This Day in Labor History: January 1, 1867. Landowner Isham Bailey signed a one-year sharecropping deal with freedmen Cooper Hughs and Charles Roberts. Let's talk about sharecropping, how it was a post-Civil War compromise labor system, and its terrible exploitation!

The point of slavery was to control a labor force. And while we talk about racist violence during and after slavery, the purpose behind that racist violence was to control workers. When the Civil War ended and emancipation came, that did not change.

Too often when we discuss slavery, we beat around the bush as to the real reason it existed--whites expected people of color to labor for them. It was part and parcel of the colonial experiment.

The Black Codes were intended to keep these laborers on the land in a position as close to slavery as possible. When Congress overturned that system and the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, some of the old methods could not be used any longer.

The violence of Reconstruction and its aftermath was not strictly about controlling labor once political rights and demands were on the table, but it still was often about keeping black labor under the thumb of white landowners.

Freed people had concrete demands around their work, largely demanding land of their own to work without white supervision.

But that proved more of a dream than a reality, with northern whites believing as much as southern whites that most black workers should be on plantations laboring for whites.

But none of this meant that freed people were going to allow for the recreation of the slave labor force. Sharecropping became part of the answer because it gave freed people day to day control over their lives, if not their economic destiny.

No more gang labor, as the planters wanted. Landholders tended to split their property into 25-50 acre lots. The landowner would provide the land (of course), a cabin, and credit for supplies.

In exchange, the farmer would pay a percentage of the crop–usually around half–and then also have to pay back debts with the other half.

This particular contract from Bailey to his freedmen provided that they would grow both cotton and corn, handing over slightly more than half of the cotton and two-thirds of the corn.

The Hughs family also had to tend Bailey’s livestock without compensation, but both families received a sizable portion of meat, 550 pounds for Hughs and 487 for Roberts. Maybe the livestock tending was factored into this.

Moreover, Roberts’ wife was hired to do housekeeping for $50 a year. This played into one of black laborers’ biggest desire, which was reproducing Victorian gendered work norms and getting their wives and daughters out of the fields and into their homes.

Don’t underestimate what level of freedom this provided compared to slavery, even if it wasn’t really free labor either.

The National Park Service has a site that is a former plantation in central Louisiana. For some reason, the slave cabins were built of brick instead of wood, so they are still standing. When they were built, the cabins were split into two with at least one family on each side.

Given how overcrowded these cabins tended to be, it could have been more than one family in each. Anyway, sometime after emancipation, those cabins became single-family dwellings.

Someone had taken an axe and chopped a hole in the wall separating the two sides of the cabin. In that hole was the power of emancipation. It might not have been much, but that was a physical symbol of ex-slaves taking control over their lives, or at least as much as they could.

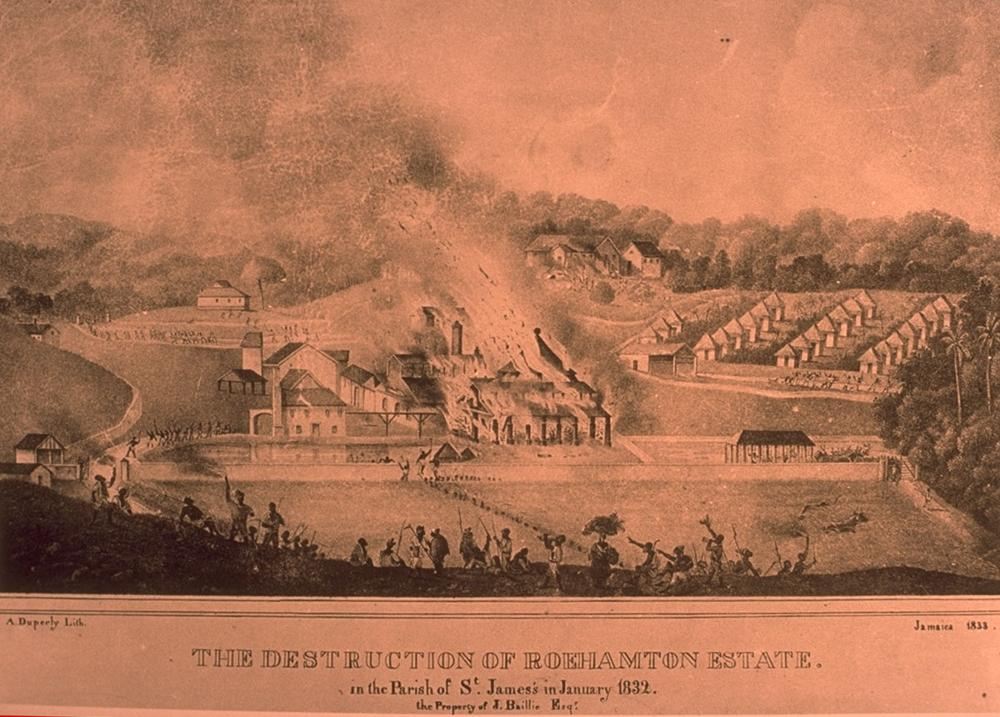

To visualize this a bit, check out this map of a plantation and the quarters for slave laborers versus sharecroppers:

You can see how this undermined white control over black labor and how spreading across the plantation, out of sight of the big house, really mattered to freed slaves.

None of this is to suggest that sharecropping wasn’t exploitative. It was horrible. Most of these farmers were illiterate, despite their desperate and heroic attempts to gain education after the war.

Because many couldn’t read, they were routinely cheated by the landowners and the local merchants. Even if they could read, they were cheated anyway, since the whole system was backed up by the noose and the rifle.

The system expanded over time, sucking white farmers into it as well, to the point that by the 1930s, when the system declined in the face of agricultural modernization and government policy under the New Deal, it was the organizing principle of the southern rural labor force.

Workers did frequently organize to fight for better rights, all up way up to to the Southern Tenant Farmers Union in 1934 but these attempts were often met with maximum violence, such as what happened to tenant farmer organizer Ralph Gray in Alabama in 1931.

States passed laws making it impossible to sell crops to anyone but the landowner.

High interest rates on loans kept farmers in permanent debt, as did crop failures, which would just deepen the required credit to get through the next year. Here is an oral history from a sharecropper named Henry Blake about it was like:

"After freedom, we worked on shares a while. Then we rented. When we worked on shares, we couldn’t make nothing, just overalls and something to eat. Half went to the other man and you would destroy your half if you weren’t careful......

....A man that didn’t know how to count would always lose. He might lose anyhow. They didn’t give no itemized statement. No, you just had to take their word. They never give you no details. They just say you owe so much......

....No matter how good account you kept, you had to go by their account and now, Brother, I’m tellin‘ you the truth about this. It’s been that way for a long time. You had to take the white man’s work on note, and everything......

.....Anything you wanted, you could git if you were a good hand. You could git anything you wanted as long as you worked. If you didn’t make no money, that’s all right; they would advance you more. But you better not leave him, you better not try to leave and get caught.....

....They’d keep you in debt. They were sharp. Christmas come, you could take up twenty dollar, in somethin’ to eat and much as you wanted in whiskey. You could buy a gallon of whiskey...

....Anything that kept you a slave because he was always right and you were always wrong it there was difference. If there was an argument, he would get mad and there would be a shooting take place."

One can see why hundreds of thousands of people started leaving these farms for northern cities during World War I, beginning the Great Migration.

The specific information about this particular sharecropping contract came from this great Gilder Lehrman site, which so often does fantastic work in producing teachable materials and getting them online.

gilderlehrman.org/history-resour…

gilderlehrman.org/history-resour…

Back tomorrow to discuss the 2006 Sago Coal Mine disaster.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh