with XYZ in the future.

We could just TAKE OUT the $250K it makes in earnings each year.

And we'll earn 5% on our $5M purchase price.

In this case, "Return on ALL Capital" represents our situation better.

25/

OR, if XYZ's business allows it, we could RE-INVEST XYZ's earnings back into itself each year -- to GROW these earnings over time.

Suppose we do this for 40 years.

And suppose XYZ is able to earn 25%/year on all re-invested capital as well.

OR, if XYZ's business allows it, we could RE-INVEST XYZ's earnings back into itself each year -- to GROW these earnings over time.

Suppose we do this for 40 years.

And suppose XYZ is able to earn 25%/year on all re-invested capital as well.

26/

In that case, XYZ's earnings will GROW at 25% per year.

In Year 1, XYZ will earn $250K.

In Year 41, it will earn $250K * (1.25^40) ~= $1.88B!

Suppose we TAKE OUT this ~$1.88B every year starting at the end of Year 41.

On our $5M purchase price, that's a ~20.65% return.

In that case, XYZ's earnings will GROW at 25% per year.

In Year 1, XYZ will earn $250K.

In Year 41, it will earn $250K * (1.25^40) ~= $1.88B!

Suppose we TAKE OUT this ~$1.88B every year starting at the end of Year 41.

On our $5M purchase price, that's a ~20.65% return.

27/

So, IF we're able to *re-invest* earnings at the *same* Return Ratio for a long time, "Return on ONLY Tangible Capital (= 25%)" represents our situation much better.

That's the moral of the story: different Return Ratios for different situations.

So, IF we're able to *re-invest* earnings at the *same* Return Ratio for a long time, "Return on ONLY Tangible Capital (= 25%)" represents our situation much better.

That's the moral of the story: different Return Ratios for different situations.

28/

Thus, Return on Tangible vs ALL Capital is the distinction between what's earned by a *business* vs *its owner*.

And IF the business allows *re-investment* at similar *incremental* returns, this distinction matters less and less over time.

For more:

Thus, Return on Tangible vs ALL Capital is the distinction between what's earned by a *business* vs *its owner*.

And IF the business allows *re-investment* at similar *incremental* returns, this distinction matters less and less over time.

For more:

https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1399083401697628162

29/

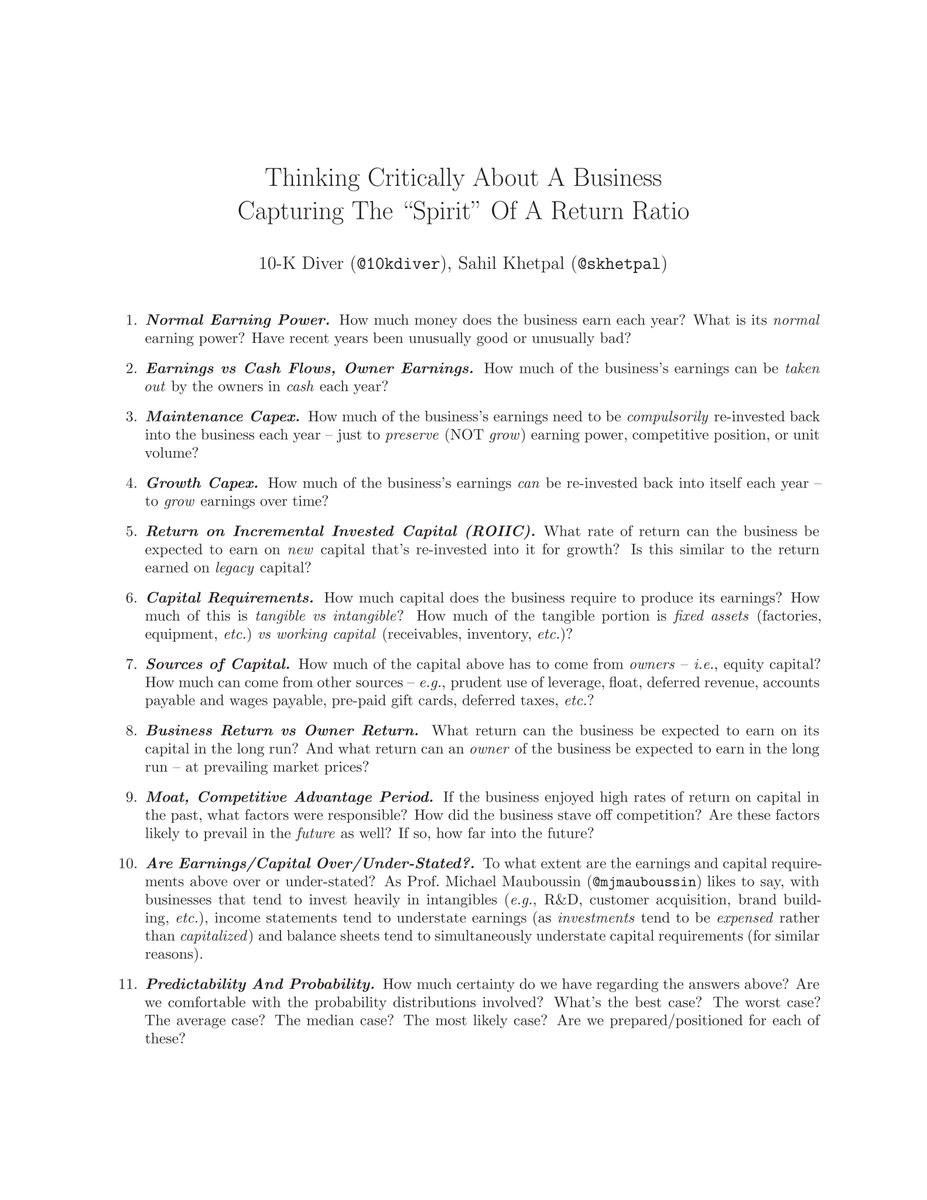

As Charlie Munger likes to say, people *calculate* too much and *think* too little.

This is true for Return Ratios.

*Calculating* a bunch of ratios is NO substitute for *thinking* critically about a business.

So, here's a checklist to help you with this *thinking*:

As Charlie Munger likes to say, people *calculate* too much and *think* too little.

This is true for Return Ratios.

*Calculating* a bunch of ratios is NO substitute for *thinking* critically about a business.

So, here's a checklist to help you with this *thinking*:

30/

For more on judging business quality, I recommend reading this wonderful section from Buffett's 2007 letter -- "Businesses: The Great, The Good, And The Gruesome":

For more on judging business quality, I recommend reading this wonderful section from Buffett's 2007 letter -- "Businesses: The Great, The Good, And The Gruesome":

31/

Please join Sahil and me tomorrow (Sun, 2021-Dec-19) at 1pm ET, for a new episode of Money Concepts via Callin.

We'll discuss Return Ratios and more. Hope to see you there!

Note: We changed the time from 4pm ET to 1pm ET to accommodate more people.

callin.com/?link=LFCJbQhQ…

Please join Sahil and me tomorrow (Sun, 2021-Dec-19) at 1pm ET, for a new episode of Money Concepts via Callin.

We'll discuss Return Ratios and more. Hope to see you there!

Note: We changed the time from 4pm ET to 1pm ET to accommodate more people.

callin.com/?link=LFCJbQhQ…

32/

Sahil is the CEO (and a founder) of TIKR (@theTIKR) -- a wonderful tool for researching stocks.

Sahil has a simple mission: to give little guys the power of a Bloomberg Terminal.

If you can, please support him. Sign up for TIKR Pro here:

tikr.com/10kdiver

Sahil is the CEO (and a founder) of TIKR (@theTIKR) -- a wonderful tool for researching stocks.

Sahil has a simple mission: to give little guys the power of a Bloomberg Terminal.

If you can, please support him. Sign up for TIKR Pro here:

tikr.com/10kdiver

33/

If you're still with us, thank you very much!

We hope this thread helped you think more clearly about Return Ratios and related topics.

Please stay safe. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

If you're still with us, thank you very much!

We hope this thread helped you think more clearly about Return Ratios and related topics.

Please stay safe. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

My apologies. The image in Tweet 29 is transparent -- which makes it difficult to read on some devices.

Here's a non-transparent version of the same image:

Here's a non-transparent version of the same image:

For more on how to use TIKR to calculate some of these Return Ratios:

https://twitter.com/skhetpal/status/1473721505943011332

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh