Inspired by this tweet, here's a seasonal 🧵 about colonialism, trade, luxury goods, the Sun King, and the man who invented European cuisine:

https://twitter.com/DrMichaelReeve/status/1471138996562677763

Those highly-spiced, sweet-sour flavours we associate with "Christmas foods" in European cultures have always struck me as a weird anomaly.

Mostly, European cooking uses minimal spices and avoids mixing the sweet and the savoury.

That's a stark contrast to most other cuisines.

Mostly, European cooking uses minimal spices and avoids mixing the sweet and the savoury.

That's a stark contrast to most other cuisines.

I used to think this was just because spices from the tropics weren't much available in Europe, so only got used for special occasions, whereas in places like India they were ubiquitous and thus widely used.

In truth, I think the explanation is close to the opposite.

In truth, I think the explanation is close to the opposite.

You can see this if you look back at medieval European cuisine, which was highly spiced, mixed the sweet and savory constantly, and in many ways resembles "Christmas cooking".

Take the banquet for the coronation of Richard III of England in 1483:

nerdalicious.com.au/history/the-co…

Take the banquet for the coronation of Richard III of England in 1483:

nerdalicious.com.au/history/the-co…

This was as highly-spiced as any Indian, Chinese or Jamaican meal. Pound upon pound of ginger, saffron, cloves, rice, sugar. Sweet dishes presented at the same time as the savoury courses, and sugar mixed into the savoury dishes.

What's more, there's the question of *where* all those spices in non-European cuisines came from. Look at the range of locations in that tweet quoted at the top of this thread. Even India and Indonesia didn't grow all these spices domestically.

How did Jamaican allspice and Mexican chiles make their way into Indian cooking? How did Indonesian nutmeg and cloves get to the same places? Through the spice trade of course.

But who, famously, controlled the spice trade in the early modern period?

European colonial powers — the same nations that, until my lifetime, largely excluded those same ingredients from their own cuisines.

They refused to get high on their own supply.

That's weird, right?

European colonial powers — the same nations that, until my lifetime, largely excluded those same ingredients from their own cuisines.

They refused to get high on their own supply.

That's weird, right?

I think this is largely down to the influence of one man, François Pierre La Varenne, the most influential chef of the 17th century and I'd argue, history.

La Varenne was the chief cook to several prominent aristocrats in the mid-17th century, at the time when Louis XIV, the Sun King, was building up the status of France (and Paris as its capital) as a center of wealth and splendour that would set an example to the rest of Europe.

It's easy to forget now how *anomalous* France is among European nations, but that was very visible in this era.

It was the most populous nation in the world after Ming/Qing China and Mughal India, with an endowment of fertile land far beyond any other European power.

It was the most populous nation in the world after Ming/Qing China and Mughal India, with an endowment of fertile land far beyond any other European power.

It was also singularly unsuccessful at Empire. Until the colonization of west and central Africa in the late 19th century France had never managed to match the colonial successes of smaller, poorer nations like Spain, Portugal, England and the Netherlands.

Louis XIV's powerful first minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert had an idea for how these qualities could be turned to his advantage: build up France as a centre for producing luxury goods like fabric, exporting to other nations to bring in foreign coin for the royal treasury.

Another thing that was happening in this era was that Paris was growing into the largest city in Europe, drawn by the wealth of Louis XIV's court.

With half a million people, only London could compare to it among western European cities.

With half a million people, only London could compare to it among western European cities.

This posed some profound logistical problems.

Cities of that size need a vast surrounding infrastructure to provide them with food, fuel and materials, but the Seine is not a very good trade artery.

It drops just 35 metres over the 450 kilometres between Paris and the sea.

Cities of that size need a vast surrounding infrastructure to provide them with food, fuel and materials, but the Seine is not a very good trade artery.

It drops just 35 metres over the 450 kilometres between Paris and the sea.

Until the river was dredged and railways crossed the land in the 19th century, barges still often needed to be dragged over the shallow shoals downriver from Paris, and in Paris itself you could wade across parts of the river.

Quite a contrast to the Thames, which could float the largest oceangoing vessels of this era direct into the port of London on the daily high tides.

So what is the revolution La Varenne carried out in European cookery?

First, spices are minimized and banished to the dessert course. Spices had to be bought from the Dutch and the English, so represented a loss to the royal treasury under Colbert's mercantilist economics.

First, spices are minimized and banished to the dessert course. Spices had to be bought from the Dutch and the English, so represented a loss to the royal treasury under Colbert's mercantilist economics.

The same goes for sugar, controlled in this era by the Portuguese and Spanish colonies in the Americas.

(Saint-Domingue, the brutally wealthy French sugar colony that later became Haiti, was barely established in this era).

(Saint-Domingue, the brutally wealthy French sugar colony that later became Haiti, was barely established in this era).

There's another reason for banishing spices and sugar in an aristocratic cuisine: They're *cheap*.

European dominance of ocean trade meant that the price of such delicacies was far below what it had been in the middle ages, when they were status-symbol bling.

European dominance of ocean trade meant that the price of such delicacies was far below what it had been in the middle ages, when they were status-symbol bling.

What's expensive in a Paris straining at the carrying capacity and transport networks of the Seine basin?

Fresh, local produce, delicately cooked to bring out its flavour and show off its quality.

Fresh, local produce, delicately cooked to bring out its flavour and show off its quality.

One of La Varenne's most famous creations is duxelles, that paste of mushrooms, herbs, shallots and butter that you find inside the crust of a Beef Wellington, named after his employer, the Marquis d'Uxelles.

To this day fresh mushrooms are hard to transport. In mid-17th century Paris they'd have been an impossible luxury.

La Varenne's was the first European recipe book to include a section on vegetables. I think this isn't because they were humble, but because they were fancy.

La Varenne's was the first European recipe book to include a section on vegetables. I think this isn't because they were humble, but because they were fancy.

Getting vegetables in a good condition on a Parisian dining table in 1650 meant either that you had a fully-functioning kitchen garden amidst some of the costliest real estate in Europe, or you had access to the best transport money could buy.

Colbert's policy of building up France's luxury goods industry was a victim of its own success.

The 1685 anti-Protestant revocation of the edict of Nantes drove many of the country's most skilled artisans into exile, spreading French knowhow and fashion across Europe.

The 1685 anti-Protestant revocation of the edict of Nantes drove many of the country's most skilled artisans into exile, spreading French knowhow and fashion across Europe.

The food fashions of a few Parisian aristocrats from the mid-17th century thus set an enduring template for the whole of Europe.

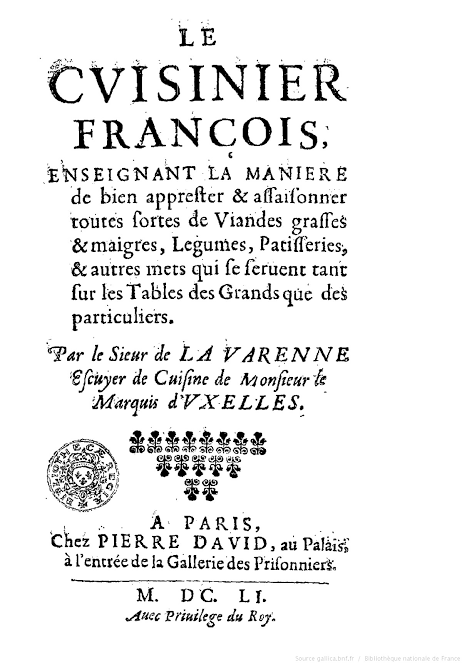

La Varenne's main work, La Cuisinier François, remains in print for nearly 200 years and is pirated across Europe.

La Varenne's main work, La Cuisinier François, remains in print for nearly 200 years and is pirated across Europe.

Original copies are still rare for a reason any cook will recognise: chefs simply used them to death, turning pages with sticky messy fingers until the book fell to bits.

The challenges of France's farm economy and Paris's feeble trade links didn't go away.

Take energy. London was powered from the middle ages with coal ("sea-coal") boated down from Northumbria. Some of the first air pollution laws date from 1285, banning coal-burning in London.

Take energy. London was powered from the middle ages with coal ("sea-coal") boated down from Northumbria. Some of the first air pollution laws date from 1285, banning coal-burning in London.

Amsterdam had peat dug out of its polders to provide energy for warmth and cooking, but Paris had neither.

All its energy was wood from the Morvan forest in the foothills of the Alps, barged down the Seine.

All its energy was wood from the Morvan forest in the foothills of the Alps, barged down the Seine.

For most of the 18th century Paris had been trying to build canals to improve access for the wood barges, but it came too late for Louis XIV's successors.

Wood inflation in the bitter winter of 1788-9, along with the wider inflation that followed, was one reason that the people of Paris were ready for revolution by the summer of 1789.

Even now, France is the only EU country that's self-sufficient in food. And its heavily agricultural economy meant that industrialization was relatively light compared to its neighbours.

We think of France as the home of egalité, but until the 1960s and the European Common Agricultural Policy, its farm-dependent economy led to unusual, almost Latin American-style levels of inequality.

(ends)

Thanks for reading. I like to end the year with a big tweet thread on something non-work related.

If you liked this, here is one from last year about how a ship-eating clam helped spark the Industrial Revolution:

If you liked this, here is one from last year about how a ship-eating clam helped spark the Industrial Revolution:

https://twitter.com/davidfickling/status/1344404814256504832?t=JjR_IDX_8OJrGeIc0VpGvg&s=19

And one from the previous year about why we've never seen evidence of alien civilizations:

https://twitter.com/davidfickling/status/1211028372333056000?t=JjR_IDX_8OJrGeIc0VpGvg&s=19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh