Today in pulp I look back at the publishing phenomenon of gamebooks: novels in which YOU are the hero!

A pencil and dice may be required for this thread...

A pencil and dice may be required for this thread...

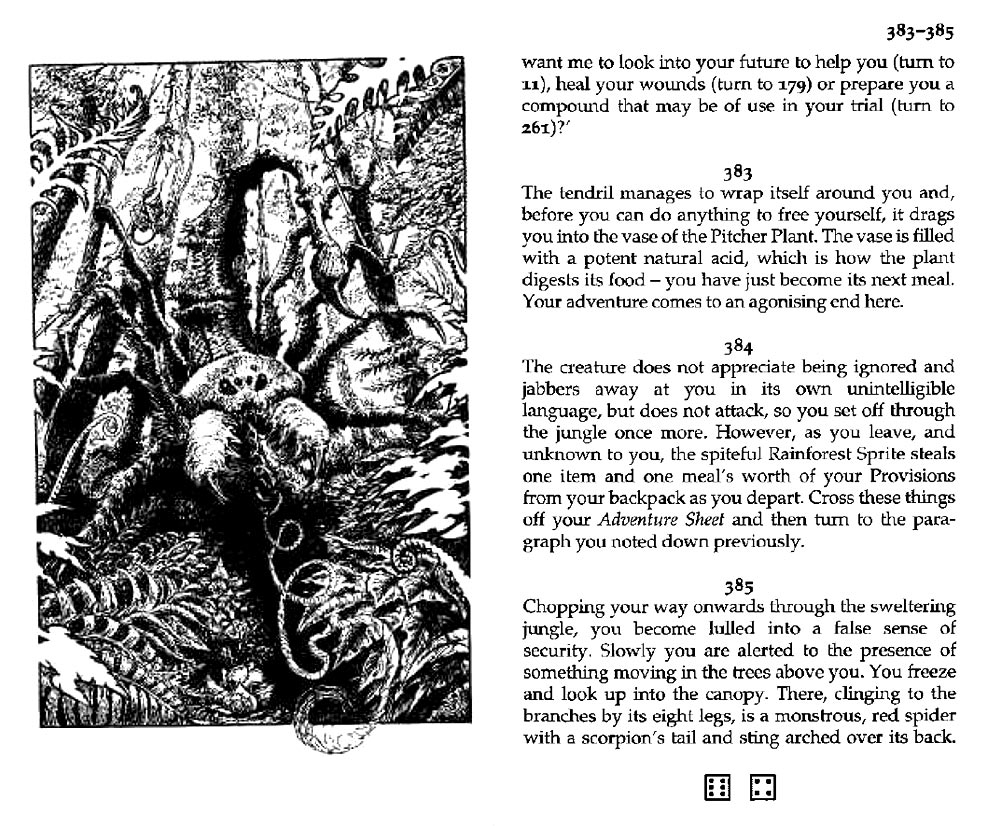

Gamebooks are a simple but addictive concept: you control the narrative. At the end of each section of the story you are offered a choice of outcomes, and based on that you turn to the page indicated to see what happens next.

Gamebook plots are in fact complicated decision tree maps: one or more branches end in success, but many more end in failure! It's down to you to decide which path to tread.

There are many types of gamebook: some are straightforward branching narratives, others ask you to construct a character and use dice to calculate the outcome of combat choices. But they are all (usually) solo adventures - no Dungeon Master is required.

Gamebooks are normally written in the second person: YOU are the hero, and the branching plot is described from your point of view. It's a hard narrative voice to get right.

Gamebooks started to appear in the 1960s: State of Emergency by Dennis Guerrier and Joan Richards (1969) used the cover to explain the concept to bemused readers.

The Tracker Books series began in 1972. Written by Kenneth James and John Allen these were aimed at a young adult audience and featured mystery, detective or quest plots. Most gamebooks tended to focus on a YA audience.

The popularity of Dungeons and Dragons was of course a natural fit for gamebooks. Buffalo Castle (1975) launched the Tunnels and Trolls gamebook system - written especially for solo players but with similar game mechanics to D&D.

But the big breakthrough for gamebooks came in 1976 with the publication of Sugarcane Island by Edward Packard - the first book in the highly successful 'Adventures Of You' series from Pocket Books.

Following the success of Sugarcane Island, Pocket Books rebranded the series as 'Choose Your Own Adventure' and a publishing juggernaut was born!

Choose Your Own Adventure books covered a wide range of genres and had some very clever ideas thrown in as well: for example You Are A Shark is a gamebook based on reincarnation.

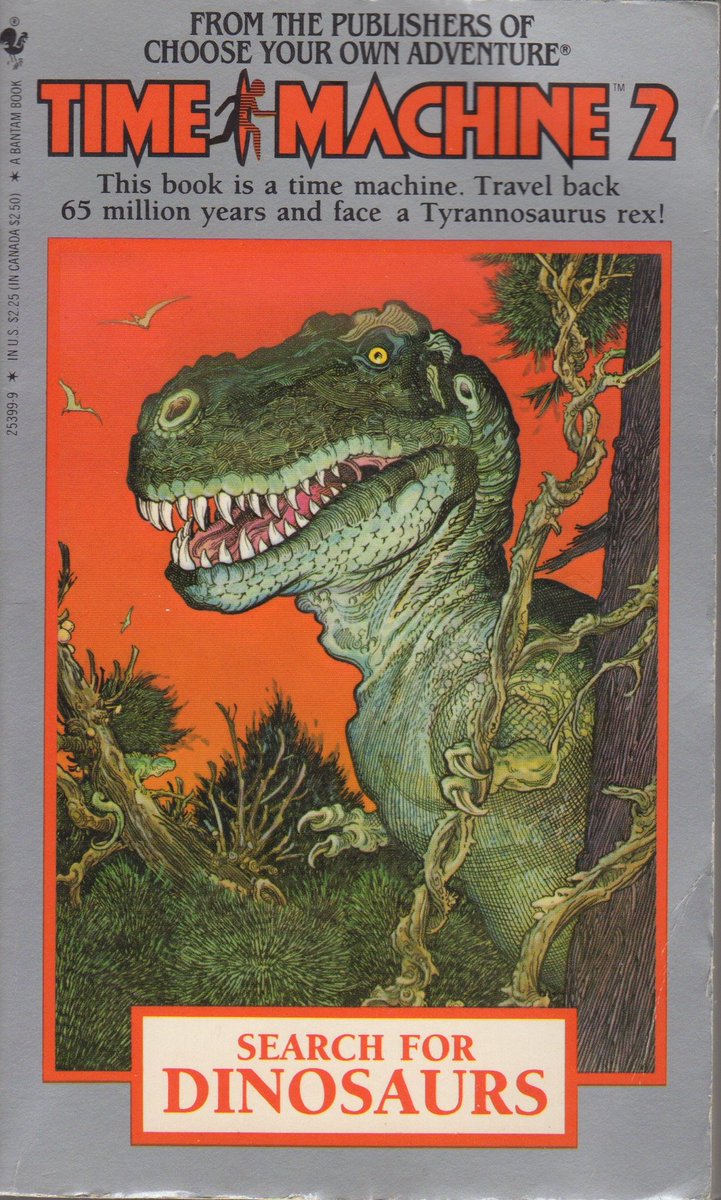

Later owned by Bantam Books, the Choose Your Own Adventure range expanded to cover gamebooks for younger readers. The Time Machine series used the branching plot device in a historical setting - thus cramming some educational history into the kids.

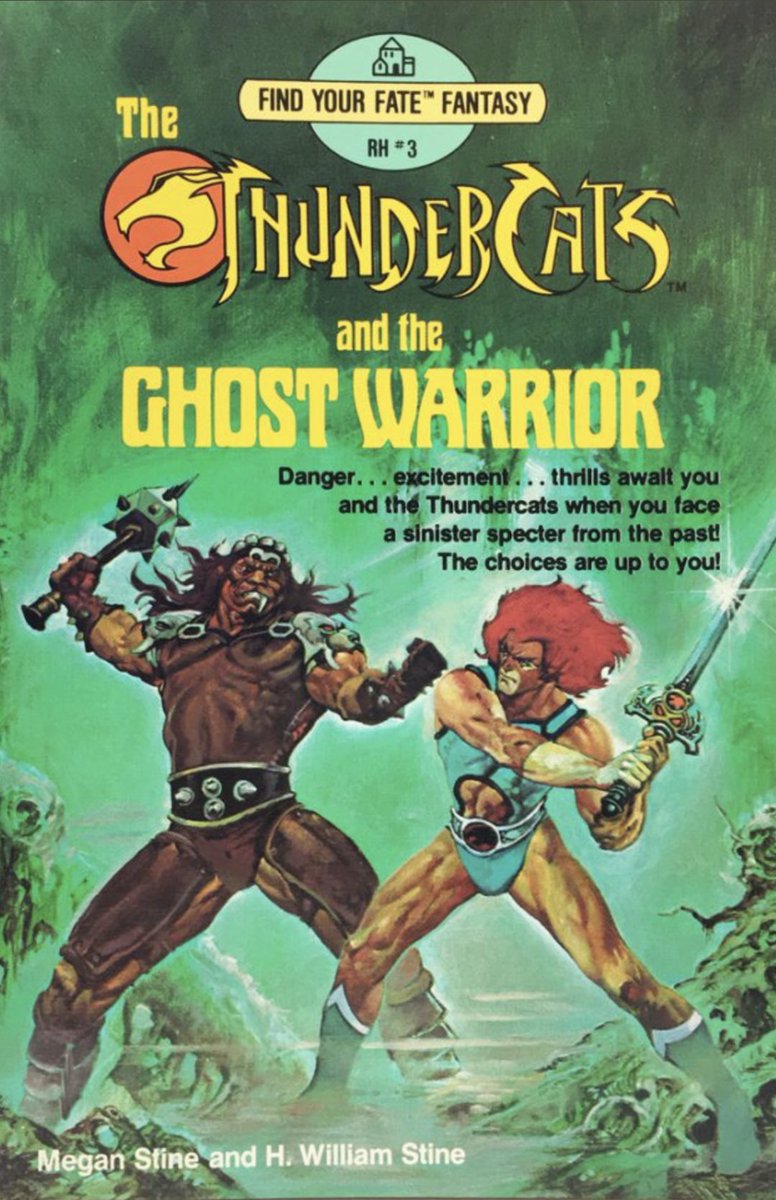

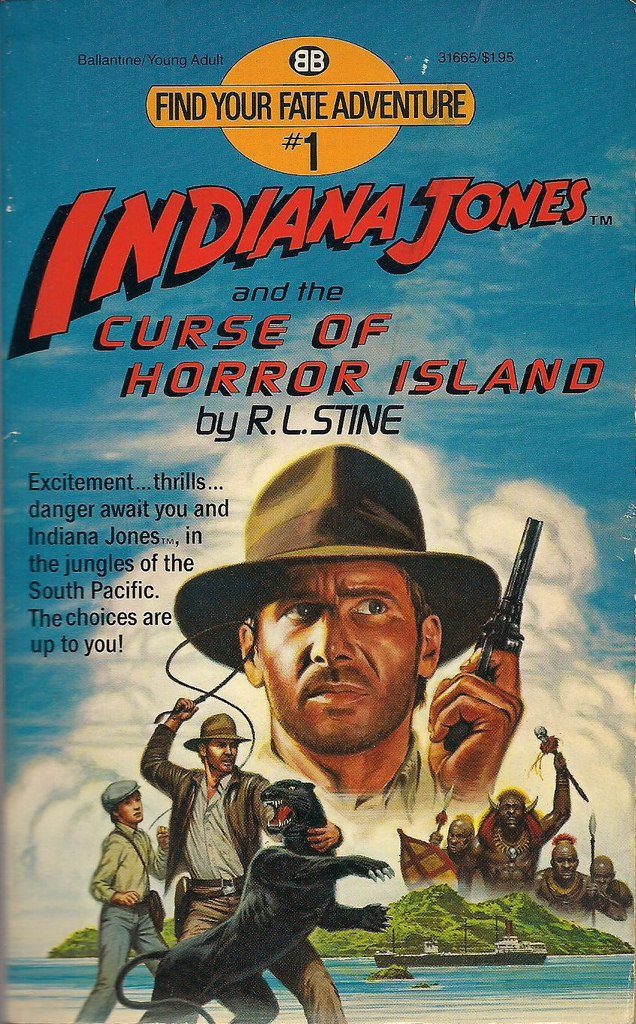

Never one to miss a trick, Ballantine launched their own range of gamebooks in the early 1980s, with the catchy-titled series title Find Your Fate!

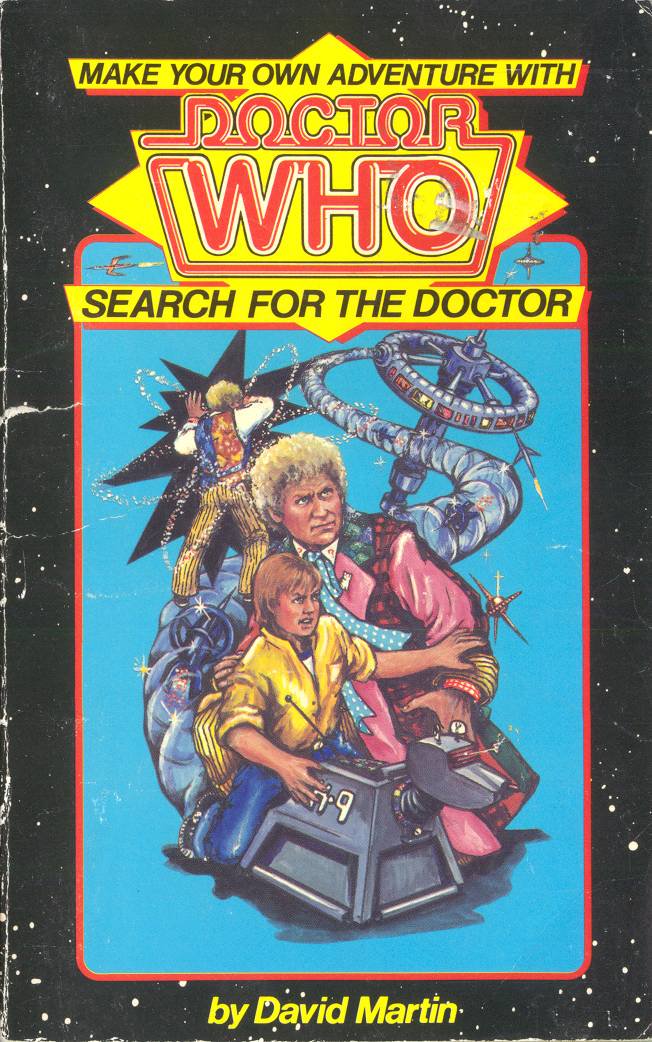

Ballantine also bought the gamebook rights to many popular films and shows: by the mid-80s YOU could be Indiana Jones, James Bond, GI Joe or Doctor Who.

TSR were a little late to the gamebook scene but made up for it with their Endless Quest books, cashing in on the Dungeons & Dragons brand to promote the series.

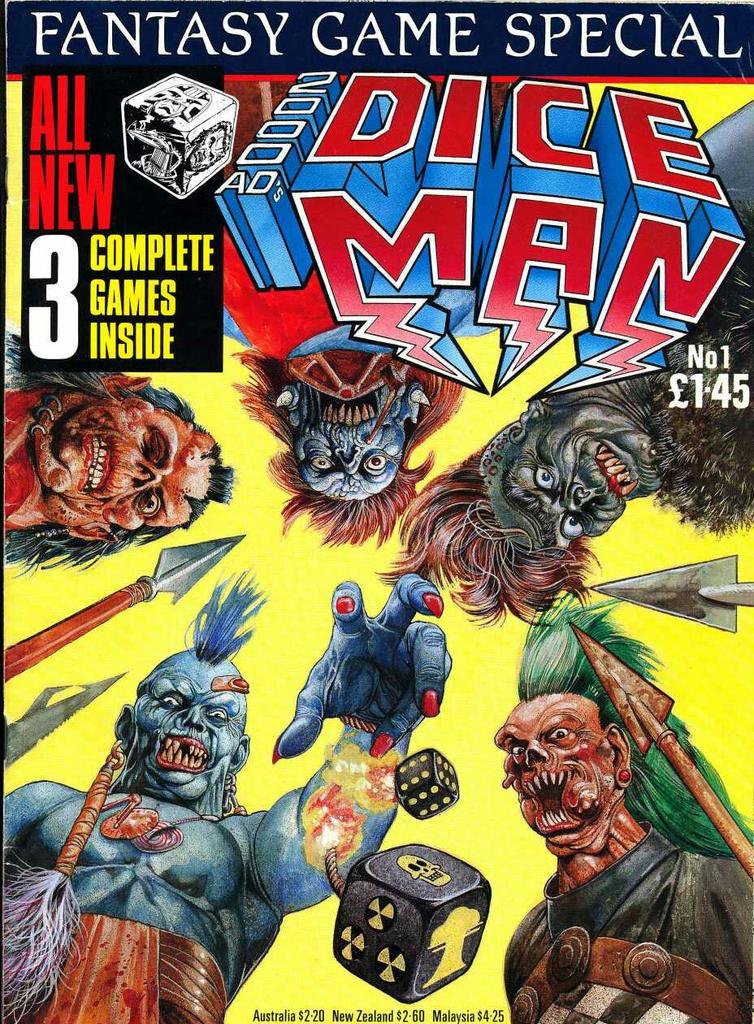

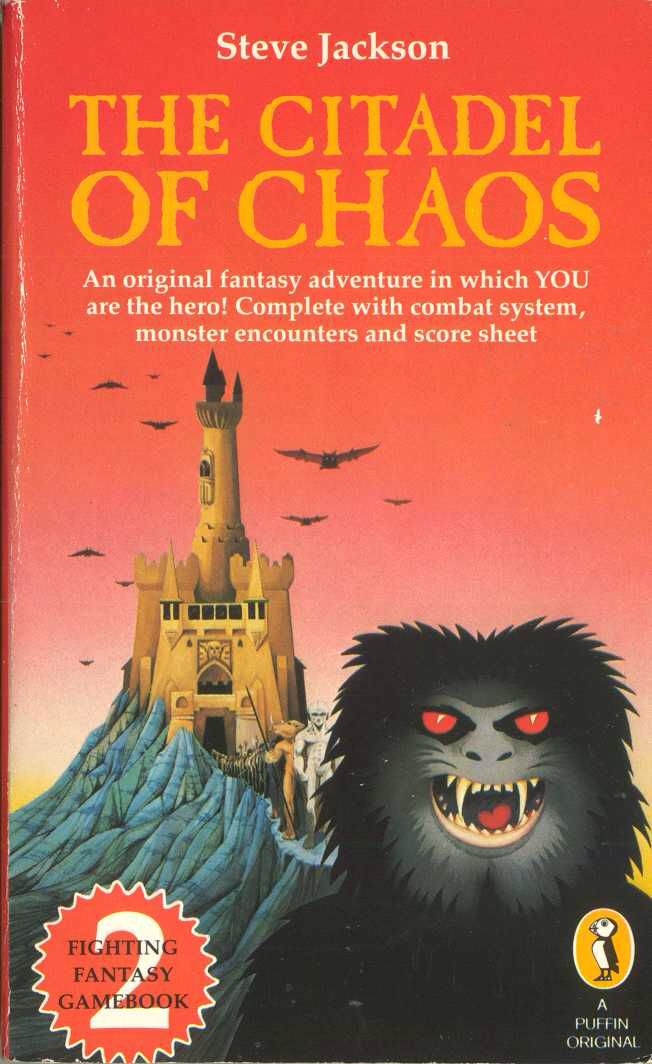

Another hugely important gamebooks line launched in 1982: The Warlock of Firetop Mountain by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone kicked off the Fighting Fantasy series, which blended role-playing game mechanics and branching plot storylines.

Oh the Maze of Zagor...

Oh the Maze of Zagor...

By 1984 the Fighting Fantasy series had its own magazine - Warlock - and it wasn't long before a full role playing game version was launched.

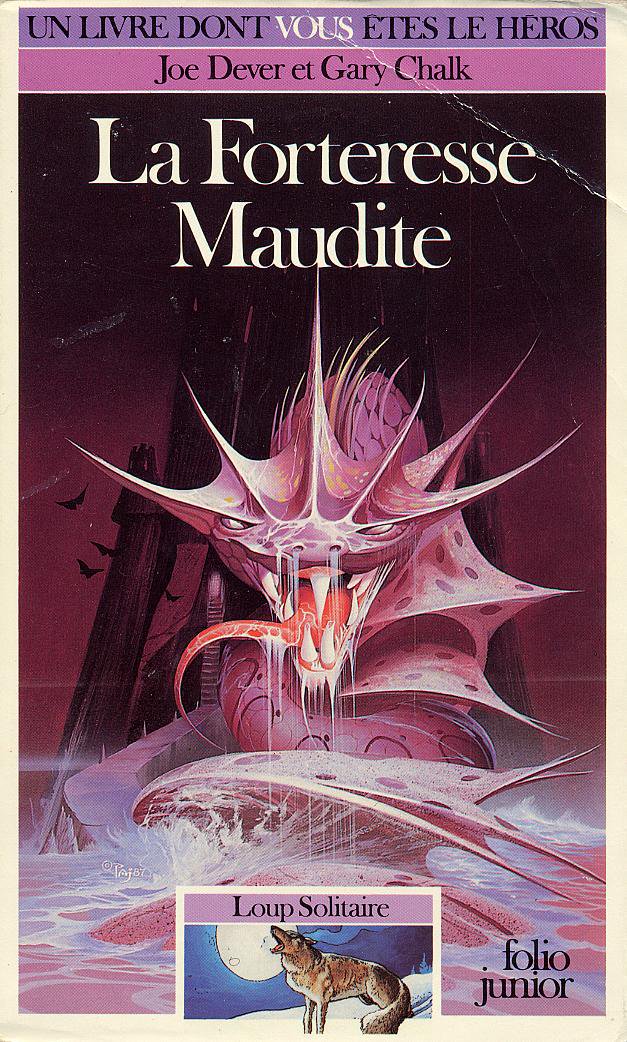

Gamebooks had international appeal and were written in (or translates into) many languages. Joe Denver's Lone Wolf series became Loup Solitaire in France - and was hugely successful.

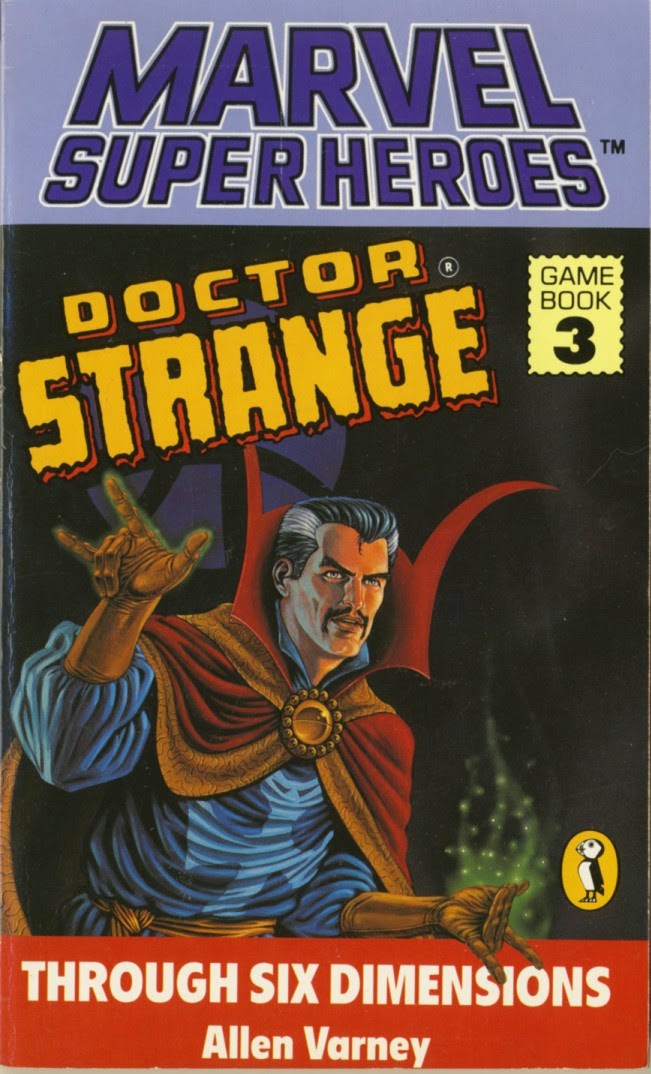

By the late 1980s it seemed every publisher was trying to cash in on gamebooks. Alas the market could only take so much, and soon the games console took over from the Choose Your Own Adventure book as the preferred way to spend a Sunday afternoon.

Some gamebooks were of course very difficult, if not bloody annoying. Many people to this day maintain that it was impossible to win at Starship Traveller. Branched storytelling is an art, and sometimes it doesn't always pan out as intended on the page.

That said, if you have some gamebooks up in your loft do dig them out and give them a re-read. They still have the magic!

For many people gamebooks were a huge part of growing up and a powerful tool for firing their young imagination: happy days indeed. Gamebooks - Twitter salutes YOU!

More stories another time. Right now I have a Citadel of Chaos to conquer...

More stories another time. Right now I have a Citadel of Chaos to conquer...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh