The old church of St Matthew's in Lightcliffe, West Yorks is now just a tower. The rest of the church was demolished in 1973, despite our strenuous efforts to save it.

The loss was of historical significance — because this was a building of pioneering Georgian construction.

#🧵

The loss was of historical significance — because this was a building of pioneering Georgian construction.

#🧵

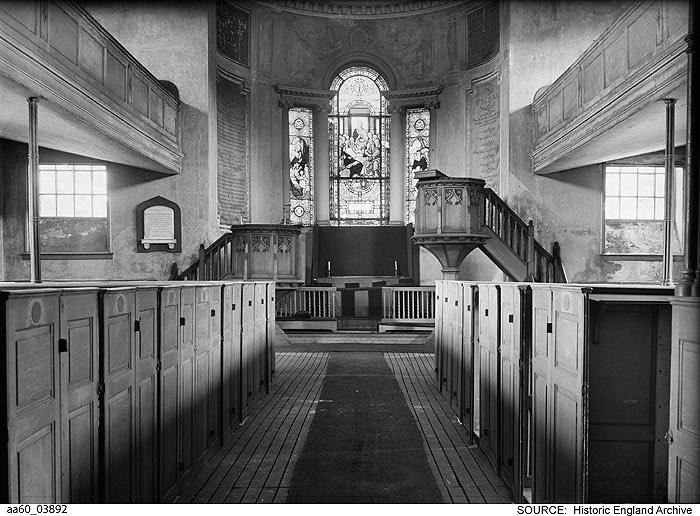

The Neoclassical building had galleries of 'pews with a view' on three sides, and surviving photographs suggest that the quatrefoil columns supporting them were made of cast iron.

2/

2/

The material had been used in buildings since the late 17thC — Christopher Wren employed it in the House of Commons — but the oldest surviving example of cast iron used for gallery supports is at St James's, Toxteth, built in 1775. Lightcliffe's church was built the same year.

3/

3/

Cast iron was far stronger than stone or timber when used in compression — so a cast iron column could be much slimmer than stone but bear the same weight (which must have wowed Lightcliffe's parishioners!)

4/

4/

Just four years after this high-tech solution was employed at St Matthew's, Iron Bridge — the world's first bridge made of cast iron — was built at the Shropshire village of Coalbrookdale, ushering in the English Industrial Revolution.

5/

5/

Although we've lost this innovative example of 18thC engineering, we can still celebrate the achievement of its adventurous builder. He was William Mallinson, Master Mason of Halifax, and his gravestone can be seen in the churchyard, just a few metres from the tower.

6/

6/

Cast iron continued to be used in columns until the turn of the 20thC. However, by the end of the 18thC, wrought iron — more ductile than cast iron — was a booming industry, and that was once again improved upon in the mid 19thC by the production of steel.

8/

8/

You could say that the ground-breaking design of old St Matthew's was a precursor to the steel-framed skyscrapers that tower above our cities today.

9/

9/

So, if you visit Lightcliffe, look up at the tower and spare a thought for William Mallinson, whose use of cast iron in the church there was the start of a journey to building some of the tallest and strongest towers the world has ever seen.

10/10

10/10

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh