Kobytev era un artista, scrittore e insegnante, quando i nazisti invasero l'Unione Sovietica divenne un artigliere privato dell'821° reggimento di artiglieria. Ferito in battaglia, fu imprigionato nel campo di concentramento di Khorol dove furono assassinati 90.000 prigionieri.

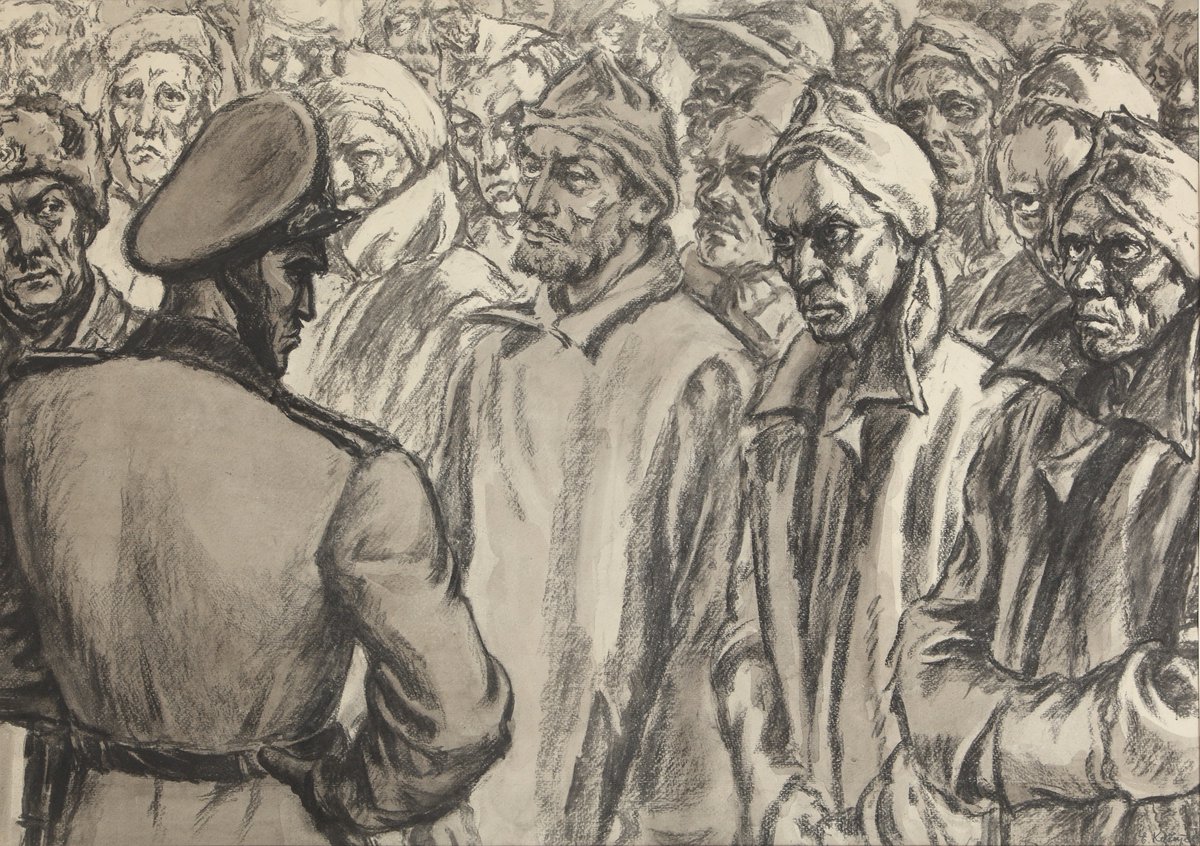

Kobytev riuscì a sopravvivere distraendosi con l'arte: prese appunti e disegnò molti schizzi in cui immortalò la vita nel campo. Quando le guardie scoprirono che cosa stava facendo, iniziarono ad ordinargli di disegnare i loro ritratti.

Le guardie, entusiaste del lavoro svolto dal prigioniero, iniziarono a pagarlo in cibo, cibo di pessima qualità, ma pur sempre cibo extra. Naturalmente i ritratti delle guardie erano molto più lusinghieri di quelli che fece dopo la fine della guerra:

Nel 1943, Kobytev riuscì a fuggire dalla prigionia e si unì nuovamente all’Armata Rossa. Dopo la fine della seconda guerra mondiale gli fu conferita la medaglia come eroe dell’Unione Sovietica per il suo eccellente servizio militare durante le battaglie.

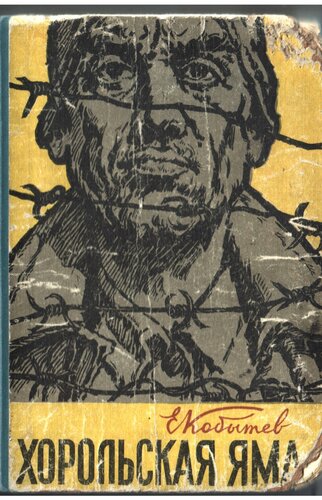

Dopo la guerra diventò un artista e si dedicò all’insegnamento nella scuola d’arte di Krasnojarsk. Nel 1959 creò una serie di dipinti “All’ultimo respiro” sul cameratismo e sul coraggio del popolo sovietico. L'arte lo aiutò e riuscì anche a scrivere un libro sulle sue esperienze.

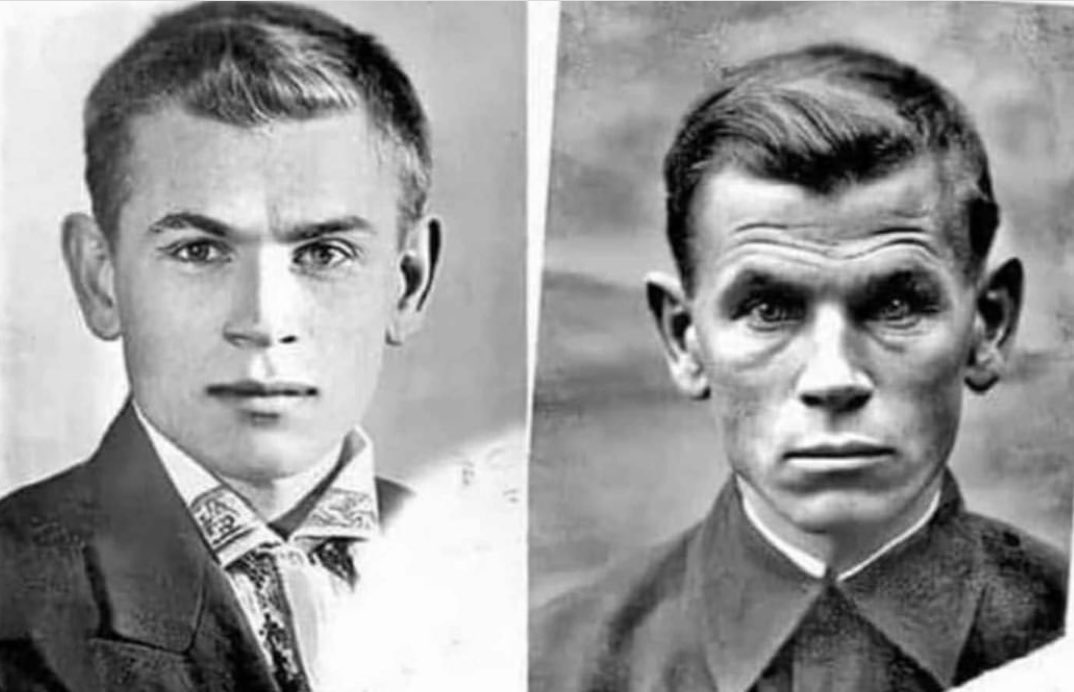

Le prime due foto non mostrano soltanto il volto di un soldato prima e dopo la guerra, bensì prima e dopo gli orrori della guerra e le inimmaginabili sofferenze di un campo di concentramento.

Evgeny Stepanovich Kobytev morì nel 1973, trent’anni dopo essere uscito dall’inferno del campo di Khorol e dopo aver visto, prima di tutto sul proprio volto allo specchio, i devastanti effetti di una guerra disumana.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh