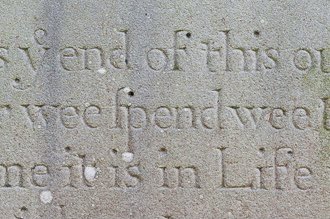

At Llangwm Uchaf, what remains of the gloomy inscription on this crumbling gravestone has a great example of the archaic use of 'ye' (the) which we tweeted about recently, but you can also spot two lovely examples of another extinct letterform: ſ - known as the 'long s'.

At a glance, ſ looks a bit like an f (especially in typefaces that give it a little nub on its left hand side - like in this edition of Paradise Lost).

Long s and short s were both in use, so the epitaph also tells us that if all goes well on earth we can look forward to a 'life of Bliſs' (Bliss).

But why were there two ways of writing the lower case (miniscule) letter s?

But why were there two ways of writing the lower case (miniscule) letter s?

Both forms originated in the Roman period and their use and shape has changed multiple times over the centuries. Ninth century monks writing in the standardised Carolingian script would only use the long s.

But by the 12th century it had become a convention to use the long s at the beginning and in the middle of a word and the short s (which at that time looked like our letter r) at the end. The s we use today was around too but mostly used as the shape for a capital S.

By the 17th century, the rules of when to use a long or short s had become more complex, and weren't always followed consistently. However, one common convention was to use a long and short s for a double s - as in Miſs, congreſs, or Miſsiſsippi.

Thankfully, by the early 19th century, English language printers had almost entirely stopped using the long s, so today we are the Friends of Friendless ... not Friendleſs ... Churches.

However, the long s stuck around (ſtuck around?) for a bit longer in writing made by hand — whether with a pen or a chisel.

That was meant to be the end of our thread but we just couldn’t resist sharing a couple more examples of the long s from our churches. Like this elegant wall monument from Skeffling in the East Riding of Yorks

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh